Once, while researching a magazine article about medical hypnosis, Lois Lowry allowed a hypnotist to “regress her age.” Soon she was six years old, standing barefoot under a pine tree in her grandmother’s yard in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. She felt the pine needles under her feet. She smelled her grandmother’s roses. She heard a mourning dove cry in a nearby tree. Lowry was unimpressed by the hypnotist’s success. “I can do that any time I want,” she shrugs. “If I were home alone and writing about a six-year-old, I could become a six-year-old and be inside that six-year-old.”

But Lowry’s best and most influential novel may be The Giver, which won the 1994 Newbery. Set in a nameless community that prizes “Sameness” and predictability, The Giver is the story of twelve-year-old Jonas and his growing realization of the enormous price his community pays for its seemingly perfect life, a life without prejudice, violence, inequality, or even rudeness. In this community, love is a word too broad to have meaning, and citizens who have reached puberty must take a pill each day for the rest of their lives to prevent “Stirrings.” When a hungry four-year-old Jonas says he is starving, he is taken aside and corrected. He is hungry. No one in the community, he is told, “was starving, had ever been starving, would ever be starving.”

The Giver, the first in a quartet of novels, has sold more than five million copies and taken its place alongside The Catcher in the Rye and To Kill a Mockingbird in the middle school canon. (All three are regulars on the American Library Association’s Top 100 Banned or Challenged Books.) “It’s difficult to imagine, in our post-Hunger Games world,” novelist Robin Wasserman wrote two years ago in a New York Times Book Review appraisal of The Son, the fourth book in the quartet, “how unusual and unsettling it was [in the early 1990s] for a children’s book to touch on euthanasia, suicide, and murder, to couch it all in a bleak vision of political and emotional oppression, and to leave its protagonist’s ultimate fate undecided. In many ways, Lowry invented the contemporary young adult dystopian novel.”

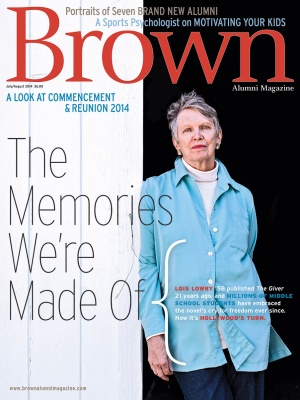

At the heart of The Giver is the subject of memory. Lowry

describes her own memory as “eidetic”—so visually vivid that her

recollections are almost cinematographic. She has striking blue eyes,

short silver hair, and the friendly, slightly reserved manner of a shy

person accustomed to making conversation with strangers. Her

memories from the childhood years when she lived in her grandparents’

stately house are still palpable. She remembers the African American

cook, a nurturing figure in contrast to Lowry’s cold and distant

grandmother. Lowry remembers the rage she felt as a child at the

injustice that the cook had never been to school, had never learned to

read or write. She remembers all the adult talk of the Pacific, a

distant place where her father, a career army officer whose face she

struggled to remember, was fighting a “war,” a word she had sometimes

heard but didn’t understand. And she remembers her mother reading to

her the first book that revealed what strange and powerful things books

could be.

Lowry’s bedroom was across the hall from her sister’s, and before bed

each night their mother would sit in the hallway between the two

darkened rooms and read aloud. One night she began reading The Yearling.

It was, Lowry says, “the first time I had ever become so one with a

book character.” In Lowry’s nine-year-old mind, she and Jody Baxter had

much in common, because he looked like her—she could tell from the

illustrations in the 1946 edition—and loved animals as she did.

But unlike Lowry’s pleasant childhood, in which her grandfather was

president of the local bank and the family played Chinese checkers in

front of the fireplace each night, the Baxters “lived this life of

terrible hardship and deprivation,” Lowry recalls, as they struggled to

survive in the swamps of central Florida. In one illustration that

Lowry vividly remembers, Jody is keeping vigil over his Pa, who has

just been bitten by a rattlesnake. The Yearling was nothing like The Bobbsey Twins or Mary Poppins,

examples of the books Lowry usually read, books in which “nobody really

suffered,” she says. “These people really suffered. And that was

overwhelming to me.”

As Jody’s snakebitten father teeters on the edge of death, the boy

buries his face in the bed, praying. He was torn with hate for all

death, Lowry’s mother read aloud, and pity for all aloneness. It was

the first time Lowry had seen her mother cry, and though Lowry sobbed

along with her, she didn’t realize why until much later. As an adult,

Lowry understood that The Yearling had done for her mother the best of what books can do. She wasn’t crying for the boy in the story; she was crying for herself.

