This year marks the twenty-fifth anniversary of the only Ivy League championship a Brown basketball team has ever won. [Ed. Note: This is incorrect; Brown's women's team had amassed 6 Ivy League titles as of the time this article was published.] The first-place league finish was the culmination of an unlikely season in which the Bears' overall record was 16–11. But this is not a story about that championship run. This is a story about the game that followed. As Ivy champions, the 1985–86 team received a berth in the NCAA championship tournament, the famed road to the Final Four. Leading up to the event, the Bears were boosted by pep rallies on campus, interviewed repeatedly by local media, and were even featured in Sports Illustrated. No one expected Brown to do well during March Madness, and when the Bears faced the Syracuse Orangemen at the Carrier Dome on March 13, things went pretty much according to script. All but one of the Orangemen starters, after all, would end up playing professional basketball in the NBA or in Europe. The team was seeded second in the East region. Brown didn't stand a chance, really. The final score was Syracuse 101, Brown 52. Any other team might have found the game humbling—Syracuse scored almost twice as many points as Brown—but the Bears, who had played loose all year, laughed their way through the blowout. "We went into it with sadly realistic expectations," says Patrick Lynch '87, a small forward on the team. "But because of that, we just had fun. We celebrated—we had a knack for doing that anyway."

And so the game was also about the stark contrast between the meaning of March Madness to the schools with the big, deep programs and to the teams who go into it knowing they don't really have a chance. Miracles do happen during March Madness—in 1986, in fact, LSU tied for the lowest-seeded team ever to reach the Final Four—but they are rare. The pressure on the top-seed teams is immense, and the game sometimes doesn't seem like much fun to players from whom championships are expected. To the 1986 Syracuse players, the NCAA tournament meant serious business. Basketball was central to their lives. Of the ten Syracuse players whose jerseys have ever been retired, three were on the court against Brown that day.

"It was clear that no one on our team was going to the NBA," says center Jim Turner '86, the star of the Brown team that year. "Myself and several others went on to earn MBAs. A couple of guys became doctors. But no one was going to the NBA."

This is a look at the starting players in that game and at what has happened to them in the twenty-five years since they matched up on national television. If the starting lineups were to be read today, Brown's would include a former state attorney general, the president of two companies, and executives in the financial, insurance, and energy industries. Syracuse's would include four former professional basketball players, some with successful careers and others with disappointing ones, and two high school coaches.

What unites all of them is their memory of the game they played together in March 1986.

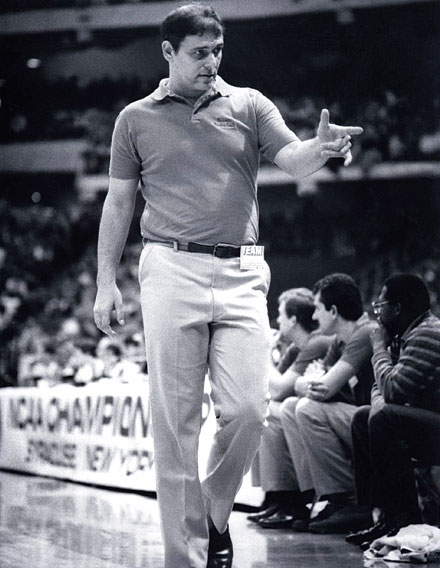

The Coaches

Even in the most prominent game of his coaching career, Bears head coach Mike Cingiser '62 wasn't concerned primarily with winning. "Yeah, we would have loved to win the game," Cingiser says. "But we all—myself and the players—all made sure we enjoyed the ride."

For Syracuse's Jim Boeheim, on the other hand, the Brown game was the first obstacle on a long journey he hoped would end with an NCAA title. Back then, Boeheim wasn't the college-coaching giant he's become today. In the twenty-five years since the tournament contest against Brown, he has won his 800th game, taken three teams to the Final Four, won a national championship, and been inducted into the National Collegiate Basketball Hall of Fame. After defeating prostate cancer in 2001, Boeheim has also waged a full-court press against the disease, raising millions of dollars for research and patient support.

