When Ruth J. Simmons became Brown’s eighteenth president in 2001, the world was in many ways a simpler place. That a great-granddaughter of slaves could become the first African American president of an Ivy League university seemed an event of great hope, as if Brown were somehow rising above our nation’s history of lynchings and Jim Crow laws to demonstrate the shining example that a forward-thinking university could be. Coming after the fleeting presidency of Gordon Gee, Simmons’s appointment seemed to nudge the University back on stride, reminding it who it was and what its place in the world might be.

Fortunately for Brown, Simmons arrived with transformation on her mind. Armed with the impatience and single-mindedness of a burgeoning leader, she embraced Brown’s values and history while scolding it for its timidity and complacence. Her message was simple: Brown was at risk of falling behind its Ivy League peers. To succeed, it needed focus, boldness, larger aspirations. For too long the University saw what it couldn’t do. It needed to reconsider what was possible.

Simmons started with need-blind admission, removing the ability to pay from the admission equation. It was something the University had wanted to do for years, but administrators didn’t think the place could take on the financial burden. Along with then-Chancellor Stephen Robert ’62, Simmons sat down with the budget and showed the Corporation that it could be done. Then she demonstrated her skill as a fund-raiser by closing the deal with Sidney Frank ’42 after he called to say he was interested in making a substantial contribution—eventually in the neighborhood of $100 million—to Brown. It would, Simmons realized, relieve all anxiety about Brown’s ability to afford need-blind admission.

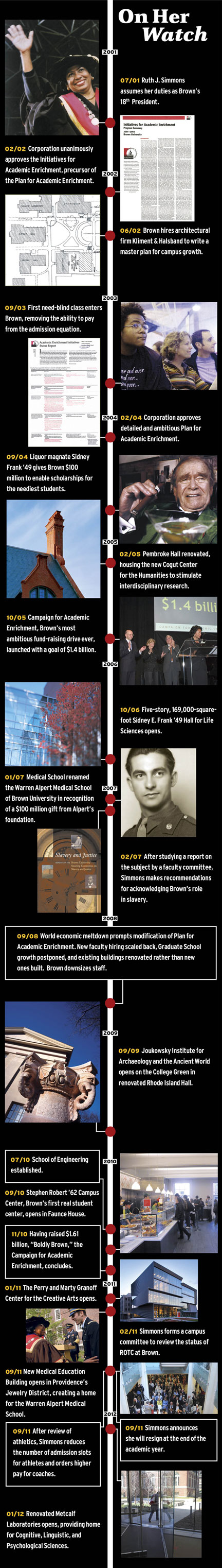

That was just a warm-up. Simmons’s Plan for Academic Enrichment was a blueprint for expansion: more faculty, more and better facilities for faculty and students, a bigger medical school, an expanded graduate school. She reorganized the Corporation, the faculty, the staff. She launched the biggest fund-raising campaign in Brown’s history, setting a goal of $1.4 billion, almost three times higher than any previous campaign. Despite the economic collapse of 2008, during which Brown lost $800 million in endowment, she beat her goal, raising a total of $1.61 billion.

But these were distractions, really. For eleven years, Simmons did what she could to browbeat, cajole, persuade, and sweet-talk Brown into seeing itself as a true university, one whose research is as good as its teaching, and one that—especially after 9/11—must not only open its gates to rich and poor students, but also ready them to compete on the international political, cultural, and economic playing field.

Shortly after Simmons was named president, she and BAM

editor and publisher Norman Boucher discussed her thoughts about the

University. Eleven years later, she sat with him again to look back

over her presidency. Here an edited version of that interview.

RJS It is not a good thing for the premier universities in this country to be seen as the province of the wealthy. Losing touch with the broad spectrum of citizens of their country, becoming isolated as institutions, is not in the interest of higher education generally and certainly is not in the interest of these institutions. So that basically means that anybody who is bright enough, capable enough, should see themselves as able to apply to, and be considered for admission to, the top universities in this country. That’s so fundamental a principle of this country that I thought it was essential to stress it.

BAM You grew up in Texas poverty. What role did your own experience play in that emphasis?

