Lucy Jones ’76 stands in front of an elementary school in Pasadena, California, imagining disaster. In her mind’s eye, she sees the roof caving in, the mortar between the red bricks crumbling, the walls collapsing on the kids out front doing cartwheels and on parents greeting their sons and daughters after a day at school. People would be severely injured by debris. Some might die. Whatever was left of the building would perish in flames.

For her honesty and bluntness, she’s earned celebrity status in a city of celebrities. Magazines call her the “Earthquake Lady.” Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti recently said she’s “the face of earthquakes in Southern California.” She receives both marriage proposals and hate mail. “Los Angeles is home to many celebrities,” Garcetti notes, “but in our time of greatest need, after an earthquake, there is no greater, smarter, or more popular rock star than Dr. Lucy Jones.”

People are finally beginning to heed Jones’s warnings. Last year, she took on her most public role yet, after Garcetti charged her with devising a plan to make L.A. more earthquake-resilient. The last major Los Angeles earthquake having occurred 300 years ago, the city is overdue for another big one. Such quakes, after all, typically occur every 150 years. As a result, Jones, the mayor’s staff, and three expert panels have proposed the largest public infrastructure program in the city’s history: several billion dollars spent over thirty years to reinforce buildings, fortify power and telecommunications lines, and ensure the continued flow of water. Garcetti has pledged his full support to the plan. If it’s implemented, Jones’s legacy may be to have saved Los Angeles from total destruction.

The earth is not a stable place. Several million earthquakes happen every year, though the vast majority are too weak to attract much notice, or they happen in remote, wild areas or under the oceans. The earth’s tectonic plates are moving all the time, their edges snagging and breaking free, releasing a burst of energy that triggers a quake.

In 2008, Jones, along with a team of more than 300 academics, published “The ShakeOut Scenario,” an exhaustive study of what would happen to L.A. as a result of the inevitable major quake. Their conclusion was that the city would be hit with more than 10,000 landslides, 1,800 fatalities, 50,000 injuries, 1,600 fires, and a $200 billion economic loss.

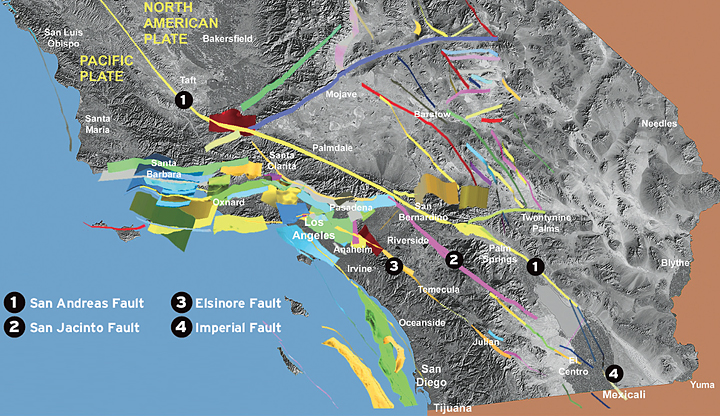

“The ShakeOut Scenario” dug deeper than any previous estimate, looking at such things as how many serious car crashes there would be as people fled the city and how long it would take to repair the thirty-two aqueducts and thirty-nine natural gas and oil pipelines that cross the San Andreas Fault. “It’s not that we’re all going to die,” Jones says. “It’s just that we will be like [post-Hurricane Katrina] New Orleans. No one will want to live here.”

Even “The ShakeOut Scenario” didn’t spur action. Real estate developers balked at the high cost of retrofitting buildings and the increased expense of erecting new ones. The city was unwilling to help. Jones was entering her fifties when she started working on what would eventually become “The ShakeOut Scenario.” Having authored more than ninety scientific papers on earthquakes, she knew that taking action soon was important. “I was thinking, ‘Do I write more scientific papers, or do I get the science used in the real world?’” she says. She chose the latter and eventually became the Earthquake Lady. “The earthquake is inevitable,” she says, “but the disaster isn’t.”

An energetic woman, Jones can talk about earthquakes for literally hours. “She sucks the air out of a room,” but in a good way, says Dale Cox, a colleague at USGS. “She immediately starts engaging with the ideas and has complete enthusiasm for the moment.”

In addition to her post at USGS, Jones is a visiting researcher at the California Institute of Technology. I met with her in November at her office on Caltech’s Pasadena campus. In keeping with her approachable informality, she was dressed in a blue tie-dyed shirt. At the time, she was busy preparing for the public release of her report to Mayor Garcetti on the city’s lack of earthquake preparedness. She said she was exhausted, but it didn’t show.

One of Jones’s first memories is of an earthquake. She was two years old and living in Ventura, just north of Los Angeles. The quake registered 5.2, and her mother took her and her two siblings into a hallway and told them to cover their heads for protection. She then placed herself on top of her children to shield them further. Jones says she remembers the family’s Siamese cat shrieking.

Her father was an aerospace engineer, and, when she was seven, he took her to his office and showed her the computer he was using. It was an early mainframe, a massive machine. He showed her a program that could compute prime numbers more quickly than any other he had seen. “He was so excited with [its] elegance,” Jones recalls. “He was sure his daughter would also enjoy it.”

Although her father encouraged her interest in math and science, her high school guidance counselor told her, “You shouldn’t show you’re good at math, because the boys won’t like you.” Even when she earned a perfect score on a science aptitude test, the counselor assumed she had cheated and made her take the exam again while she watched. Jones’s score was still perfect.

“I was bored out of my mind in high school,” Jones says. She chose to spend her senior year abroad with her aunt and uncle; he worked in Taiwan as a China expert for the U.S government. The Taiwanese turned out to be more encouraging to girls who loved science. Her math teacher spotted her talent immediately. “You are too smart to be in this class,” he told her. “I’m going to teach you separately.” She spent that year doing college-level math.

