My father died before we made peace. He and I were never close. I was a provincial transformed by Brown, books, and classier company. My dress and speech and manners and, yes, my thoughts had undergone an upgrade. How could I be his child?

In 1990, a decade after my father died, a community college offered me a job teaching writing in several Connecticut prisons. I hesitated, but ninety days later I found myself in a maximum-security facility. I wondered why I so soon felt comfortable with killers and rapists.

One night, on break, I peered up at a very large black man. Without prelude he told me, “I killed the mutha that messed with my nine-year-old nephews” (“messed with” meant molested). Another man sat through that same class for fifteen weeks, at night, in dark glasses. No one was going to see his eyes.

My father would have understood. He knew firsthand what I was learning, that behind a hard mask sat a hurt boy. His Swedish immigrant father made molds for Gorham Silver. Vain and ambitious, he was cool to a son who limped from childhood polio, one leg smaller than the other. When Dad quit school to do piecework in a factory, his father railed. Dad was proof that Swedes were “dumb.”

Even when my father returned to high school and graduated, hoping to go to college, Grampa did not relent. He had stretched to support his favorite—a daughter—through Pembroke, but now with the Depression there was no money left. Dad had been cast out.

My prison work ended in 2000, and since then I have taught classes for adult women in the foundering city of Holyoke, Massachusetts. The focus is great books—Plato, Shakespeare, Chekhov.

The women’s hands shake when they interview for the class. Their voices crack. Some cry. They ache to crawl out of the hole of poverty.

The mother of the program’s best student this year was angry because her forty-seven-year-old daughter wasn’t coming by as often to clean Mom’s house. “You’re an addict,” Mom told Liz. “Always gonna be an addict. Now you’re addicted to school. You need help.” Liz had been off drugs for a dozen years.

“Who the hell was I kidding that I could do this?” Liz announced to the class.

Others in the room had lived the same pattern—life gets hard, run.

And suddenly I found myself talking to the women about Dad and about my disapproving grandfather refusing funds for college. About how Dad found work and, for ten years through the fury of the Depression, juggled jobs and forestry school to complete a degree. “Finish what you start,” he said. “Do something; do it right.” My father wouldn’t quit.

Only now do I realize that my father has always been standing in my classroom.

Dad, all these years I’ve been teaching, I’ve been trying to make amends—building a road back to you.

Kent Jacobson directs the Bard College Clemente Course in the Humanities at the Care Center in Holyoke, Massachusetts. Reach him at [email protected].

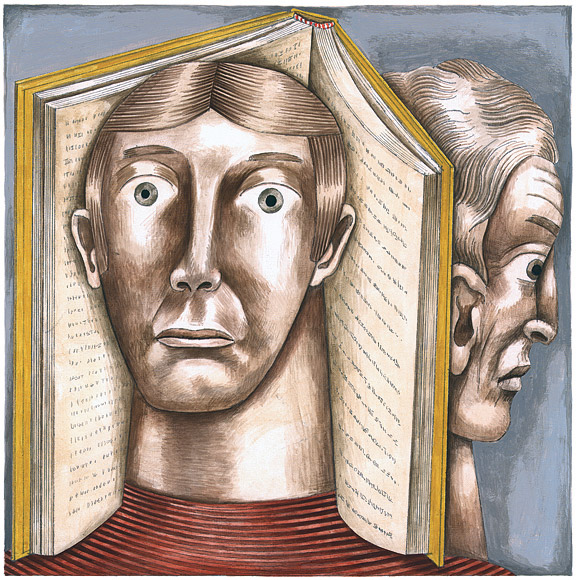

Illustration by Richard Downs