On a recent Tuesday, I woke up in my apartment in St. Petersburg, Florida, a little groggy from the night before. “How many drinks did I have last night?” I wondered. Who knows? Just add it to the $100,000 bill: the approximate sum of my alcohol expenses since graduating from Brown.

I started drinking when I was nineteen. The habit slowly accelerated from a release to a fixation. Alcohol made me feel invincible and uninhibited, free of any need to question my actions. I have gone in and out of AA and other support groups over the years. But, as anyone who has experienced addiction knows, part of the challenge is that your impulses are divided. You know objectively that having a drink will be bad for you. However, the mind caves in on itself in the absence of alcohol. Sobriety becomes its own form of madness—a halting, dissociative whirlwind manipulating the brain into making booze the number-one priority.

My time at Brown was misspent in many ways. I was drinking too much beer, but I had a larger problem: not connecting with those around me. I interacted with people through my contributions to the humor magazine, through comedy shows, and in my satire publication, Kent. In the end, though, I wasn’t able to break from my consistently silly persona to bond with my classmates.

That kind of big picture wasn’t on my mind on that Tuesday in St. Petersburg, though. I just wanted to find my wallet. At the bar where I had been drinking the previous night, the owner said he didn’t know where my belongings were, but fifteen years of these kinds of searches told me I shouldn’t quite trust him. After all, I had been flirting with his wife the night before. I spotted my cell phone behind the counter. I grabbed it and left.

I found my car the next day near a favorite coffee shop. Several days later, I received a text message from a friend: my wallet was at yet another bar. I didn’t even remember going to that one, a common experience for me. Nonetheless, it felt like fate was on my side again, that the universe was pushing me toward a full recovery.

The universe, however, wasn’t in a hurry. A few months later, I started attending Narcotics Anonymous meetings. I don’t have a drug problem, but I wanted to avoid hearing the Lord’s Prayer recited at AA. I felt vulnerable, and my vulnerability felt raw in a religious setting. Ninety days after I’d begun with NA, I caved. I knew myself only as someone bent on his own annihilation. Good health and safety were attainable, but they were also out of reach.

In July I moved to Austin, Texas. I am now a three-hour drive, rather than a three-hour flight, from my son, who is seven. I’ve repeatedly made excuses in my relationship with him, part of a pattern of misleading those I love to protect my damaging addiction.

At the time of this writing, my struggle with this disease continues. I confess that I drunkenly misplaced my car again while I was writing this piece. I provide my story here to explore my humanity more fully and to try to exhibit the unvarnished truth for others suffering from the disease. I am eternally hopeful that knowing that it’s five o’clock somewhere won’t always feel like an invitation to open a bottle.

Kent Roberts, a comedian and author, is online at TGIKent.com and can be reached at [email protected].

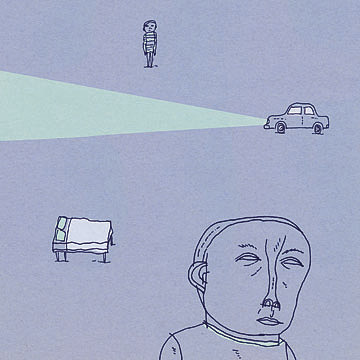

Illustration by Jordin Isip