RJS I think if you’ve been

mired in poverty at any juncture and you get to know the capabilities

of the people in very poor communities, you’re the first person to

recognize that there is as much talent and brilliance in that community

as in any other.

BAM Why did you single out faculty support as your second priority?

RJS I had heard in the

transition period from many faculty and others at Brown that faculty—in

terms of compensation, leave programs, equipment, and startup money for

research projects—were greatly under-resourced and that that had

reached a critical point at Brown. Faculty were paid at lower than

market levels, which meant they could be recruited away pretty easily.

It meant that departments did not feel they could compete aggressively

for the best candidates. And this resulted in a kind of acceptance that

we should not aim for the highest-quality candidates but aim for a tier

below that. Almost twelve years later, we are still trying to build up

these resources. That’s going to be an ongoing challenge for Brown for

some years to come.

BAM One of your earliest

accomplishments was to make admission to Brown need-blind. Brown had

long wanted to become need-blind, but you got it done. How?

RJS Well, people probably

don’t realize that I don’t have the power to do those things. As

president I do a lot of advocating to the Corporation. The great fear

was that need-blind would consume the University’s resources. So I

treated it as a budget issue. What I was able to show is that there are

certain levers that we had access to in the University so that, if

need-blind became a very serious problem, we could correct for it.

BAM What kind of levers?

RJS There’s a whole series

of decisions we make about the budget every year. Some of those

decisions come with huge figures. So, what if you are four million

dollars or five million dollars over in one year? How can you address

that? Well, you can address that by doing something less in this

category or that category. I was taking the budget apart and showing

them how those kinds of things could be done relatively easily. Not

without some pain, but they could be done.

RJS One of the things I have tried to say in my time at Brown is that you cannot ignore the fundamentals. And for a time Brown tried to ignore the fundamentals. The work we have done these past eleven years has been about the fundamentals.

BAM What fundamentals was Brown ignoring?

RJS Start with Brown’s

mission and its legacy. Now here is a very unusual thing: an

institution founded during the colonial period that survives to this

day. You have to ask, “What opportunities do we have, and what

responsibilities do we have as a consequence of the fact that we are a

250-year-old institution with a certain legacy?” During our earliest

days, look what we were doing in the debate about slavery. We could

have insulated ourselves, particularly given the involvement of certain

of our incorporators in slavery. But even then students and others were

raising questions about a fundamental issue in this country: was

slavery right or not?

BAM So from the start Brown students took an unpopular stand on a moral issue.

RJS That’s an

extraordinary thing. I feel so strongly that to be doing that in that

time was an amazing thing. I understand that perhaps better than most,

because I lived through Jim Crow and know how silent people were about

dreadful inequalities in this country that today you would look at and

say were patently absurd and illogical. Yet millions of people were not

only silent but vociferously supported the idea of those inequalities.

So, during the period of slavery, students and others at Brown were

taking that position. If you go from there through the history of the

University and think about other periods in which similar kinds of

things were done, what you have to say to yourself is that

fundamentally we have a tradition, which we honor and uphold, that

requires us to do certain kinds of things. So that’s a basic.

BAM What other fundamentals did you have in mind?

RJS We are an institution

that miraculously, over 250 years, has been at the top of higher

education. You can’t purchase that. You must earn it. And therefore you

must not squander it. Squandering it is not paying attention to the

things that continue to make the University strong. And so the

university has evolved—by that, I don’t mean Brown alone has evolved, I

mean the university as a concept has evolved—and it is now a global

enterprise in which you’re educating a range of students in a range of

disciplines to solve all kinds of world problems. So now you’ve joined

to that original aim this more complex aim, which is to advance

education, research, and service to the world. You can’t turn away from

your obligations to this broader mission and pretend that you are a

colonial university, very small, very precious, very indifferent to

what’s happening around the world. So I think the basics have to do

with understanding who we are and what we must do to be the best of who

we are.

BAM And the Plan for Academic Enrichment was the strategy for doing this?

RJS It’s very difficult to

describe to people what it is that universities do. So we came up with

a comprehensive statement about what the University is doing and what

it needs to do near-term. Presenting a detailed plan was essential for

our supporters around the world to know what’s happening at Brown and

what we were aspiring to do. The whole idea of educating our alumni

about what we were doing was vital to getting the resources to do what

we needed to do.