"He and [University of Connecticut head coach] Jim Calhoun are both contemporaries of mine," Cingiser says. "Neither of them had won a championship in 1986. I cannot imagine that they're still going."

Cingiser, who left Brown after the 1990–91 season, is now retired in South Carolina, happy to play golf and reminisce about leading his alma mater to the only league championship in its history. For him, he says, it was never all about basketball. At the age of seventeen, he turned down a full athletic scholarship to defending ACC champion Duke to play for a Brown team that had never won an Ivy title. In 1962, he said no thanks to the Boston Celtics, who had just drafted him, and instead taught and coached at a Long Island high school. After his coaching stint at Brown, Cingiser took a job as a summer-camp director for a few years before returning to high school teaching and coaching.

So, even when it came to planning the Xs and Os in the most important game of his career, Cingiser didn't focus only on beating Syracuse. When it came time to decide game strategy, he knew the best chance the Bears had against Syracuse would be to limit the stronger team's time of possession. If Brown could just hold onto the ball and run time off the clock, perhaps they could slow down the Syracuse offense.

But the Bears hadn't played that way all year. What got them to the tournament in the first place was an up-tempo approach. Cingiser asked his players what they wanted to do. "To a man, they all said, 'Let's go play the way we play,'" he says. "And you know what? It was the right thing to do. Because if you play the other way and you get beat—which is probably going to happen anyway—you don't even have a chance to enjoy it. So that's what we did."

The Forward

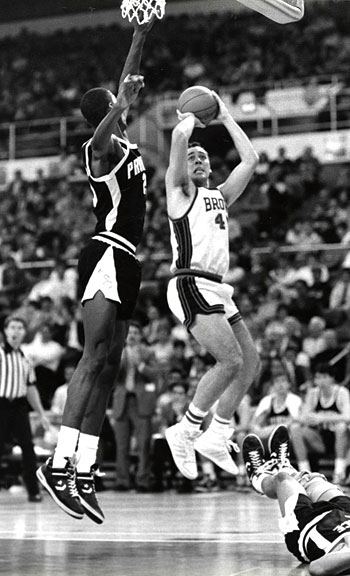

With Brown trailing, 20–19, against Syracuse midway through the first half, Patrick Lynch '87 came up to the free throw line with a chance to put the Bears on top. He dipped and shot, knocking the first one down. He hit the second one too, to put the Bears ahead. An unthinkable upset suddenly became a possibility as Brown took the lead, 21–20, over a contender for the national championship.

And then Syracuse went on a twenty-six-point run. And that was the end of that.

A junior at the time, Lynch was two seasons away from playing professionally in Belfast, Ireland, for the first of three seasons in Europe. In a three-year break between his second and third professional seasons, Lynch earned his law degree at Suffolk University.

In the NCAA tournament, Lynch faced Syracuse's Howard Triche, who was also a junior that year. Triche was just establishing himself in the starting lineup, but he already had dreams of a basketball future. "Like any other kid," he says, "I guess I had aspirations of playing in the NBA."

Triche did get his chance with the New York Knicks the following year, but he was cut before the season started. He is the only Syracuse starter in the Brown game who would not play professional basketball. Ironically, he played against Lynch, the only Brown starter who did play professionally.

After their basketball careers ended, both Triche and Lynch stayed near their alma maters. Lynch, who is originally from Pawtucket, Rhode Island, became a state prosecutor in his home state, and Triche, who is from Syracuse, New York, joined the staff at the local Budweiser plant, where he has worked ever since. These days he gets to watch his nephew, Syracuse guard Brandon Triche, star on the same court where Howard once helped defeat Brown.

Lynch, who went on to become Rhode Island's attorney general, now runs his own law firm and consulting group in downtown Providence. He started the business after leaving the attorney general's office and losing the Democratic gubernatorial primary in 2010.

