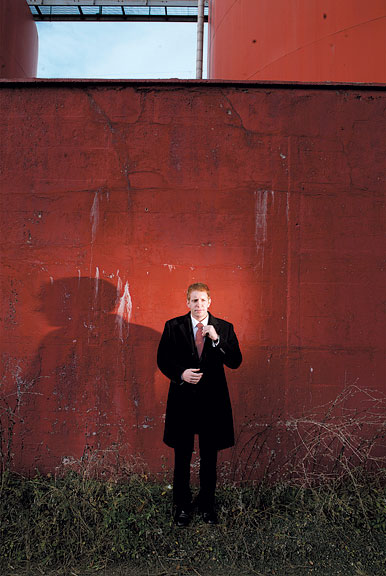

It was an unusual reaction for a politician just elected to public office. A seasoned veteran likely would not have revealed even a hint of surprise at winning. But when Alex Morse ’11 learned in November that voters had chosen him to become mayor of Holyoke, Massachusetts, he seemed taken aback...

It was the unpolished—some might say, refreshing—response of a very young man new to public office. Six months earlier Morse had been sitting out on the College Green listening to President Simmons congratulate his class for having made it through college. An urban studies concentrator, he had grown up as the smart and driven youngest son in a working class family, and his studies at Brown had helped him focus his attention on the future of his hometown. And now here he was at age twenty-two, the youngest Holyoke mayor ever and the second youngest in the history of Massachusetts.

"This is an incredible moment," he continued on election night, "not just for this campaign, but for the city of Holyoke. This has never been about me.... This has always been about the future of Holyoke."

But, in the days following his election, the story was very much about him, about the Brown kid whose first job out of college was mayor of a troubled New England city. The CBS Evening News devoted an entire segment to Morse's story, and, among others, MSNBC, the Boston Globe, and the Christian Science Monitor quickly followed. Alex Morse's fifteen minutes of fame reached as far away as India and China. President Obama even invited him to the White House holiday party.

And then all the fuss died down, and Morse was left facing the difficult challenge of revitalizing a small industrial city left behind by the twenty-first century economy. In many ways the story of Holyoke is similar to that of many small cities across the United States that struggle to remain solvent in the face of rapid change—except that its rise and fall may have been more dramatic than any of them. In 1900 Holyoke had the largest number of millionaires per capita of any city in America. One of the first planned industrial municipalities in the country, by the mid-twentieth century Holyoke—Paper City—was the nation's leading paper producer, its mills powered by an elaborate canal system that diverted water from the Connecticut River.

And yet Alex Morse has spent the last few years of his life wanting nothing more than to become Holyoke's mayor, a position that pays $85,000 a year. His optimism about the city's future is startling. "Holyoke has tremendous possibility and potential that is untapped," he says. "I wanted to help find it and realize it." To do so, Morse defeated the incumbent, Elaine Pluta, the city's first female mayor and a former congressional aide who also spent fourteen years on the city council before becoming mayor.

To hear Morse tell it, deep political experience is more of an obstacle than an asset when it comes to solving Holyoke's problems. People in the city, he says, have become tired of the "same old problems" and the same political faces. "Voters saw my age as an asset," he says, as someone who sees the world with fresh eyes and a more modern perspective. As a political neophyte, Morse boasted that he is "not beholden to any political interests" and is not "tired or discouraged." Instead, he offered optimism, youthful energy, and, perhaps most important, a vision for the city that his predecessors lacked.

Throughout the campaign, Morse repeatedly differentiated himself as "the only candidate raised in the digital age," one who could best understand and capitalize on opportunities to grow an emerging high-tech sector in the city. Morse expertly used such social media tools as Facebook, Twitter, Vimeo, and Tumblr to get his messages across, something that complemented his more traditional grassroots campaign, which canvassed the city over many months talking about the possibility of a new, revitalized Holyoke.

"People here want to see the city move forward and are ready for change," says Timothy Purington, a former city councilor and one-time Pluta supporter who endorsed Morse in the November election. "Alex was able to articulate his vision, and it resonated with people."