“She’s a woman alone with three young children,” Lowry recalls. “Her husband is on an island in the Pacific where this war is raging.”

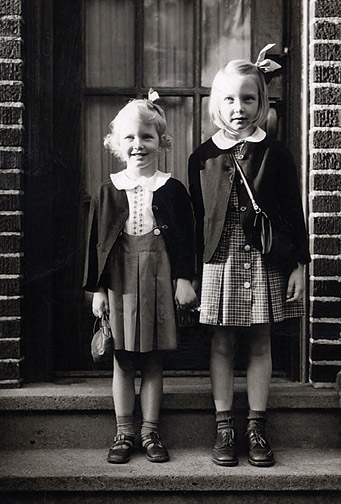

Lowry’s older sister, Helen, thought The Yearling

was boring. Lowry often reflects on her relationship to her sister, and

many of her stories about Helen capture how different they were. Helen

was the glamorous sister, the one who always kept her clothes clean and

her nose wiped. The one who knew the right thing to say. After only a

few chapters of The Yearling, Lowry recalls, Helen shut her door and went back to reading Cherry Ames, Student Nurse.

When Helen started first grade, she would come home and play school

with Lois, who was then only three. She taught Lois everything she’d

learned about how letters made sounds and sounds made words and words

made sentences. As a result, when Lois entered first grade, “I became a

problem for my teacher,” she jokes. Lowry was given permission to read Anne of Green Gables while her classmates struggled over Dick and Jane.

She eventually skipped second grade, which meant missing the

second-grade class trip to the teacher’s farm, where the kids got to

ride ponies. She still remembers the lonely feeling of walking past the

open doorway of her school’s second-grade classroom, hearing her

first-grade friends having fun without her. That feeling of being

singled out, separate and alone, would play an important role in her

fiction.

Helen went on to attend Penn State, where she became a home economics

major nominated for homecoming queen. When the time came for Lowry to

pick a college, she applied to Pembroke to pursue her dream of becoming

a writer. Her father, whom she describes as “a military man, accustomed

to underlings (which included his wife and children) obeying his

orders,” told her: “Over my dead body.” He wanted Lois to follow her

sister to Penn State. But, as Lowry recalls in “Train Rides,” her essay

in The Brown Reader: 50 Writers Remember College Hill, “I had visited her there, had glimpsed her sorority-centered life, and wanted no part of it.”

She overcame her father’s resistance by winning a scholarship. Once she

arrived on campus, she enrolled in a sophomore-year writing workshop

with Professor Charles Philbrick. It made her feel that being a writer

was really possible. “Each time I left his office and walked back to my

dorm,” she writes in “Train Rides,” “it was in a state of exhilaration,

of a yearning for experience, almost giddy with a love of language and

its possibilities.”

Still, this was in 1956, when women, as the saying goes, attended

college to get their “MRS degree.” The teenaged Lois Lowry considered

herself “deeply literary—I didn’t think of myself as somebody who was

there to get a husband. And yet that’s the form our social life took.”

She met a Brown man in the NROTC program who soon gave her his

fraternity pin and then an engagement ring. After he graduated, he was

posted to a naval base in San Diego. At the end of Lowry’s sophomore

year, she dropped out of Pembroke to marry and be with him. She was

given the book The Navy Wife

as a wedding gift, and, just as her father’s peripatetic army career

had taken her childhood family to Hawaii, New York, and Tokyo, so her

marriage to Donald Lowry took the young couple from San Diego to New

London, Key West, and Charleston, and then, after his naval obligations

were over, to Cambridge so he could attend Harvard Law School.

Finally settling in Portland, Maine, they raised their four kids in an

old farmhouse full of books, where, Lowry writes in her memoir Looking Back: A Book of Memories,

“there was always a dog asleep on the kitchen floor, a cat curled on a

windowsill, a guinea pig in some child’s bedroom, and a horse in the

barn.” Even amid the busy chaos of her life as a mother, Lowry

continued to write and send her stories to magazines. Her rejection

letters, she recalls, “were nice rejection letters,” and they

encouraged her to keep writing.

Her luck changed in 1975, when Redbook published her story

“Crow Call.” Intended for adults, it was an autobiographical story told

from the point of view of her nine-year-old self. It centered on a

brightly colored men’s wool hunting shirt she had longingly admired in

a shop window. Her father had bought it for her when he was home on

leave, even though it was so large it hung below her knees. He

“probably saw the purchase as a way of endearing himself to a daughter

who was a virtual stranger to him,” Lowry writes in Looking Back.