Through it all, Lynch says, basketball—and the values the game taught him—helped him at each stage of his career. Even while campaigning for governor, he still kept a photograph in his office of himself shooting a free throw in a 1986 game.

"Especially at Brown than at other places," he says, "you find that there's more value in losing than there is in winning, because you learn more about yourself in that process.

"You know, you don't win them all."

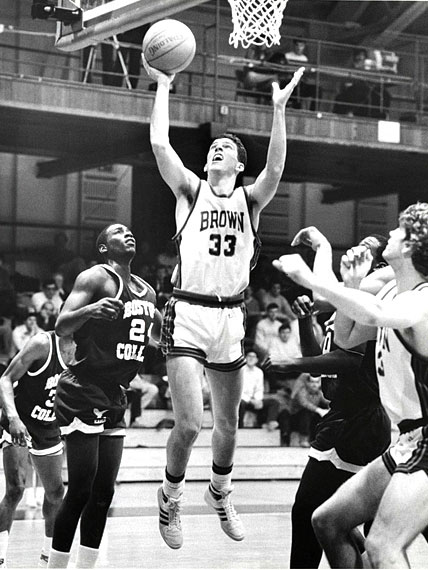

The Center

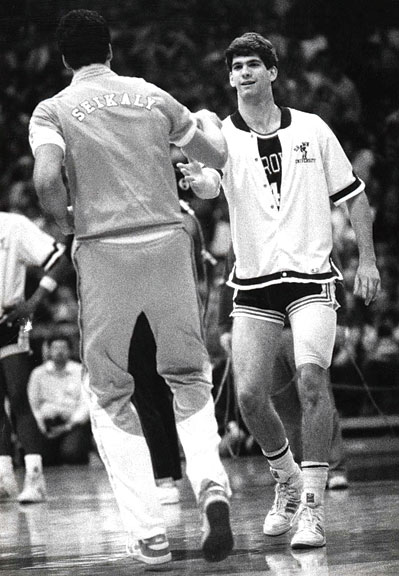

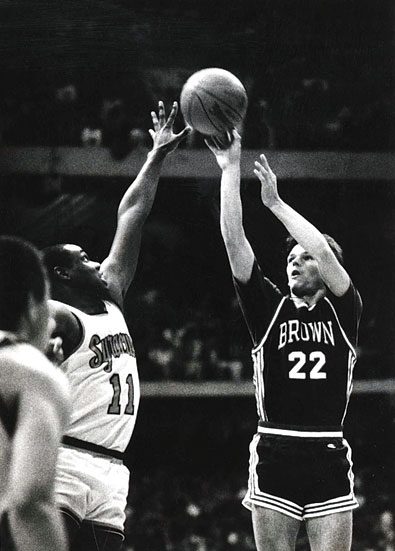

Although center Jim Turner '86 was the Ivy League Player of the Year in 1986, he was no match for Syracuse's Rony Seikaly. That year, Seikaly, a sophomore, was in the middle of a career that would end with his holding the school record in rebounds and place him second all-time in blocked shots and fourth in scoring. He was almost certainly headed for the NBA.

According to one of the TV announcers working the Syracuse-Brown game in the NCAA tournament, Turner, on the other hand, was "probably the only six-ten conference player of the year who will not care what happens on draft day."

While Seikaly went on to play for the Miami Heat, the Golden State Warriors, the Orlando Magic, and the New Jersey Nets during a ten-year pro career, Turner became an investment banker. In fact, Turner had barely dried off from the postgame shower when Dave Zucconi '55, who was then executive director of the Brown Sports Foundation, introduced him to an alumnus who happened to be a managing director at Lehman Brothers. Turner, an applied math-economics concentrator, made such an impression on the Lehman executive that he asked Turner to interview with the company. "The next week, I was [interviewing at] Lehman," Turner says. "And a few days after that, I got the job offer."

