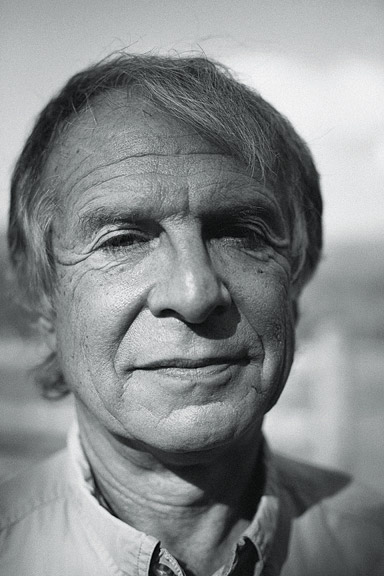

For many people, a terminal illness is, at best, an opportunity to get one’s affairs in order. But for Ed Pincus ’60, who was diagnosed two years ago with the blood disease myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), it was an opportunity to live life more deeply. As his MDS progressed to leukemia, he spent his last years making his final film, One Cut, One Life, a sequel of sorts to his deeply personal and influential 1982 documentary, Diaries (1971-1976). He died on November 5, 2013.

The film was initially inspired by the sudden deaths of two people close to Small. In 2009 her friend, the sculptural artist Susan Woolf, was murdered. Six weeks later, a driver fleeing police after a robbery in New York City hit and killed film editor Karen Schmeer, a frequent collaborator with the documentarian Errol Morris. Schmeer was living with Small at the time. In 2010 Pincus encouraged Small to pick up a camera to help her cope with the trauma. She was reluctant. But a year later, after Pincus was diagnosed, the two friends realized they could make a film about how they were both experiencing death. The film became a way for both of them to frame their ordeals, and to create a document that would explore their collaboration.

One Cut, One Life has painful sequences—hospital visits and Small’s memorials to her friends—but the film primarily focuses on the unique camaraderie between the two filmmakers, as well as on their life passions. Its uncompromising self-exploration is reminiscent of Diaries, which was shot between 1971 and 1976 and is considered a seminal achievement in self-revelation. In Diaries, Pincus turned the camera on himself, and explored his life in raw detail, including the difficult phase in his marriage when he and his wife, Jane Pincus ’59, had an open relationship.

“Ed took it further than anyone else had done at that point,” says his former student Ross McElwee ’70, who followed Pincus into first-person filmmaking with such documentaries as Sherman’s March and Time Indefinite. “He opened up my, and others’, thinking about what a documentary could do.”

Pincus didn’t discover the medium until he was a graduate student at Harvard. While at Brown—which the Brooklyn-born Pincus said he attended because the College Green reminded him of Ebbets Field at night—he studied philosophy. In the Blue Room he met Jane Kates, an artist and the eventual coauthor of the classic women’s health book, Our Bodies, Ourselves. She was reading André Malraux’s La Condition Humaine. “I said, ‘Oh, I read that little book,’” he recalled. “And eventually we were an item.”

Pincus was passionate about photography, particularly about framing light with his camera. But at Harvard he saw Showman, a 1963 documentary by Albert and David Maysles, and was hooked by the form. “It was an imprinting phenomenon,” Pincus said. “All I had to do was see the camera and I knew what it meant and what it had to do.”

He became one of the first filmmakers to use the new “sync-sound” technology, which made the process of filmmaking more intimate by allowing a single person to capture image and sound with mobile equipment. He went south to document the civil rights movement in Black Natchez, then traveled to San Francisco to depict a hippie commune in One Step Away. In 1971—the year the Loud family invited a camera crew into their California home to shoot An American Family, the PBS series that inaugurated reality television—Pincus began shooting Diaries.

Unlike An American Family, Diaries never connected with mainstream audiences. New York Times critic Vincent Canby wrote, “It’s difficult to understand why anyone would want to make a movie of his own life, unless one were a filmmaker in search of a subject.” Although Canby called Diaries “painfully authentic,” he concluded, “It’s not only about the generation once labeled ‘me’; it’s a demonstration of it. Me, Me, Me!”

In an essay he wrote for Documentary, an International

Documentary Association publication, McElwee articulated a different

view. “One of the most remarkable nonfiction films ever made,” he

wrote. “It’s luminous in its depiction of the beautiful and profound

weave of everyday life … the film was a daring attempt to fuse art with

real life.”

The Film Society at Lincoln Center hosted a retrospective of Pincus’s work in 2012, in which it described Diaries as “the logical conclusion to a tendency in cinéma vérité documentary towards more personal, less ‘newsworthy’ subjects. With Diaries, Pincus brought the very idea of a diary film to a whole other level.”

Pincus never achieved the fame of the 1960s filmmakers who preceded

him—Frederick Wiseman, the Maysles brothers, and D.A. Pennebaker—but he

was well known among his peers for breaking new ground. He founded

MIT’s film program, where he and cinéma vérité legend Richard Leacock

were guiding lights. At MIT and Harvard, Pincus taught such budding

filmmakers as McElwee and Terrence Malick. Pincus also wrote the widely

used textbook Guide to Filmmaking and coauthored its successor, The Filmmaker’s Handbook, with Steven Ascher.

But Pincus fled Boston as a result of an event he referenced in Diaries.

One of his film contacts, a mentally unstable political activist named

Dennis Sweeney, came to believe that Pincus was part of a grand Jewish

conspiracy. Claiming he was receiving messages in his teeth, Sweeney

traveled to Boston to threaten Ed and Jane Pincus and their children.

Frightened, the Pincuses packed up in the early 1980s and moved to a

farm they owned in Roxbury, Vermont. Sweeney eventually murdered

political activist and lawyer Allard Lowenstein and was declared

criminally insane. He was released from prison in 2000.

In Vermont, Pincus continued to pursue his passion for photography. He

worked for years on a book of portraits of Roxbury locals, creating

what’s still a work-in-progress document that is both vivid and

disturbing. He gave up filmmaking and took up farming, with Jane

working at his side, as well as painting. The couple worked on new

editions of Our Bodies, Ourselves

and raised their two children. Ed tried growing garlic and other crops

but settled on flowers and ran the successful Third Branch Flower farm.

Although for the first few years Pincus would travel to Boston to teach

at MIT, he didn’t make a film for more than twenty years. But when the

New England Film and Video Festival invited him to be a member of its

jury in 2002, he met Small, who joined with him to make 2007’s Axe in the Attic,

about the impact of Hurricane Katrina on those forced to flee their

homes. The film shows Pincus and Small, in front of and behind the

camera, as they wrestle with their own emotions in response to the pain

caused by the disaster.

This fall, in a converted shed on his farm in Vermont, Small and Pincus were doing the final edits on One Cut, One Life

as they prepared to submit it to film festivals. Jane, who appears in

the new film, continued to serve as her husband’s muse and primary

support. Pincus said he hoped that the documentary would show how, “in

everyone’s life, there is a novel like Tolstoy, not literally, but with

the complexity of narrative.”

Doctors had predicted he wouldn’t live beyond March 2013. So, as the

months passed that date, he sometimes defaulted to life as normal. Yes,

he was limited in his functions, but “as long as my mind is sharp,” he

said. “I’m happy.” He was sanguine enough to say that One Cut might “not necessarily be my last film,” although plans were in place to hand the running of the farm to his son, Ben.

Pincus passed away quietly in his home, high up on a hill in Vermont, surrounded by his family. One Cut, One Life is due to be released this year.

Tom Roston writes the column Doc Soup on PBS’s POV documentary website. Follow him on Twitter at DocSoupMan.