At the end of the 1961 school year, the Brown Daily Herald staff gathered at their campus office for an end-of-the-year cleanup. Shelves were emptied, half-filled food containers finally thrown out, and a semester of stray newspapers dumped in the trash. Among the stray items rounded up from one shelf was a reel-to-reel tape, a recording made by a local radio station of a speech given by Malcolm X on campus several weeks earlier.

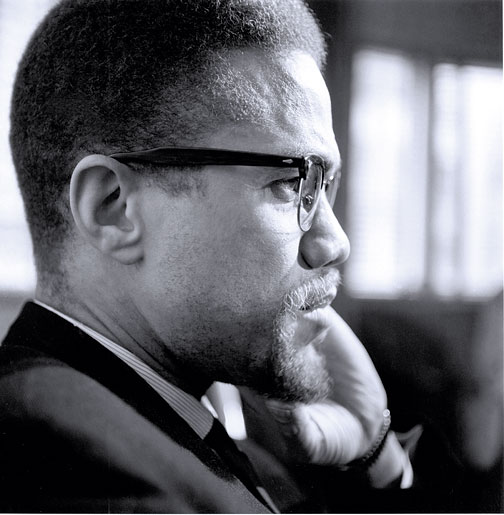

This January, Malcolm Burnley ‘12 was in the John Hay Library leafing through a binder of old Brown Daily Heralds. Burnley was looking for a subject for a paper he’d been assigned in his nonfiction writing class. When he spotted a photo of Malcolm X in one issue of the BDH, he paused. The article accompanying it noted a speech the Black Muslim leader had delivered in Sayles Hall before an overflow audience of 800 to 900 people.

Burnley had no idea that Malcolm X had ever been to the University, and

the idea intrigued him. He began looking for other stories in the BDH

about Malcolm X and soon found one. It was a long, highly critical

essay on Black Muslims. Malcolm X had come to Brown to rebut it. And it

was written by Katharine Pierce. It was at this point, Burnley says,

that what had started as a project he’d stumbled into began

“snowballing and snowballing. It became an unbelievable story.”

Pierce grew up in Connecticut and attended the George School, an

elite Quaker boarding school outside Philadelphia. She hadn’t had much

exposure to African Americans. But at Brown she majored in anthropology

and sociology and found herself fascinated by religion. In the fall

semester of her junior year, she took a class on Islam. It was her

professor, Horst Moehring, who suggested to Pierce that she write about

the Nation of Islam (NOI), the Black Muslim group that had been around

for thirty-one years.

Pierce liked the idea. Along with the rest of her family, she was a

liberal on the subject of civil rights. Even at this early point in the

civil rights movement, Pierce staunchly supported integration. The NOI,

though, took a more radical position, arguing in favor of Black

Nationalism and the separation of the races. Just a few months earlier,

in February, the group had been part of a messy demonstration inside

the United Nations that thrust them into national prominence.

Pierce avidly pursued the project. Not content with library research, she visited the group’s temple in Providence and gathered fliers from a rally it had staged in New York City. She and her father attended a production of Orgena, A Negro Spelled Backwards, a three-hour musical written by future NOI leader Louis Farrakhan. Pierce remembers that the show, staged at Carnegie Hall, depicted the white man “as the devil.” She and her father were the only whites in the audience. People stared at them. She heard someone whisper, “What are they doing here?” But Pierce suspects that most people simply assumed no white person would ever come to see such a show. “I think they thought we were black,” she says. “They just thought we were really light-skinned.”

In the paper for her class, Pierce described the NOI as a “cult,”

arguing it was full of “agitators” who advocated “irrational solutions”

to the problem of racism. It “was a subversive type of organization and

one which could be very dangerous,” she continued. The NOI’s philosophy

ran counter to Pierce’s liberal views on integration. The black slave,

she insisted, “was stripped of his name, religion, and language….He

became naked, as it were, and his only hope of being clothed came from

his superior master.” Nonetheless, she said, the NOI was a group that

had “misdirected its energy, and they need to be shown the value of

constructive work which is being done to advance their position.”

The paper drew the interest of one of Pierce’s religious studies

classmates, who also happened to then be dating the editor of the BDH,

an energetic young man named Richard Holbrooke, soon to become one of

the country’s great diplomats. When Holbrooke ’62, who died in 2010,

learned about Pierce’s essay, he asked if he could publish it.

Flattered, she immediately consented. “Richard,” she says, “had quite

the eye for a story.”

Holbrooke and Pierce struck up a friendship that soon led to listing her as the first woman ever on the BDH

masthead. Not that anyone would know. Holbrooke listed her as “K.C.

