After a year of deliveration by two advisory committees, in late October the Brown Corporation announced that the University will not stop investing in companies that produce or burn coal.

“It would be the height of irresponsibility for Brown not to divest,” Parenti, a contributing editor at the The Nation, said. But he added that divestment alone would not bring about substantial change. “It doesn’t hurt the bottom line of the fossil fuel industry,” he acknowledged. “Most firms generate income through bonds or operating profits,” not from the sale or price of stock. He called on student groups to urge the University and local governments to convert to renewable energy sources, which he said would deprive energy companies of revenue.

In January, the Advisory Committee on Corporate Responsibility in Investment Policies, an oversight panel of students, faculty, staff, and alumni, recommended that Brown divest from what environmentalists call the “Filthy 15”: the fifteen largest coal-producing or coal-burning companies in the country.

In April the committee fine-tuned its recommendation and urged the University to divest from “any U.S. generator that produces more than 15,000 [gigawatt hours] of electricity annually from coal” or that buys more than 20 million tons of coal a year. It also recommended divesting from any U.S. mining company producing more than 50 million tons of coal annually.

Among the Filthy 15 is the Charlotte, North Carolina, utility Duke

Energy. Rogers, who is Duke Energy’s chairman of the board, defended

his company’s record at the Janus Forum. He said Duke is shutting down

ninety antiquated coal and oil plants, and he advocates the

“cap-and-trade” system to control CO2 emissions. (Cap-and-trade,

which once had the support of both George H.W. Bush and the

Environmental Defense Fund and which continues to be endorsed by

President Obama and some conservatives, sets a cap on how much air

pollution a company can put out. A company that pollutes less can sell

or trade the remaining pollution capacity to another company.)

Rogers said that technological innovation and marketplace demand for

cleaner energy would move the power industry away from coal, but that

it should happen slowly to minimize economic disruption. Many

developing companies now rely on coal to fuel their economic growth,

Rogers continued, which means any cutback in production might increase

poverty.

“You have to have a nuanced and balanced approach,” he said. “We’re making the transition. You can’t do it overnight.”

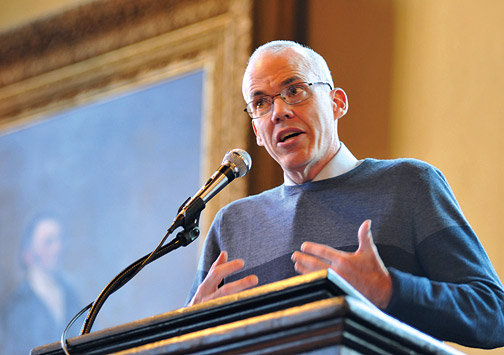

McKibben, who runs 350.org, an environmental group that focuses on

global climate change, was having none of this. Given the rate of

climate change, he argued, there is no time for a gradual approach.

Duke and other power companies, he said, “want the world to hang on [to

coal] longer, far longer than science tells us we can,” he said. “This

is by far the biggest threat to human beings.… The watchword to my

remarks is urgency.”