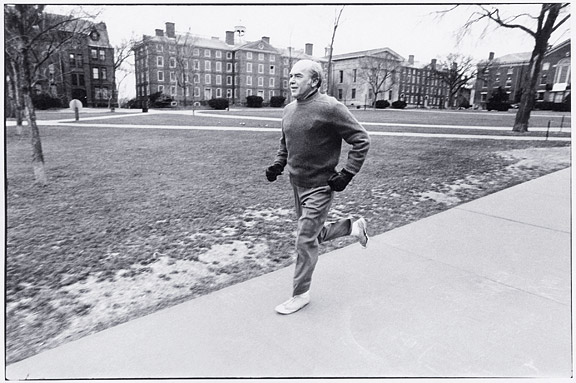

When he was once asked to describe his experience as Brown’s fourteenth president, Donald F. Hornig, who braved the ire of both students and faculty when he guided the University through the fiscal crisis of the 1970s, called it bittersweet. When asked what he would change, he said, simply, “The times.”

Unfortunately, Hornig also inherited a projected $4.1 million budget shortfall that he quickly discovered could drain the endowment in just a few years. Controlling spending came at a steep political and personal price. In order to cut 15 percent from the budget, Hornig slashed student services and even cut faculty.

In the spring of 1975, when his administration threatened to cut financial aid, students protested that this would reduce the already inadequate numbers of minority students and faculty on campus. A group of black students occupied University Hall, and hundreds of other protestors—black and white—circled the building. Hornig conceded to some of their demands but vowed never again to negotiate with students occupying a building. He left the next year to join Harvard’s School of Public Health, where he was founding director of its interdisciplinary programs in health.

When Hornig arrived at Brown, he had already achieved a distinguished academic and governmental career. He also knew the University. An outstanding scientist, he had joined the Brown chemistry department as an assistant professor in 1946 and become a full professor in only five years, at age thirty-one. (He was also one of the youngest scholars elected to the American Academy of Sciences.)

He left Brown for Princeton in 1957, then served as science adviser to presidents Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon. Appointed by Kennedy just fifteen days before his assassination in 1963, Hornig stayed on in the Johnson administration, but suffered from culture shock.

“I was never on easy personal terms [with Johnson],” Hornig told Science magazine in 1969. “He invited me down to the ranch a couple of times, but we were never on a chatty basis. There’s always been a certain gap in attitude between a Texas rancher and an Ivy League professor.”

Hornig worked for the White House for nearly five years, though, and led what is now the Office of Science and Technology Policy, where he was among the early scientists to advocate for the importance of better protecting the environment.

Hornig had already made his most fateful mark as a scientist while working on the Manhattan Project during World War II. A specialist in shock waves, he was working on deep water explosives at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution when a former professor called with a top-secret job offer and a promise that it would include work for his wife Lilli, a fellow chemist he’d met and married in graduate school. Telling no one of their plans, the couple drove to Santa Fe, where they were directed to Los Alamos.

During his seven-year presidency at Brown, Hornig oversaw monumental changes that included the 1972 merger with Pembroke and the creation of the medical school. (He saw Brown’s first class of MDs graduate.) By the time he resigned in 1977, he had put the University back on firm fiscal footing, trimming the shortfall to $636,000.

Accepting Hornig’s resignation in 1976, Chancellor Charles C. Tillinghast ’32 wrote, “I note with satisfaction that the path toward a stable fiscal condition has been laid down.…. Your successor will be grateful that so much of this frequently thankless task has been accomplished.”

In a statement following Hornig’s death, President Christina Paxson observed, “Much of Brown University’s success over the last three decades had its roots in these decisions, for which we remain grateful.”

In 1994, the BAM interviewed Hornig about his career in science, his long-standing commitment to environmentalism, and his fears for the planet—especially global warming.

“We don’t keep our homes clean just so our house guests won’t get sick,” he said. “It goes deeper than that. You want to be a good housekeeper because the house itself has meaning to you. We’ve got to start acting as though this earth has meaning. We’ve got to be good housekeepers.”

In addition to his wife, Lilli, Hornig is survived by two daughters,

a son, a brother and sister, nine grandchildren, and ten

great-grandchildren.