BAM And how did you educate them? How did you make them feel included in its excitement?

RJS To me the beauty of

the Plan was to really test whether or not we were prepared to be

completely open in what we were doing. Saying we must improve the

Graduate School is a controversial issue for anybody who supports the

undergraduate program and believes that Brown should be an

undergraduate institution. Our approach was to disclose fully what we

were doing, and I think it was the right approach. Today we have a much

different alumni appreciation for what the new University is.

BAM It’s a risky strategy, particularly because you needed to raise so much money to implement the Plan.

RJS I suppose at

some level it was, but I was never one of those who doubted that we

would raise the money. And I think that’s the virtue of having someone

from the outside come in. There were lots of doubters who said, “Well,

gee, Brown will never be able to raise money at a level comparable to

other institutions, because Brown’s alumni don’t buy into this whole

fund-raising thing. They value things different from money.” Given

where I came from, I thought, “Well, that’s total rubbish.” So I never

really thought that it was a risk.

BAM What else made the Plan effective?

RJS What I’d heard about

Brown before I came was that it’s basically a place where everybody

does their own thing. They said that about the management of Brown.

They said it about the academic programs. People thought of Brown as a

kind of unplanned place.

BAM Did you find that was true?

RJS When I came to Brown

and began to meet with people—with the Corporation in particular—I saw

that it was very hard to tell who was making what decisions.

Universities by and large have great difficulty focusing and executing

in a simple way. You get very bright people who basically will go off

and build silos and do their own thing. And that’s absolutely the

challenge that most universities face, and why it’s very hard to shape

a common direction at a university.

BAM How do you address that?

RJS We needed to think

hard about accountability and responsibility for certain specific

things. And we started first with the Corporation, because the

Corporation was a tad more social than it needed to be. I remember one

of the early things I said to the Corporation was, “If Brown is not

what you think it should be, then you’re directly responsible for that.

And if the faculty salaries are not what they should be, you are

directly responsible for that.” At the same time, I would say I’ve been

very lucky to have a Corporation that has been tremendous. I’m very

much aware that many presidents can’t say that.

BAM How did you deal with the everybody-doing-their-own-thing culture?

RJS I knew that if people

continued to do their own thing we would never get where we needed to

go. So the Plan was intended to keep all of the units on the same

script and to hold them accountable. It provided a central narrative

telling us where we were going and how we were going to get there.

BAM As I recall, you also encouraged more decision making.

RJS We started on campus

with the faculty governance system. We decided to incorporate students

on a lot of committees. We brought staff onto committees. The deal was

to give people participation, to fully disclose what’s happening, and

to really make it work in an authentic way, not just by dictating to

people what should happen.

BAM I would think that process would slow things down.

RJS Doing that has really

meant that we take more time to make decisions than many people think

we should. But if you were to ask where we ended up as a consequence of

taking things through that process, I’d have to say for the most part

we inevitably ended up in a better place because we took the time to do

that.

BAM So you came up with

the Plan to, among other things, expand the faculty, broaden the

medical and graduate schools, build new facilities on campus—and the

financial meltdown of 2008 hits while you are trying to raise money for

all these things. How did you cope with that?

RJS We always have to

proceed from the vantage point of core principles. What I argued with

the Plan was that its core principles should serve us in good times and

bad times. Before there was even a hint of the financial meltdown, I

argued that the Plan was best designed and best understood to be the

greatest protection the University had in a severe downturn or a severe

crisis.

BAM What does that mean?

RJS It means we understood

immediately that we would not have to sacrifice the central priorities

we had set in the Plan. We would do it around the margins, but never at

the core. We protected faculty resources. We protected our hiring of

faculty. We protected the financial aid budget.

BAM What were some of the things you couldn’t do because of 2008?

RJS There were new

buildings that we were going to build, and we asked ourselves if we

could achieve this same goal differently. We were going to build a new

medical school building, for example. We were going to build a new

building for cognitive, linguistic, and psychological sciences. We went

back and looked at those projects and said, “Wait a minute. Let’s

rethink this. Maybe we can renovate Metcalf at half the cost.” That was

very tough. When we had to say to that department that you’re not

getting your new building, they were none too happy.