In the election, Pluta argued one of the city's best bets for job growth was a controversial casino proposal. Morse, on the other hand, presented a menu of ideas for retaining businesses in Holyoke while attracting new ones. He plans to reduce the regulatory hurdles incoming businesses and developers face and to provide tax incentives for existing businesses that expand or renovate.

"At this exciting juncture," Morse says, "we need a mayor who can be a chief marketing officer. We need someone who can take advantage of the High Performance Computing Center and market Holyoke as the art and technology hub of Massachusetts."

Morse has also articulated a plan for improving Holyoke's schools. As mayor, he will chair the city's school committee. He hopes to create a citywide core curriculum, as well as a program for gifted and talented students. He has plans to revitalize Holyoke's ailing vocational school by improving technical training in "green" occupations and by strengthening its connections with local businesses so that vocational students will have more opportunities for internships and apprenticeship programs.

"I plan on asking the business community for their help in turning our schools around," he says. "Holyoke gave me the opportunities I have today, and I couldn't leave the city until every child in Holyoke has the same opportunities that I had."

The best example of the kind of success Morse has in mind is the mayor himself. The child of two high school dropouts—his mother, Kim, later earned her GED and an associate's degree—Morse is a product of the city's struggling public schools and is the first member of his family to earn a bachelor's degree. He has two older brothers, twenty-nine-year-old Matthew, a delivery driver, and thirty-one-year-old Douglas, who has worked in roofing and construction but is now unemployed. Neither sibling attended college, but Morse says they both want to return to school.

For Alex Morse, the educational journey that eventually led to Brown began in Head Start, the federal preschool program for low-income children. Morse's parents taught him to value the education they were not fortunate enough to get, he says. And when it came to working hard, they taught him by example. His father, Tracey, began in an entry-level job in the shipping department of a local meat plant and worked his way up to transportation manager. Morse says his father rarely missed a day of work. His mother, Kim, ran a successful home daycare center while raising Alex and his two brothers. She returned to community college in her forties and became a licensed practical nurse, realizing a lifelong dream.

Morse says that, while his upbringing might be considered modest by some, his family was not poor. By the time Morse was born, the family owned a single-family home and his parents had more resources and time to devote to him and his education. "Because I am the youngest child, my parents were able to provide me with a great childhood, and they had the economic means to do so," he says. "My parents have worked hard their entire lives to provide me and my brothers with the opportunities that they didn't have growing up: vacations, college, a nice house, a pool."

Despite the problems in the Holyoke public schools, Morse says he got an excellent education and had committed, talented teachers. His mother, who also had a great influence on him, was the type of mom who baked cupcakes for every school event, chaperoned on field trips, volunteered in the classroom, and, perhaps most important, constantly communicated with her son's teachers. Morse's parents encouraged him to go to college and told him he could be whatever he chose to be in life. "They were number one to me," he says.

But Morse says his drive and ambition also came from within. "I was an incredibly motivated student from a young age," he says. "I always challenged myself to be the best, and I wanted to make my family proud. I wanted to win every award and get the best grades." Recognizing that he was academically gifted, teachers gave him special attention and extra work over the years to make sure he wasn't bored.

Morse also took an interest in politics as a boy. He closely followed the 2000 presidential election and was bitterly disappointed when it was ultimately settled in favor of George W. Bush instead of Al Gore. Morse's parents used to joke that instead of kids' shows, their precocious son watched CNN. At age twelve Morse joined the Holyoke Youth Commission, which met at City Hall and advised municipal leaders on issues affecting young people. Morse says he was "hooked" on politics from that point on.

Going through the public schools was also an education in diversity. It opened Morse's eyes to Holyoke's social and economic class differences. He saw classmates who didn't have coats, hats, or gloves in winter, or enough food to eat. "I realized that some kids were poorer than others, some had things and others didn't, some lived in nice houses and others didn't," he says.

As a teenager, Morse's talent for leadership emerged. He became president of the citywide youth commission and in his final two years at Holyoke High School was the student representative on the city school committee. He was salutatorian of his graduating class. He founded the high school's first-ever Gay Straight Alliance and then went on to create a similar citywide organization that over the past five years has organized an annual pride prom for gay, bisexual, and transgendered students in the region. Morse, who is publicly gay, says he was upfront about his sexual orientation during the mayoral campaign, but it really never became an issue.