“If so, it worked.… I loved that shirt. I loved my father for buying it

for me. I loved the entire world for being the kind of world where such

a shirt, and such a father, existed.”

When her own children were teenagers and needed less of Lowry’s time

and attention, she finally finished college, earning a bachelor’s

degree at the University of Southern Maine in 1973. She began work on

her first book after an editor of young adult books who’d been

impressed by “Crow Call” asked if she wanted to write a novel. All the

giddiness of libraries and words came back to her, and suddenly “I

wasn’t a very good housewife anymore,” Lowry says. On her website she

writes, simply: “My children grew up in Maine. So did I.”

Lowry and her husband divorced in 1977. Faced for the first time with

having to make a living, she took on freelance magazine assignments.

She didn’t need to do that for long. That year her first novel, A Summer to Die,

was published to critical acclaim and commercial success. In it, she

returned to a story she had been telling herself about her sister,

Helen, for many years. When Lowry’s husband was in law school, Helen

had died of cancer at the age of twenty-eight. At the time, Lowry had

been broke and exhausted. The couple had just had their fourth child

and lived in what she calls a “crummy Cambridge apartment” where they

could barely scrape together the $90 rent.

Lowry remembers her desperate need to tell someone—anyone—about her

sister’s life. Lowry’s husband had been too preoccupied with school to

sit and listen for very long, so Lowry had turned to her oldest

daughter, who was four. “Even my child, after a while, was bored with

that,” she says. “So I think it’s a story I began to tell to myself.”

In books, Lowry writes in Looking Back, “I would re-create

these sisters fictionally again and again: the older, poised and

competent; the younger, eager and impetuous. I named them Molly and

Meg; Natalie and Nancy; Jessica and Elizabeth.

“They are always Helen and me.”

Years later, photographs of Helen hung on the walls of the nursing home

where Lowry’s father, then ninety, lived. His memory was failing.

“That’s your sister,” he said happily. Then, puzzled: “I can’t remember

exactly what happened to her.”

Lowry hated to break his heart, but she felt she had to be honest. “She

died, Dad,” she told her father, and watched his face fall. This

happened again and again. And she began to wonder whether it might be

easier—safer, more comfortable—to forget.

And so Lowry began writing The Giver. She asked herself a

question: What if you could manipulate human memory? What if no one had

to remember things that had once made them sad, or scared, or

embarrassed? Lowry had never been a fan of science fiction or fantasy,

but she knew that this book would have to be set in the future.

In The Giver, Jonas is selected to train for the most

honored role in the community: the Receiver of Memory. The current

Receiver of Memory, a man prematurely aged by the burden of all the

memories he must keep, becomes the Giver, who will forget every memory

once he has passed it on to Jonas. “The time of the memories,” as the

Giver describes it, was messy and painful. Jonas will feel things no

one in his community has ever felt: the pain of war and death, the joy

of experiencing snow and festive holidays for the first time. Long ago,

“back and back and back,” as the Giver puts it, the community gave up

its communal memories so that it could remain untroubled and could

avoid making “wrong” decisions.

The memories the Giver passes on to Jonas are vivid: a soldier dying,

thirsty, on a battlefield while around him dying horses kick their

hooves toward the sky; a family celebrating Christmas; poachers hacking

ivory from an elephant; another elephant coming forward to touch its

maimed companion and wail over its loss. No one person experienced all

these events. They are the collective remembrances of human history.

Only the Receiver is burdened with these memories; only the Receiver

has access to the treasury of books from the past. His role is to

remember the world before “Sameness.” He bears the burden of history

alone, so that when the community is faced with an unfamiliar problem,

the elders may turn to him for wisdom.

Thus Lowry reimagines the aspect of memories that intrigues her the

most: their individuality. Nobody in the world has exactly your

memories. “Even if you and your twin brother went to the same birthday

party,” Lowry is fond of saying, “you’ll both remember it differently.”

Even her memories of her sister, crucial as they are to Lowry’s sense

of self, are her memories, experienced through the prism of her own

personality. Lowry was surprised, for example, when Helen’s widower

told Lois that he’d always thought of her as the outgoing sister.