Pierce” to disguise her gender. Pierce says he was worried there’d be

an outcry if it became known the BDH had a high-ranking female

editor. As for her title, Pierce says, “He didn’t know what to call

me.” It was listed under her name as a string of question marks.

Shortly after the BDH published Pierce’s piece about the

NOI, Holbrooke’s phone rang. On the other end of the line was a

representative of the NOI who wanted to know if Malcolm X could give a

speech about the group on the Brown campus. Somehow Pierce’s article

had made it all the way to the Black Muslim leader.

Holbrooke, of course, loved the idea. But it took six visits by Holbrooke and Pierce to President Barnaby Keeney’s office to convince him to let Malcolm X enter campus. Keeney was worried about security. He also knew that among the schools that had refused entry to Malcolm X were UC Berkeley, where the Free Speech Movement was about to begin, and the historically black Howard University. On the other hand, as Holbrooke and Pierce were quick to point out, Harvard and Yale had let Malcolm X talk.

In the end, Keeney agreed to allow Malcolm X to come to campus on May 11—provided the BDH picked up all related expenses. To help cover its costs, the newspaper charged fifty cents a ticket. The NOI provided its own security. Pierce remembers that the crowd included about 200 Black Muslims who had driven down from Boston. Pierce believes the rest of the crowd came from outside Brown. The University at the time was still a relatively conservative place. The campus, she notes, was “not particularly excited about my article.” In fact, she recalls, race rarely came up in conversation.

But, for the people gathered in Sayles Hall that day, the event was one to remember. Pierce still calls the speech “riveting.” “Like everybody else there I was absolutely captivated by the brilliance of the man,” she says. “We were more impressed by the man and his delivery than by all of the specific points he made.”

Soon after Malcolm Burnley first read Pierce’s BDH article, he visited her at her home in Nyack, New York. She told him the story behind Malcolm X’s visit and recalled her friendship with Richard Holbrooke. She described how she’d given some introductory remarks before Malcolm X spoke and then was whisked offstage immediately after his speech for fear that someone might attack her. The BDH later interviewed Malcolm X at the Providence Biltmore Hotel, but only the male editors went. It was judged too dangerous for a woman. Pierce may have been the reason for Malcolm X’s visit to Brown, but she never got to meet him face to face.

Almost as an aside, Pierce asked Burnley if he’d heard the speech. Burnley said he didn’t know how this would be possible. There was a tape recording, Pierce explained. She’d taken it with her after graduation. Every time she did a spring cleaning over the years, she would open the box it was in and think that maybe it was finally time to throw out the tape. She got rid of other college memorabilia, but was never quite able to part with that tape. “Somehow,” she says, “it struck me as too precious to throw away.”

In 2010 she’d at last unburdened herself of the tape by donating it to the John Hay Library. She told Burnley that, as far as she knew, it should still be there.

Burnley found it a few days later. It sat, uncatalogued, gathering dust on a shelf. He’d pored over the many biographies and histories dealing with Malcolm X and had never found more than a passing mention of a speech delivered at Brown. Then, as he listened to the tape, he realized he’d unearthed a lost treasure, a speech that no one had listened to in nearly half a century. “It was really like stepping backwards in time,” he says.

On the tape Burnley heard Malcolm X lay out the case for separatism as the only path to empowerment and freedom for blacks. “No,” Malcolm X said that night, “we are not anti-white. But we don’t have time for the white man. The white man is on top already, the white man is the boss already.… He has first-class citizenship already. So you are wasting your time talking to the white man. We are working on our own people.”

What struck Burnley about the speech was its relatively moderate tone. Other Malcolm X speeches from around the same time struck Burnley as more radical. But the speech at Brown took a more positive approach, emphasizing the virtues of Islam and how it had saved Malcolm’s own life.

“We are taught, as Muslims,” he told the crowd, “never to be the aggressor, never to look for trouble, to always seek peace.” He drew a gasp from the audience when he detailed his criminal past, but he said the teachings of the Nation of Islam “stopped me from doing these things overnight.”

Malcolm X officially broke away from the NOI two years later, in 1964, but Burnley believes the speech shows him already moderating his views. “I discovered a little wormhole into Malcolm’s life that’s pretty cool,” Burnley says.

As for Pierce, she was bombarded by calls from the press after word leaked out to the media this winter about Malcolm X’s long lost speech. Pierce, who’d spent the early part of her career as a social worker, had for the past twenty years been working as a private consultant designing computer training programs. She’d been working out of her home, far from the limelight, when the publicity storm around the Malcolm X speech found her. “I’m absolutely aghast,” she says. “It’s exhilarating and fascinating. It’s the time of my life.”

Lawrence Goodman is the BAM senior editor.