Morse's own coming out as a young gay man at age sixteen was a "refreshing" process, he claims. When he told his parents he was gay, he says, their response was "incredibly loving and accepting." He was one of the first gay students to ever come out at Holyoke High, he says. "My constituents know that I am gay," he says, "and respect me for my honesty, integrity, and courage."

Morse first thought about running for mayor of Holyoke while he was still in high school. By the time he entered Brown, he was actively thinking about how to turn things around in his hometown. Morse has said he was not entirely comfortable with the wealth and privilege he encountered at Brown, but the University gave him the opportunity to study urban issues with such top scholars as Marion Orr, Hilary Silver, Patrick McGuigan, and Kenneth Wong.

Morse says it was at Brown that he learned how to look beneath the surface at urban issues. He also studied how other cities have addressed problems like those Holyoke faces. Morse recalls a graduate-level class with Wong in which students were able to formulate recommendations on education reform and present them to the Rhode Island commissioner of education. In a class with Orr, Morse played the role of a developer in a mock development proposed for a fictitious city, and in a class with McGuigan, he learned about the Providence Plan, a local nonprofit that works with elected officials to implement sound public policy and provide data to government agencies.

"Brown was the perfect opportunity for me to network and work with local and state officials," Morse says. "The city and state are small enough that you can actually set up meetings with high-level officials in a matter of days. And in Providence I got to witness firsthand a city that had turned itself around."

Morse says his modest upbringing in a small, economically depressed city also gave him a unique perspective in urban studies classes. "I was able to take what I learned at Brown back to Holyoke, and bring my life experience from Holyoke directly into the classroom," he says. "It was a great synergistic combination that ultimately prepared me to become mayor of my hometown."

While at Brown, Morse also interned for David Cicilline '83, who was then mayor of Providence and is now a Democratic U.S. Congressman. For Cicilline, Morse fielded calls in the division of neighborhood services, listening to constituents complain about everything from trash collection to the public schools. "From the very beginning," Cicilline says, "it was clear to me that Alex was incredibly bright and he deeply loved Holyoke. One of the first things he talked about was his hometown and his eventual interest in running for mayor. He was mature beyond his years. It occurred to me that maybe he did not even need a mentor."

Former city councilor Timothy Purington, who also is gay, first met Morse when the teenager organized the diversity training at his high school. "I was very impressed with Alex from the moment I met him," Purington said. "Early on, it was very clear that he was quite smart, ambitious, clear-minded, and had a great ability to set his eyes on a target and achieve it."

Morse was still a senior at Brown when he launched his mayoral campaign. Even during his years on College Hill, he shuttled back and forth between Providence and Holyoke, where he worked at a career center helping young people develop job skills and find employment. Morse was still involved with numerous other civic organizations, including a Latino scholarship association, a community land trust, friends of the public library, a literacy coalition, a mental health advisory board, and a group combating the city's high dropout rate.

"What really impressed me throughout the campaign," Cicilline says, "is that he had a clear vision of what he wanted for Holyoke. These were well-thought-out and well-researched decisions about economic development, school reform, and revitalizing neighborhoods."

"He worked it, he really did," she says. "He went through neighborhoods that no one had paid attention to and talked to people who had been ignored for many years. He took nothing for granted."

Morse set up a separate Spanish website and made sure his campaign materials were also available in Spanish. He distributed signs and buttons reading "Morse para alcalde (Morse for mayor)." At public meetings he insisted on the presence of translators. When they were not available, he filled the role himself. When he made important speeches, including his victory speech, Morse spoke first in English and then in Spanish. Morse promises that after taking office in January he will create a Holyoke Latino Commission to advise him.

"When people heard him speak Spanish, there was an immediate connection," Lebron-Martinez said. "It will be a big plus for him as mayor. He can communicate with a large part of the city's population. This is going to be a new era for the Latino community."

Despite all the attention he paid to Holyoke's Hispanics, Morse says he truly is "the people's mayor." In order to beat the well-connected and familiar Pluta, he had to appeal to voters in every community, from the elderly eagerly awaiting the completion of a new senior center, to the proud Irish Americans who have dominated Holyoke's politics since their ancestors moved to the city for mill jobs, to the younger, progressive newcomers moving into Holyoke from cities and towns where houses are becoming prohibitively expensive.