And so, while receiving these memories, Jonas discovers that what he

thought was happiness is in fact a bland contentment that obscures

subtle lies and hidden horrors. By giving up pain and spontaneity and

individuality, the community also gives up true joy—and love. No

experience from Lowry’s life exemplifies this tension better than the

story of her son Grey, an Air Force flight instructor stationed in

Germany, where he had married a German woman in a beautiful ceremony

“conducted,” Lowry says, “in a language I do not speak and cannot

understand.” One passage was in English, however; it was from the Book

of Ruth: Where you go, I will go. Your people will be my people. “How

small the world has become,” Lowry thought happily to herself. “We are

all each other’s people now.”

In 1995, two years after The Giver appeared and when Grey’s

daughter Nadine was nineteen months old, Grey called Lowry on Mother’s

Day to tell her that Nadine had sung him the dopey theme song from Barney

in her crib that morning—I love you, you love me…—and Grey had almost

started to cry. “I never really got it—the parent thing,” he told his

mother. “And now I do.”

A month later, Lowry’s daughter-in-law Margret called from Germany with the news that Grey’s plane had crashed and he had been killed.

As time passed, Lowry thought again about what she’d wondered years

before: might it be easier—safer, more comfortable—to forget the

suffering in our lives? Lowry says that in the case of her son she

wouldn’t give up the memory of that day, entwined as it is with

memories of Grey’s life: when he was born, when he walked for the first

time, when he became an Eagle Scout, when he graduated from school.

“It’s who we are, it’s what we’re made of—the combination of good and

bad memories,” she says. “The memory of him includes the memory of his

death. I can’t conceive of obliterating that, because to me that’s an

obliteration of my son.”

One of the most mysterious concepts in The Giver is

“Elsewhere.” It is where unwanted members of the community go and is

the mysterious place to which the old are “released” after a

celebration of their lives. No one other than the Giver knows where

Elsewhere is; no one else seems the least bit curious about it, even

though the entire world beyond the community is unknown. “I thought

there was only us,” Jonas says early in his training. “I thought there

was only now.”

Lowry remembers an “elsewhere” in her own childhood that influenced The Giver.

When she was eleven years old, she and her mother, sister, and brother

moved to Tokyo to join their father, who was stationed there. The

family settled into an American-style house with American neighbors in

a gated American enclave. The movie theater showed American movies, and

its tiny elementary school taught an American curriculum.

“I am not a particularly adventurous child, nor am I a rebellious one,”

Lowry explained in her 1994 Newbery Award speech. “But I have always

been curious. I have a bicycle. Again and again—countless times without

my parents’ knowledge—I ride my bicycle out the back gate of the fence

that surrounds our comfortable, familiar, safe American community.” She

rode down a hill into a district called Shibuya, “crowded with shops

and people and theaters and street vendors.” She remembers the smell of

fish and fertilizer, “music and shouting and the clatter of wooden

shoes and wooden sticks and wooden wheels.”

Lowry remembers shyly watching the schoolchildren her own age shouting

and playing in their dark blue uniforms, “and they watch me in return;

but we never speak to one another.” She remembers a woman reaching out

to touch her blond hair. The woman said kirei-des—you’re pretty—but

Lowry misunderstood. She thought at first the woman had said kirai

des—I dislike you—and felt ashamed and embarrassed.

To cross elsewhere we must connect with other people, and through them

experience empathy, bravery, and doubt. One of the reasons The Giver

resonates with young people is that in Jonas they see themselves:

someone who at twelve longs to break out of the adult prescriptions

about what to do and what to think. Brought to life by the memories he

has received, Jonas follows his heart, bravely risking his life to save

Gabe, a baby he has come to love. But Lowry insists that all her

characters are heroes in their own way. They all struggle with the

dangers and pitfalls of reaching across a divide to make a human

connection.

“I remember once again how comfortable, familiar, and safe my parents had sought to make my childhood by shielding me from Elsewhere,” Lowry said in her Newbery speech. “But I remember, too, that my response had been to open the gate again and again.”

Breaking down the walls between here and Elsewhere—the things that

separate us from others—is, at the end of the day, the work of books.

It’s what motivates us to read, and what inspires Lowry to write.

“Each time a child opens a book, he pushes open the gate that separates

him from Elsewhere,” Lowry said in her Newbery speech. “The man that I

named The Giver

passed along to the boy knowledge, history, memories, color, pain,

laughter, love, and truth. Every time you place a book in the hands of

a child, you do the same thing.”

Beth Schwartzapfel is a BAM contributing editor.