In the weeks after 9/11, Aisha Bailey worked at the New York City medical examiner’s office. “I would go to autopsies all day,” she says, “and when that got to be too stressful, I needed some sort of artistic channel.” That need for an outlet ultimately led Bailey, now a pediatrician in New Jersey, to a second career as designer and CEO of a line of dolls called Ishababies, which draw their name from her childhood nickname, Isha.

Since college, Bailey had been drawing cartoons for friends’ birthday

cards, and while in New York she created a line of baby-announcement

and gift cards. Her mother, Bernicestine Bailey ’68, had been attending

toy shows for years and was discouraged by the lack of diversity among

dolls. “When I decided I wanted to create a companion for little

people,” Aisha says, “Mom got me into a toy fair.” They connected with

a manufacturer in China who took Aisha’s drawings and translated them

into ten-inch-tall cotton plush dolls. Since Aisha was training for her

Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine degree, her mother and father, trustee

emeritus Harold Bailey ’70, helped run the company.

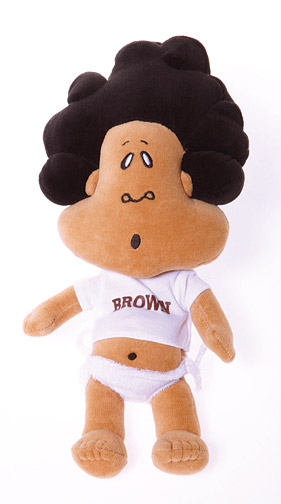

Instead of identifying her dolls by race or ethnicity, Aisha named them

by “flavor.” “I wanted them to be scrumptious and edible,” she says.

First came Turbinado Boy and Girl, then Coco, Caramel, Peach, and

Marigold. Ishababies now come in eight flavors, each with a distinctive

set of interests—Coco Boy’s a geologist, for instance, and Poppy Girl’s

an Olympic athlete.

Aisha says the most moving moment in her dolls’ creation was seeing

Mocha Girl, a dark-chocolate colored diva with irresistibly soft

Afro-puffs. Harold Bailey—who, like his wife and daughter, is African

American—told Aisha that Mocha’s skin color was too dark to sell, but

she persisted. “When I saw the first prototypes, I was in tears,” she

says.

Public response to the dolls speaks volumes about the ways children and

adults see difference. “Adults may say, ‘I want the Asian doll,’ but a

child will say, ‘that one looks like so-and-so down the street,’” Aisha

observes. “Kids want to be with kids who like the same things they do.”

Perhaps it’s generational, says Aisha, who now serves on Brown’s

President’s Advisory Council on Diversity. “Teenagers today don’t

necessarily want to be seen as black. They want to be seen as

skateboarders … or whatever.”

Still, the pediatrician in Bailey comes out when she talks about the therapeutic role her dolls can play in boosting children’s confidence. She tells the story of one of her patients, an eight-year-old boy who lived in a mostly white neighborhood with his white dad and black mom. Receiving a Caramel Boy doll, he was thrilled. He carried it everywhere, Bailey says: “He said, ‘It looks like me!’ and he started speaking up more in class.”