Morse marched in both the popular annual St. Patrick's Day Parade (billed as the second largest in the country) and the much smaller but equally boisterous Puerto Rican Day parade. Pictures of him in both parades hang in his campaign office: in the St. Paddy's parade he wears an Irish knit sweater, green shirt and tie, while in the Puerto Rican event he is waving the island's flag.

The day after the election, Morse was up early, back to work in his campaign headquarters, which had been turned overnight into a makeshift mayor's office. He has spent the weeks since the election busily carrying his momentum forward, attending a training workshop for Massachusetts's new mayors, meeting municipal department heads and public safety officials, reading to kids in the public schools, attending a national mayor's conference at Harvard, and shopping around town for a new apartment. Not surprisingly, Morse will rent a loft apartment in a redeveloped mill building downtown. Soon, he will trade in his mom's old Buick for a new car that the city provides to each mayor.

In keeping with what he sees as Holyoke's digital future, he considers one of his first orders of business to be making City Hall completely wireless. He also extended an olive branch to his former opponents, hosting a "Unity Breakfast" that, he says, brought 300 people from different segments of the city together. He also recently held a "transition conference" to seek input from "regular people" about everything from public safety to the schools to business development and a green economy. About 170 people of all ages and backgrounds participated in that conference.

"This campaign brought a new sense of community engagement to Holyoke, and our task now is to make sure we convert this energy over into the mayor's office," he says. "This is the first time a mayor-elect has directly involved people in this transition process, and I will continue this spirit as mayor as I make decisions." Morse's friend and his future director of community engagement, Talitha Abramsen, said the campaign has energized Holyoke citizens of all political stripes in a way that no one ever anticipated. The Morse team wants to tap into that new excitement.

Even Morse's fifteen minutes of media fame were put to good use. Reporters may have thought they were talking to a mayor who is still wet behind the ears, but what they got was Holyoke's new chief marketing officer. "This puts a positive light on the city of Holyoke more than anything else has in many years," he says. "I will take advantage of every moment I can if it will benefit the city. I have already begun to change our city's perception and tell a new story of Holyoke." He even got a chance to give President Obama and the First Lady an earful at the White House party.

"It was an incredible honor to walk the halls of the White House and represent the city of Holyoke as I met President Obama and Michelle Obama," he says. Morse adds that the president joked with him, asking if he is an "overachiever." Morse invited the first couple to visit Holyoke.

In our leadership-starved political landscape, political parties are always on the lookout for the national stars of tomorrow—think of Louisiana's Republican Governor Bobby Jindal '92, for example—with mixed results. Before Morse even took office in January speculation arose that the mayor's job would merely be a stepping-stone to higher office. Cicilline, for example, noted that the Democratic Party "would be wise" to shepherd this bright political up-and-comer.

But Morse insists he wants to be Holyoke's mayor for the next eight years, if not longer. "In ten years," he says, "I want Holyoke to have a thriving downtown with cafés and restaurants, with more young people and students interacting and living there, with less crime, with historic buildings restored, a new public library, a renovated Victory Theatre attracting people downtown with new shows, and with passenger rail service bringing people to and from Holyoke." He wants the city's high school graduation rate to rise to at least 80 percent, and wants to bring the third-grade reading-proficiency level from 21 percent to 85 percent.

These are ambitious goals, as Morse and his supporters concede. But with the citizens of Holyoke behind him, the indefatigable Morse believes anything is possible.

"I want City Hall to become the people's building," he says, "where people always feel welcome, a place where people share ideas and are working for a common vision."

But first, it was time to party. In addition to planning a $75-per-ticket traditional black-tie inaugural ball, Morse, who turns twenty-three in January, also decided to hold a different "inaugural bash," a community dance party in the same mill complex where he will rent an apartment. Morse said he planned this $20-per-ticket event "to be more inclusive" and because he recognizes that many people—including his twenty-something peers and friends—can't afford the pricier inaugural ball.

Sandra Dias is a freelance writer based in Holyoke, Massachusetts.