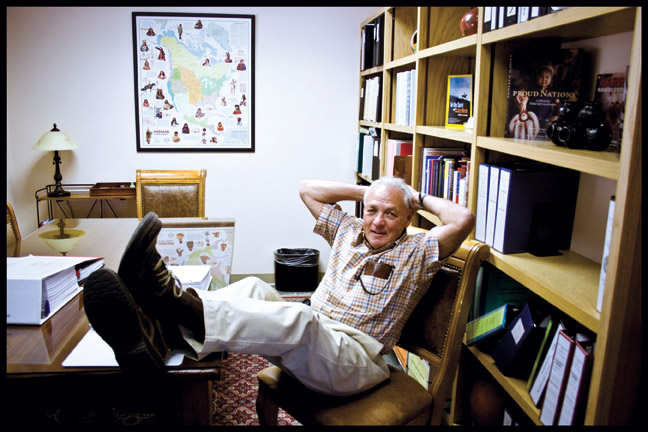

For the last forty years, Michael Gross ’64 has had the same major client at his Santa Fe, New Mexico, law practice: the Ramah Navajos. The tribe lives on a reservation about 100 miles away from the larger Navajo nation. Over the centuries, this has left it more vulnerable to attack. It also hasn't benefited as much from many federal efforts to redress past wrongs done to Native Americans.

“I never decided in a conscious way I would get involved in a civil rights-type of career,” he says. “It never entered my mind, never planned it out. It all happened by chance.”

Gross grew up in New Jersey, the child of Austrian Holocaust survivors. In 1939, they convinced their Nazi captors to release them after promising to leave Austria and join relatives in the United States. They had only two weeks to pack up all their belongings and leave. Family lore has it that Gross’s father and uncle waited anxiously at a train station for his mother. Minutes before the train departed for Vienna, his mother finally appeared. The reason for her tardiness? “I was at the hairdresser,” she said.

But contrary to this story, Gross says his mother was neither vain nor frivolous. He remembers her as a “feisty” woman who instilled in her son a commitment to social justice. Gross’s father worked fourteen-hour days as a tailor at his shop on Manhattan’s Upper East Side.

After graduating from Brown with a degree in international relations, Gross decided to participate in a nascent exchange program between Brown and Tougaloo College, a historically black school north of Jackson, Mississippi. Only two days after his arrival, 10,000 protesters descended on campus as part of what was called the March Against Fear, a 220-mile protest walk from Memphis to Jackson during the sweltering summer of 1966. The protest had a profound influence on Gross.

A year later, while attending Yale Law School, Gross took a clerkship with a private law firm in Phoenix. His first case involved Ramah Navajo, who were coping with limited access to a high school that was so far away the Navajo students had to stay in dormitories.

After joining DNA People’s Legal Services, Gross soon found himself becoming the Ramah Navajos’ chief lawyer. In 1970 he helped organize the first-ever Ramah school board. Within six weeks, the board, with his counsel, had raised $368,000 in federal funds to build a new high school in the heart of the reservation.

Gross argued his first Supreme Court case in 1982, defending the Ramah Navajo School Board’s position that the state of New Mexico couldn’t impose taxes on a construction company building a school on lands owned by Native Americans. He won. This year, a case he began working on nearly twenty-five years ago finally reached the U.S. Supreme Court, where it was argued by a lawyer Gross hired who had more experience before the nine judges.

The case centered on whether the federal government should fully reimburse Native American tribes for certain services the U.S. Secretary of the Interior had contracted out to the tribes between 1994 and 2001, services the department would normally provide. The Supreme Court ruled, 5–4, that the government had paid only part of what it had promised and ordered it to fulfill the terms of the contract.

When Gross now visits Native American communities, he urges them not to

get complacent. “I’m telling them, ‘Look, we won the case, it feels

good, we’re going to get some money. But you haven’t begun to win this

war yet,’” Gross says. “This is a never-ending struggle.”