Turner is now head of debt capital markets at BNP Paribas, one of the world's largest banks. He advises Fortune 500 companies on how to access debt markets in the United States and around the world.

For his part, Seikaly has also found investment success since retiring from basketball. During his first season in the NBA, Seikaly began investing in real estate, starting with an office building in Washington, D.C. The deal went well, he hit on more investments, and, once he retired from basketball, his business grew into a multi-million-dollar company.

Even as he was averaging double-doubles in the NBA, Seikaly says he never forgot that he would eventually have to walk away from basketball. "Sometimes, when you're in the midst of it, you're not very realistic," he says. "You think you're just always going to make money, and you're always going to be able to take care of your boys and your homes and your seventeen cars. I was always a person that figured I only need one car to get me to practice."

These days, Seikaly is back to performing, this time as a DJ at clubs around the world. But no matter what he is doing, Seikaly says that basketball has always influenced him. "What basketball teaches you," he says, "is discipline. It teaches you how to focus. It teaches you to set goals for yourself and achieve them."

The Point Guard

Heading into the game, point guard Mike Waitkus '86 knew Brown would probably lose to Syracuse. But he wasn't going to let that stop him from enjoying the experience—even if he did have to defend Syracuse star Pearl Washington, the stocky but fast-as-light guard.

In the final minutes, with the game well out of hand, a small contingent of Brown fans standing behind the bench started chanting, "We're having fun, we're having fun." Waitkus turned around and smiled at the crowd.

What was Pearl Washington focused on during the tournament? "Winning," Washington says. "I think that's everybody's goal."

Well, almost everybody.

"My focus was just, 'Hey, great to be here. Great to be in the bloody NCAA tournament,'" Waitkus says. Although a senior, Waitkus wasn't thinking about jobs or schoolwork. He didn't know yet that the summer internship at AIG he had scored through a Brown basketball connection would lead him to a job at the company. He didn't yet know he'd remain there for twenty-two years and rise to be an executive vice president. Back in 1986, Waitkus had no idea that, twenty-five years after the Syracuse game, he would be living in Chicago and working at an insurance company, Allied World, as the senior vice president for the U.S. property insurance division.

Washington, on the other hand, knew where he was going. He had to decide whether to leave Syracuse a year early or stick around for his senior year, and the NCAA tournament was his final chance to prove his value to NBA scouts. Washington played well enough to leave school early and become the New Jersey Nets' thirteenth overall draft pick.

But his career was a disappointment. "I didn't have the love of the game anymore," Washington says. "When you don't have the love for the game, that means that you're not going to put out whatever effort you need to put out in order to keep your job."

Washington was cut by the Miami Heat during his third season—the final year of his contract—the day after the Heat drafted a promising young point guard, Sherman Douglas, who had been Washington's backup at Syracuse in 1986.

Washington played two more years in the Continental Basketball Association, a developmental league. In the years after his playing days, he bounced around, working in rec centers, coaching his old AAU team, and even becoming a high school girls' varsity basketball coach for a year. He returned to Syracuse to get his degree in communications in 1999. And for the past six years he has worked on the board of education for the state of New York.

And so life has turned out unpredictably for both Washington, whose future seemed certain at the time, and for Waitkus, who had little idea where he was going after graduation. "I wasn't thinking that far ahead," Waitkus recalls. "I was trying to figure out, 'Okay, I need to get a job, make a living to pay off my student loans.' Pearl was thinking, 'Okay, I'm going to be a gazillionaire, I'm going to be a superstar.'"

