It was one of those sunny autumn afternoons that smell of apples and falling leaves. Thanksgiving break was just a few days away. I checked the date as I walked out of Miller Hall and headed for the Thayer Street market. November 22, 1963.

I was happy at college, but I didn’t know that then. Fear of what

seemed like a hellish future eclipsed my good feelings. I knew I had to

get married, but my attempts at dating were spectacularly unsuccessful.

I was hoping to find a career, but the only things I liked doing were

sleeping and reading. How would I manage? My delight in the campus—my

friends, the solace of books, skating at Aldrich Dexter, and exploring

Fox Point—was dulled by anxiety.

We stayed up late debating whether it was better to die in a fiery

flash, be captured by the Russian soldiers who were waiting off the

coast, or slowly starve the way characters did in On the Beach by Nevil Shute, set portentously in 1963. In late-night conversations we quoted the elegant despair of Edna St. Vincent Millay—my candle burns at both ends/ it will not last the night. In class we studied the elegant despair of T. S. Eliot—I had not thought death had undone so many.

The question was how we would survive. The answer, my friend, was

blowin’ in the wind. Would it all end with a bang, or with a whimper,

as Eliot wrote? Fire or ice, as Robert Frost wrote? One thing we knew:

it was going to end, and end soon.

So that sunny November afternoon when I saw a girl from my class

sobbing as she stumbled down Thayer Street, I wasn’t surprised to find

the world indeed coming to an end. The president had been shot. The

president had been shot in Dallas in a motorcade with the governor of

Texas. The president was at Parkland Memorial Hospital in Dallas.

Jackie’s chic clothes—her pink suit and pillbox hat—were covered with

blood. The doctors were giving the president transfusions. By the time

the afternoon sun sent its long shadows across the lawns in front of

Sayles Hall, the president was dead.

In those days the only publicly available television on campus was a

small black-and-white set in the Blue Room, where on that day it seemed

the whole student body had crowded in, all of them standing or sitting

on the floor and draping themselves over the few chairs to watch the

long, sad four-day weekend of national mourning. The picture was

grainy, the images tiny, but the little box seemed to hold the whole

world. There was the young Walter Cronkite with his heavy black glasses

and moustache, choking up as he announced that the president had been

pronounced dead. There was CBS reporter Tom Pettit in the chaotic

basement of the Dallas Police Station trying to keep up with the jumble

of events. A pale Lee Harvey Oswald was saying he hadn’t done anything

as he was pushed toward a man named Jack R:uby. Then there was a

popping sound, and the next minute Oswald was dead and the screen was

filled with a shoving crowd of men.

Before that weekend, television was where we watched the Mouseketeers and I Love Lucy.

Now our history was unfolding in miniature before us, in black and

white, with the tinny sound turned up as high as it would go. There on

screen was little John-John saluting his father’s coffin, and there was

the weeping widow, with her sad face and lovely clothes, standing

entirely alone with her two children. There was the riderless horse,

bucking in the autumn sun. I watched. I went for walks. I came back to

listen. The clatter of hoofs drowned out the guns of the funeral

salute.

As terrible as that November day fifty years ago may have been, its

memories have not entirely overwhelmed those of my days and nights at

Brown. My first days as a college freshman were passed in a haze of

anxiety. My roommate was a beautiful blue-eyed princess from the

Midwest who had special study clothes, date clothes, and classroom

clothes—all pink or baby-blue—and who read sitting up straight at the

desk on her side of the room. The desk on my side was piled with

papers, books, coffee cups. I read in bed, often under the covers, and

I tried never to change my clothes. Trapped together on an upper hall

of Andrews facing the back, we seemed helpless in our opposite ways.

Soon we had gathered a few more helpless freshmen who huddled with us

under the high ceilings of the cafeteria and made tea on hot plates

brought from home. To get to class I would wander down the steps of

Andrews and out past the Pembroke Library and down Brown Street.

In the fall of 2012 I returned as a visiting lecturer. I hadn’t been

back for more than an evening or an afternoon since graduation. As a

teacher walking that same sidewalk down Brown Street last fall, I had

vivid, nostalgic flashbacks: of sitting on the grass with friends; of

watching from the high windows of the Pembroke Library as a boy I had a

crush on walked up Meeting Street (did he know he carried my heart in

his pocket?); of buying my first yogurt (then a new, strange thing) at

the Thayer market; of splitting a piece of cherry cheesecake at Gregg’s

(now Au Bon Pain); of spending that weekend in the Blue Room watching

television. Nostalgia! Gone is the anxiety that killed my ability to

appreciate the beauty of the place and the luxury of having nothing to

do except learn. These shimmering images of the past seemed more alive

than memories—I was reliving my experience at Brown, only this time I

was reliving it joyfully.

Nostalgia is the bittersweet memory of the past, literally an ache for

homecoming—the bitterness is the passing of time, the sweetness is our

survival. The Brown campus, it turns out, is nostalgia central for me.

Returning to it was like having a romance with an old friend. I reveled

in the past that I can enjoy now. I did get married; I did find a

career. Recently, dozens of academic papers on nostalgia have been

published at universities from the Netherlands to South Africa, and the

United States. Nostalgia is a good thing, the psychologists all agree.

We use our longing for the past to give our lives meaning. Nostalgia

makes us feel more important and more generous: “It serves a crucial

existential function,” says researcher Clay Routledge of Britain’s

University of Southampton. British researchers have developed the

Southampton Nostalgia Scale (How often do you experience nostalgia? How

significant is it for you to feel nostalgic?) I scored a seven out of

seven. We’ll always have Paris!

What do I remember learning at Brown? How to survive a broken heart.

How to cook an elaborate stew on a hot plate. That my worst fears

rarely come true. How to read a book a week. When Professor David

Hirsch talked to me about Henry James and Edgar Allan Poe, the ghosts

in their stories jumped out at me. I read F.O. Matthiessen’s American Renaissance

with Professor Barry Marks, and I have since written my own books about

those Concord writers—Emerson, Thoreau, and their neighbors, the loony,

impoverished Alcotts. I thought personal style was everything in those

days—how could I be friends with a girl who wore pink? I got a little

smarter. My first roommate and I became good friends after all. I loved

her.

Now I’m smart enough to see that I was with my people at college, a

generation of confused and frightened kids looking for and finding our

answers in books. As it turned out, in spite of the death of a

president on an autumn day, we didn’t die at college, and we didn’t die

soon afterwards. World War III was a fearful, exaggerated chimera. We

didn’t die, and instead we did something much more difficult than

dying: we learned how to live.

Susan Cheever is the author of fourteen books. Her biography of the poet E.E. Cummings will be published in February. She is working on a history of drinking in America.

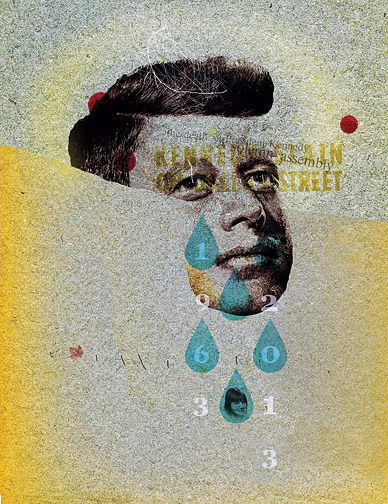

Illustration by Matthew Richardson