Before she returned to California, her Taiwanese teacher had another message for her: “It’s your filial responsibility to your family to do as much as you can with the talent you’ve been given.” Several years later, her grandmother agreed: “You’ve got your grandfather’s brains,” she said. “Don’t waste them.” They were the last words she spoke to Jones. She died a week later.

In 1972, Jones was accepted to Radcliffe, which had not yet merged with Harvard. She resented being segregated from men and so chose Brown, where Pembroke and the men’s college had already merged. One of her teachers told her she was making a mistake; she would find a better class of men at Harvard.

At Brown she concentrated in both Chinese and physics. By her sophomore year she was the only female physics concentrator left. “Good afternoon, lady and gentlemen,” her professor would say at the beginning of every class. Jones liked that. “He was glad to have me there,” she says.

Jones recalls that in her sophomore year, at a brunch with geology professor Terry Tullis and several other faculty members, Tullis told her, “Physicists make bombs. Geophysicists get to play in the mountains and get paid for it.” That sounded good. Jones signed up for her first geology class. Tullis, now a professor emeritus of geological sciences, remembers that brunch differently. What he recalls saying is he knew of several physicists who had ultimately found geophysics a more interesting subject. In any case, Tullis says, “I was responsible for getting Lucy into geophysics. That was one of the best contributions to my field I will make in my scientific career.” Jones went on to earn a geophysics PhD at MIT. She was the only woman in the program.

In 1985, now working for the USGS, which is part of the Department of the Interior, Jones published the paper that would make her reputation. No one could—and to this day can’t—predict when an earthquake will strike. Jones wondered whether it would be possible to predict the severity of the tremors that commonly follow an earthquake. Knowing this would help government officials prepare the public.

Over time, journalists began to value her knowledge. While public figures scramble to appear responsible and in charge, Jones offers up scientific facts in an accessible way. “She stands alone in her ability to explain the complicated technological dynamics of earthquakes in a way the average individual can understand,” says Conan Nolan, a reporter and anchor for KNBC-TV in Los Angeles who has covered Jones for several decades. He says Jones has had the same impact on the public’s understanding of earthquakes as Charles Francis Richter, who invented the Richter scale in the early 1930s.

Jones was at work in 1992 when a medium-sized earthquake rattled the desert about 100 miles east of Los Angeles. She briefed emergency-response officials, but, when a second quake followed, she found herself in the dual role of expert and mother. Her husband, Egill Hauksson, an Icelandic-born seismologist at Caltech, had been called on to deal with a high-level computer emergency there. He took with him the couple’s two young children, Sven and Niels, and asked Jones to look after one-year-old Niels while he cared for Sven. She addressed the press with Niels in her arms. “He glowered at the cameras,” she recalls, “but he didn’t scream.”

Throughout her career, Jones had never asked for special treatment because of her gender. Suddenly she became a symbol of maternal comfort during a time of crisis. She became “the earthquake mother,” says KNBC’s Nolan. He says people watching the TV news thought, “It can’t be too bad if she has a child in her arms.” Unexpectedly, she became a feminist icon. Women saw her as a symbol of the working woman who could easily care for her child at the same time. Jones wasn’t so sure. She had felt she wasn’t spending enough time with her children and had in fact been working at the USGS part-time, something she continued to do until 2002, when her children were older.

In January 2014, Mayor Eric Garcetti asked Jones to become the Los Angeles earthquake czar. She was appointed head of the Mayoral Seismic Safety Task Force, a group of city officials and business representatives charged with studying the city’s earthquake readiness and making recommendations to improve it. “She’s the translator between the science and politics,” says David Cocke, a structural engineer who served with Jones on the task force. Jones kept her USGS job and refused to take a salary for her city work. She wanted to make decisions based solely on science and did not want the public to think money or politics could shape her judgment.

The task force’s 126-page report, completed in December, called for drastic changes. Two classes of buildings are particularly vulnerable to earthquake damage: older concrete buildings and so-called soft-first-story buildings, which are edifices with garages, large windows, or any other feature that compromises their structural integrity. Thousands of these buildings are scattered around Los Angeles: apartment complexes, schools, hospitals, office buildings, and warehouses, for example. Retrofitting them would require such measures as reinforcing the connections between walls or adding additional first-floor walls to provide more lateral strength.

Not surprisingly, businesses are balking at the costs. Property owners want to pass the retrofitting bills onto tenants. California may have to issue a public bond, which would introduce state politics into the equation. “As with most things,” says Cocke, the structural engineer, “it’s going to come down to money.”

Jones, though, is undaunted. “Don’t let them say this won’t happen,” she says. “It is going to happen.”

With the city report finished, Jones must decide whether to continue to be the Earthquake Lady or to focus full-time on her research. The USGS’s Cox, who has worked with Jones for fifteen years, says she has an introverted side that the public never sees. “She’s overcome it because she is so passionate about protecting California from earthquakes,” he says. But he’s seen her “go fetal after meeting so many people. She needs to be alone and step away from the moment.”

In the meantime, Jones has returned to an old love: writing music. She studied the cello as a child, but switched to the viola da gamba at Brown, where she became part of a Renaissance music group. She put it aside to devote herself to her career and to raising her children. Now she’s playing and composing music again. Her latest composition deals with climate change, correlating a rise in pitch with the increase in the planet’s temperature over the last 130 years. As the piece progresses, it rises three octaves. She plans to perform the piece with fellow musicians this summer. “Making music around the theme is a challenge,” she says, but adds that it’s yet another way to make science resonate with the public. That is, after all, her greatest passion.