Same with the medical school. We decided to take a building and

renovate it instead of building a new one. So it isn’t that we didn’t

do certain things. It’s that we did them differently. We economized.

Unfortunately, we did downsize at that time. We tried to do that in a

way that would be far less painful than what we saw happening on some

campuses.

BAM As you look back, is there anything about the Plan that you would do differently?

RJS No, I can’t say that

there is. I could have done a lot more if I had been willing to settle

for more top-down decisions. I think most presidents, frankly, would

have done that. We could have moved a lot faster. I’ve been very

frustrated the last few years because during my first year at Brown I

said, “Gee, we really need a student center.”

I think it was probably during my first two years that I said we needed

a fitness center. Early in my presidency I said we need an overhaul of

the dormitories, but we’re just getting around to that now. By setting

up an inclusive process, you do sacrifice getting some things done in a

more timely way.

BAM Were you frustrated by the pace of change at Brown?

RJS I always say you have

maybe a handful of things you can do in this kind of environment. Had I

been president of another university, one accustomed to a different

kind of leadership, there’s no question that I would have done more.

Other communities would have been more amenable to presidential power,

but my reading of this community was that it was not. Still, I am

pretty satisfied with the things we managed to get done.

BAM You set up a committee

to look at Brown’s role in slavery and whether the University should do

anything today to acknowledge that role. What’s your assessment of the

committee’s recommendations?

RJS My reaction when I got

the report was that it was more ambitious and much broader than I

expected it to be. I actually thought it was the wrong approach to have

such a laundry list of items. I thought it should be somewhat more

focused. My greatest concern was that this would be the kind of report

that sat on the shelf and a very small number of people would actually

take the time to read.

BAM What struck you as unrealistic?

RJS We spent a lot of time

talking about an apology from the University. That was one of the

stickiest points. Some members of the committee thought it was very

important for the University to issue an apology. I must say I’m not a

fan of apologies. I think they are rather superficial. People tend to

issue apologies and then move on. And I thought that was unworthy of a

process that had been so deep and expansive and important in the

history of the University. I thought history ought to reflect not

something singular, like the headline “The University Apologizes for

Its Ties to Slavery.” The question for me was: what was there of

lasting value that we could hold up to the world as indicative of the

kind of process one could undergo in reconciling oneself to past wrongs?

BAM How would you assess the implementation of those recommendations?

RJS In the main I believe

we have done well with the implementation. For example, we set up the

program for teachers in the Providence schools. We’re going to have on

the front lawn of the University a sculpture done by a leading African

American sculptor that is going to be a recognition of slavery. That is

going to be probably one of the most lasting elements of this. That’s a

very visible statement.

BAM Did the slavery and justice committee have a particular resonance for you as an African American woman?

RJS I can tell you that,

out of all the things I’ve done, that’s the thing I hear about the

most, which is very bizarre to me because I don’t really see it as a

particular mark of my time at Brown. But if I am in another country,

it’s something people know about. It’s rather ironic.

BAM A big emphasis of your presidency has been internationalization. Why is this important?

RJS Our competitors are

internationalizing at a much faster rate than we are. As a consequence,

they are making themselves more attractive on the global stage. Also,

future alumni will live and act in a more global environment, and to

the extent that the University is not profoundly international, they

will be at a substantial disadvantage.

BAM Are you happy with the pace of internationalization at Brown?

RJS I think we are not moving fast enough. I believe our efforts have got to be bigger and much more far-reaching than they are.

BAM What would success look like?

RJS It would include more

institutional partnerships. It would look like having many more

resources for our students to be able to have international internships

and experiences. It would mean taking advantage of opportunities to

have outposts in different parts of the world. I think there is nothing

whatsoever wrong with having, for example, an outpost in

Mumbai—something on the ground that carries Brown’s message in India—or

having an outpost in Beijing. Compared to our peers, we are much more

domestic. I think what this causes over time is a sense that we are a

small place that is not keeping up with the direction of our knowledge

and the direction of this global reality.

BAM Why haven’t we been able to internationalize faster?

