Few moments stand out for a writer like the first time you're told by someone that your work makes her sick. I had e-mailed a prospective agent a copy of my just-completed first novel. She e-mailed back to say it was "nauseating," and that was the end of that.

"They keep calling my book a horror novel," I told my mother. "It's not horror."

"It's about dead people," she pointed out unsurely.

"That's not horror," I said. "It's life! People die every day!"

"Not dead people who are rotting, decaying zombies," she pressed. "And you describe them in such loving detail."

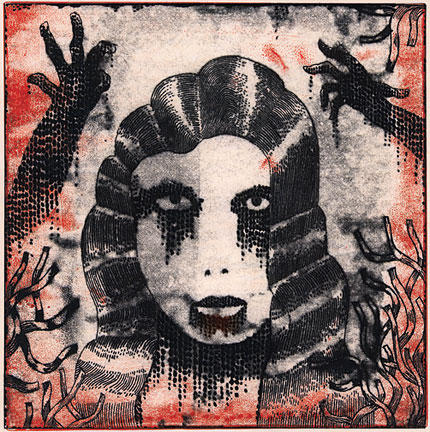

My bewilderment wasn't because I thought writing horror was beneath me. The problem was my book didn't fit my definition of horror—namely, anything I, personally, am too squeamish to read or watch. By this yardstick, the Saw franchise, Joyce Carol Oates's Haunted, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, and my vegan partner's pamphlets about the miseries of factory farming are "horror." Hellraiser, Stephen King's It, Rosemary's Baby, and my own book, by contrast, are merely a grand old time.

Where does the difference lie? Much of it is subjective, of course, bound up in emotion, memory, life experience, and instinctive feelings of attraction or disgust. And that's the beauty of it. That's why I'm glad many of my readers interpret my book, its genre, its characters, and its storyline so differently than I ever imagined when I wrote it.

In the world of book blogging, debate rages constantly about what separates "literary" from "genre" fiction, about how genres are defined, about who fits where and what's called what. But in the end, quibbling over taxonomy is useless. It's each reader's visceral reactions that ultimately settle the question. Some readers indeed found my book nauseating, others didn't. It's horror; no, it's fantasy; no, it's science fiction. It's violent; it's not at all violent. It's a commentary on consumerism, gluttony, spirituality, environmentalism, and government bureaucracy. It was as if I had written several dozen different books.

It's rather thrilling.

My collegiate self was an enthusiastic reader but a poor student of literary theory. Even so, my perspective was changed forever by the idea that a book isn't merely what the author says it is. It's a living thing, mutating constantly as others read it and interpret it, making it "their" book just as strongly as it's mine.

I wrote a horror novel, or maybe I didn't. That's a question between every new reader and the book itself, and that's what keeps stories, even stories with dead people, truly alive.

Hilary Hall '92 is the author of the novels Dust and Frail, written under the pen name Joan Frances Turner.