When physician Armand Sprecher ’89 arrived in Liberia this summer, he

went straight to the country’s capital, Monrovia, and a hospital where

about 120 beds had been set up for people with Ebola. Sprecher, who is

coordinating the Doctors Without Borders (DWB) response to the Ebola

outbreak, ordered a new count of patients. He realized the hospital

would need more than three times as many beds.

The Ebola outbreak in western Africa has continued to worsen ever since it erupted in Guinea in late 2013, proving to be far worse than anyone expected. Sprecher, a specialist in filoviruses, the family that includes Ebola, coordinates the efforts of 200 DWB staffers in Liberia, Guinea, and Sierra Leone, plus an additional 1,200 local medical personnel. By September, the World Health Organization (WHO) was reporting 4,366 cases and 2,218 deaths in five West African countries. In October, the WHO predicted 21,000 cases by November.

“It’s bad,” Sprecher says. “It’s really very, very bad. And we don’t have a handle on it.”

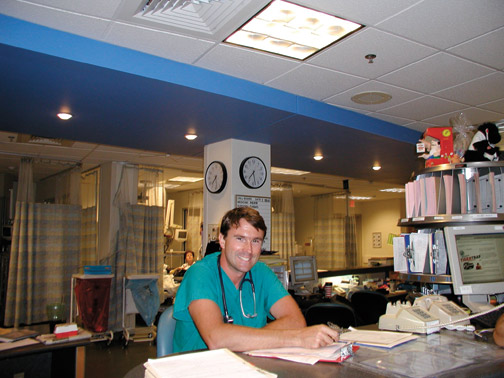

Sprecher concentrated in cognitive science at Brown and went to medical school at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia. He completed his residency in 1997 and bounced around as an emergency room doctor in Nebraska, Wyoming, and New Jersey. Before joining DWB full-time in 2003, he occasionally joined overseas missions to health crises, working, for example, in Angola in 2000. With DWB he also helped treat viral outbreaks in the Democratic Republic of Congo in 2007, and his passport is stamped with the locations of previous outbreaks of Ebola and the related Marburg virus. He met his wife, a Belgian epidemiologist also with DWB, during the 2000 Ebola outbreak in Uganda.

The WHO does not expect the spread of the virus to be under control for many more months. Even the quarantine in Liberia has hampered treatment efforts. In October Sprecher told the Financial Times that when he tried to transport tents from Kenya into Liberia for a clinic, Kenyan authorities blocked the flights. He also points out that relief efforts are complicated because Ebola has hit big cities, where people are concentrated, and because Western Africans travel frequently across borders.

Sprecher adds that among the obstacles facing health care workers are the cultural beliefs of West Africans. He believes that if locals closely followed health workers' instructions, the outbreak would end quickly. Those instructions include avoiding close contact with sick relatives and touching the bodies of the deceased at funerals. “That’s not a trivial thing.” Sprecher says.

However, Sprecher remains optimistic and has criticized those who believe Ebola will continue for years in the region. In late September, he told the Associated Press that diseases, such as Ebola, that linger in the environment usually undergo changes that make them less deadly and more difficult to transmit.

In July, Sprecher’s colleagues were involved in the decision to withhold the experimental drug ZMapp from an infected doctor in Sierra Leone who later died. ZMapp is the same medicine that was later provided to two U.S. doctors who survived the disease.

“We are routinely accused of conducting nefarious experiments on the population there,” Sprecher says. “There were considerations of ‘What if we give him this medicine and he dies?’”

Before the Ebola outbreak, Sprecher was working at DWB on developing disease-tracking software. That will just have to wait.