Scientists have long focused on Myc genes for their link to such cancers as leukemia and a type of lymphoma. But a new study concludes they may also help certain animals live longer.

A team of Brown scientists knocked out one of the two Myc genes in mice, causing them to live an average of 15 percent longer. The genes are found in all animals, from ancestral single-celled organisms to humans.

“The animals are definitely aging slower,” says John Sedivy, the Hermon C. Bumpus Professor of Biology. “They are maintaining the function of their organs and tissues for longer periods of time.”

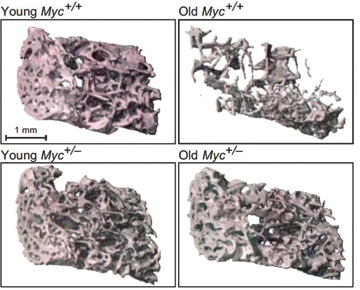

The results varied slightly by gender. Females lived 20 percent longer and males 10 percent longer. The animals were also less likely to develop osteoporosis. They maintained a stronger immune system, produced less cholesterol, and exhibited better coordination.

Sedivy says it might one day be possible to target the Myc genes in humans to slow the process of aging or, more likely, enable humans to have healthier lives.

The findings were published in the journal Cell in January.

NO BONES ABOUT IT

Young mice have good bone density whether they have two copies (top row; +/+) or one copy (bottom row; +/-) of the Myc gene. As they age, researchers found, mice with just one copy maintain better bone density and stay healthy longer.