RJS Resources. I expect

we’ll see more effort in this area under President Paxson. It’s

obviously an area that she is familiar with.

Let me say how much work has been done on this already. For example, we

created these international advisory councils, and the India advisory

council has been wonderful in advising us about what to do in India.

We’ve had a similar situation with China, and we’re trying to start an

advisory council for Latin America.

The travel is unbelievable. Every president of Brown is going to spend

a significant amount of time traveling internationally, which

complicates the job, obviously. But most university presidents today go

out around the world numerous times in the course of the year, and they

spend a lot of time away from their campus. So one of the things the

University has to deal with is the necessity of presidents today to

spend significant blocks of time away from campus just on the

international piece.

BAM While other Ivies have

received attention for inviting ROTC back to campus, Brown chose

another route. How do you respond to people’s confusion about the

University’s position?

RJS The way I characterize

this issue is that, when it comes to such matters as loyalty to the

country and service to the nation, there should not be a narrow litmus

test. In much of the debate about ROTC is the question of whether or

not every institution, in order to demonstrate that it’s doing its

appropriate service to the country, must have ROTC. I think that

argument is quite ridiculous, frankly.

BAM So what should Brown do?

RJS It’s important for

Brown to have some link to those who serve in the military. I agree

with that. What I disagree with is whether that should be fixed in

terms of how Brown should accomplish that. In my view, as long as Brown

understands how vital it is to support the interests of any students

who wish to have careers in the military, it can do its service to the

nation by doing that. I don’t think that the symbolism of a unit on the

campus is all-important.

As an individual, I have a very emotional reaction to this. I have two

brothers who served in the Korean War. One was almost killed. At a

basic level, I’m offended by people who feel that they can have others

go off to give their lives while they hold no responsibility for

supporting the policy or programs that make it possible for people to

go off and do that. The one thing I said to students when we declared

war on Iraq was, “You must not go back to your rooms and be satisfied

that there’s a war going on and there are people giving their lives and

it does not concern you. That does concern you, and the one thing you

must do is stay involved in this.” I feel very strongly about that.

BAM You have been

president during a powerfully historic time. How have the changes in

the world over the past eleven years changed Brown—and you?

RJS I’ll never forget 9/11

and the way that horrible event descended on all of us, on our psyches,

on our sense of security, on our sense of humanity. It was breathtaking

to recognize what that could mean about the state of the world and

about the way Americans might be perceived in the world. That was just

a startling, startling thing. It’s changed our lives so completely.

As deeply unsettling as that was, every year when I welcome students to

Brown I see the absolute joy and the hopefulness of generation after

generation of young people. I feel sorry for people who don’t have that

in their lives, because you cannot know how absolutely hopeful you can

be until you see every year the way students continue to come along and

believe that there’s something extremely important they can do to

rescue humanity from itself. And we see it all the time and it is the

most powerful thing.

So in what way has it changed me? It’s just that during that period of

time when we’ve seen some of the very worst of human behavior, we’ve

also seen some of the best and most promising human behavior. That

allows us, encourages us, in our work to just keep making access to

education the most important thing that we bring to the world.

I think about the Israeli student who came to Brown and reached out to

Palestinian students on campus to try to bring about a serious and

healing conversation about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. We will

not be able to do it in public policy, we may not be able to do it

through governments, but you know that, because this is happening among

young people still pushing forward and trying to solve these problems,

they’ll be more successful at it than we have been. That’s been a

tremendous gift in the wake of these kinds of events.

BAM You’ve been able to keep up relationships with students?

RJS One of the best things

about my eleven years has been my open office hours. It has been

heartening to me that students are willing to come and talk to me about

their projects and their solutions to world problems. It’s impossible

to be in an environment like this, where students are doing that,

without feeling that despite heinous acts that can bring us to the

point of despair, there are also the most uplifting acts that can bring

us to the point of hope. Steve Robert, the former chancellor,

established a foundation in his retirement, and, when I first saw the

name of it, I thought how striking and wonderful it was. The name of

the foundation is Source of Hope, and what he and his wife, Pilar, aim

to do is to identify projects in countries, like Ethiopia, that offer

hope. And I think in some way this reflects what Brown is really all

about, that source of hope.