"You are teaching murderers and rapists.” My mother repeats it into the phone, louder. “These people have committed heinous crimes. You went to an Ivy League school. You are wasting your talent. These people don’t deserve you.”

My mother has never been inside San Quentin State Prison, just north of San Francisco, where I volunteer teaching college English. Everything she knows she found online, on Wikipedia. She’s read that San Quentin houses California’s male Death Row, seen a photo of the gas chamber-turned-lethal-injection room with a death chair upholstered in sick, menthol green. Thanks to the Wikipedia entry’s “Notable Inmates” section, she knows men incarcerated there: the Dating Game Killer; the Trailside Killer; the Sunset Strip Killer; the Scorecard Killer; the Night Stalker; Richard Allen Davis, killer of Polly Klaas; Scott Peterson, killer of his wife, Laci, and their unborn child; and, until recently, Charles Manson.

My early teaching at San Quentin mimicked the motivational posters splashed on the classroom walls. “Sink or swim!” “Mistakes are proof that you’re trying!” “Enthusiasm ignites greatness!” I was just out of college. My teaching was guesswork. But that was okay. The mutual desire to live up to each other’s expectations as students and teacher carried the class, and I’d walk out of the front gates feeling good. Validated. Purposeful. Behind our well-meaning backs, some officers referred to volunteers as “hug-a-thugs,” shaking their heads at our savior complexes, our ignorance of whom we were dealing with.

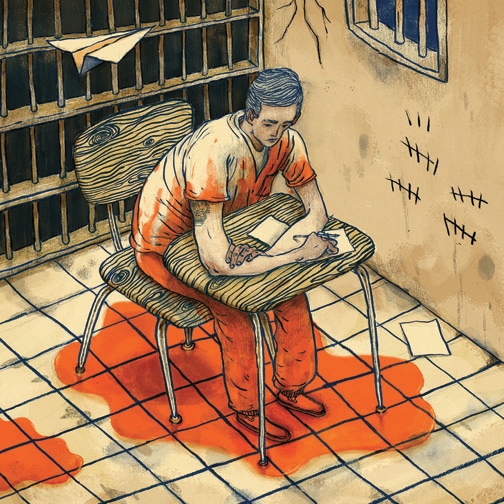

I know that there are volumes I don’t know and other sides of San Quentin and the men incarcerated there that I don’t see. Sometimes I call San Quentin’s education building Candyland. Make Believeopolis. The Bubble of Light. Some men call the classrooms Neutral Territory, Sacred Ground, and San Quentin’s Switzerland. These classrooms are nowhere and anywhere, clean sheets of white paper where we rework old stories.

People ask if I know my students’ crimes. The fact is I know very little. Some men offer their histories, but I don’t ask for them. In a way, not knowing is part of what allows us to laugh together, what allows the work to get done. Maybe I’m delusional. As my mother reminds me, these men are in prison for a reason.

The thing is, the men my mother knows at San Quentin are not the men I know. I know Bruce—his humpback and cane, his endless, slap-happy grin—who tells me about his life in southeast D.C. because I lived in the District once too. (I’ve changed the men’s names here to protect their privacy.) I know Jackson, his BFA from Wesleyan and MFA from Mills, who arrives to class with a rolled-up New Yorker tucked under one arm. I know Ron, his cornrows and huge gold Star of David; we’ll go to De Beer’s where he’ll buy me a rock, he says, once he gets out. I know Javier, whose mother made the best pupusas in all of El Salvador, and Jesse, three-time winner of the San Quentin Marathon. I know Madhu, who wrote Salvation Allah Unity at the top of every assignment.

After five years of teaching at San Quentin, I know now life does not lie in wait outside prison walls. Inside that stripped place, what makes us human—fallible, flawed, redeemable—comes into focus. In San Quentin’s classrooms, we are not sinners or saviors. Not voyeurs or young people adrift. We are not women enjoying the rapt attention of men or lonely men longing for freedom. We are just students and teachers, trading lessons. At least that’s what I choose to see.

Alessandra Wollner ’10, an MFA candidate at Ohio State, continues to teach creative writing at San Quentin.

Illustration by Tony Huynh.