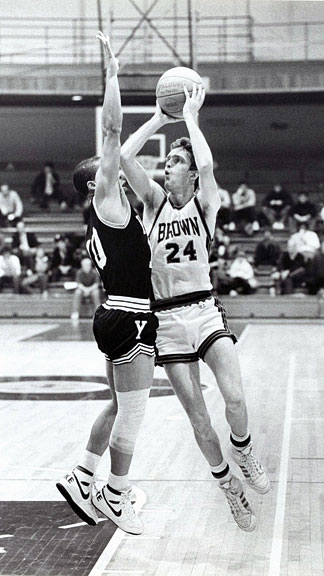

The Forward

Brown forward Todd Murray '87 was ready to handle the pressure of playing against Syracuse in the Carrier Dome. Murray, who had worked at a Syracuse basketball camp ten months earlier, had played too many pickup games against those very same Syracuse players on that very same court to be intimidated.

His ease became apparent on Brown's second possession, when Murray came off a screen at the top of the key and used what little space he had to knock down a deep jumper, putting Brown up 2–0. "I must have just gotten it over the top of Wendell Alexis's outstretched fingers," Murray recalls. "All I really remember was his armpit coming at me."

Alexis, a lean, high-flying power forward, was a cocaptain of the Syracuse team and a future Golden State Warriors draft pick. He ended up being cut before ever playing an NBA game and instead headed to Europe, where he had an eighteen-year professional basketball career. He then coached in Europe until 2008, when he finally made it to the NBA as an assistant coach for the NBA development league's Austin Toros, an affiliate of the San Antonio Spurs. Since his days at Syracuse, Alexis has never had a job outside basketball.

Murray, on the other hand, ended his basketball career when he graduated from Brown the following year. Ever since, he has been in business. He earned his MBA at Duke in 1992 and is now the president of sister companies, Great Nordic ReSound and Beltone Electronics, which manufacture and sell hearing aids.

Even now, Murray's Brown connection is strong. He is married to Kristen Simmons Murray '87, a former All-American lacrosse player at Brown. They have three children, ages ten to sixteen, and their oldest daughter, Kelsey, is considering following in her mother's footsteps and playing lacrosse at Brown in a couple of years.

Murray credits his basketball days with teaching him to deal with pressure. He says stepping up to hit a key shot when everyone is watching is not all that different from presenting to a board of directors or making a sales pitch to a potential client. "There's a huge correlation between those moments in sports and those moments in business life," he says. "And when you add them all up, they produce success."

The Shooting Guard

Different players remember different things from a championship season. Shooting guard Darren Brady '86 remembers playing number-one-ranked North Carolina, winning the Ivy League Championship game, and facing Syracuse in the NCAA tournament, of course. But the memory that has lingered longest is what he learned about the importance of team chemistry.

Brady was a naturally selfless player. Against Syracuse, he led the Bears in assists, picking apart Syracuse's zone defense to find the open man. On the other end of the court, he defended Rafael Addison, a six-foot-seven-inch guard about to be drafted by the Phoenix Suns.

"Although there's always some standout individual players, it takes a group of individuals," says Brady, who has been a chief executive at various energy companies since 1997. "And it takes the chemistry that goes along with that to have success as a team. I think chemistry is also an important part of successful companies." Brady, who is now the chief operating officer of Five Point Brothers, an Atlanta-based energy company, says the 1986 team would not have made it to the NCAA tournament without such solid team chemistry.

Since the Syracuse game, Brady and Addison went on to very different careers. Brady entered the business world, while Addison, also a senior in 1986, began an eleven-year professional basketball career that began with the Suns and went on to include stops with the Charlotte Hornets, the New Jersey Nets, and the Detroit Pistons. After retiring from the NBA, Addison began a ten-year run coaching the team he'd once led to a state championship, at Henry Snyder High School in Jersey City, New Jersey.

Although Brady entered business and Addison stuck with basketball, they ended up with jobs that were comparable in many ways. As a business leader, Brady says his job often entails a kind of coaching, as he tries to recreate the team chemistry he remembers from his time at Brown.

"Personality, leaders, style: you know, all of those things have to click," he says. "You've got to make sure that you help orchestrate that, just like a coach would help orchestrate his players."

Daniel Alexander, a history concentrator from Powell, Ohio, is a Brown Daily Herald senior editor. He also covers Providence College basketball for the Associated Press.