Midnight Rising: John Brown and the Raid That Sparked the Civil War by Tony Horwitz '80 (Henry Holt & Company).

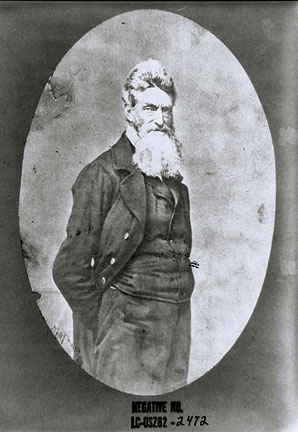

Tony Horwitz likes walking in what he calls "the footsteps of history." He marched with reenactors over Civil War battlefields on his way to writing Confederates in the Attic, his best-known work. For his next book, Blue Latitudes, he joined a crew of sailors retracing one of Captain Cook's voyages. He then followed the trail of the conquistadors for A Voyage Long and Strange. In his latest adventure, for Midnight Rising, he follows the footsteps of one of the most controversial figures in U.S. history: John Brown (no relation to Brown's early benefactor).

In October 2009, Horwitz joined other "pilgrims" to retrace the path to the federal armory that Brown and about twenty others seized 150 years earlier in a failed attempt to ignite a slave insurrection. The march brought Horwitz no closer to his quest to get "inside the heads" of Brown and his comrades, but it resulted in the best narrative yet of the origins, events, and aftermath of the 1859 raid.

History has not been kind to John Brown, who has been called a madman and a terrorist. But these labels don't fit, Horwitz argues. Harpers Ferry was no "al-Qaeda prequel," Horwitz writes; Brown was no "alienated loner in the mold of recent homegrown terrorists"; and, as for Brown's madness, "diagnosing mental illness at a distance of a century and a half is a dubious exercise."

Horwitz argues that in many ways Brown was representative of his time. Devoted to his family—he fathered twenty children, nine of whom died before reaching the age of ten—Brown instilled in his sons and daughters a deep sense of moral absolutism drawn from his Calvinist background and tinged with the rising evangelicalism of the day. He imbibed the entrepreneurial spirit of the era and suffered along with millions of other Americans when economic busts bankrupted his business ventures. Only in his violence on behalf of abolitionism did he distinguish himself. After he led a band in Kansas that butchered five proslavery men with broadswords in 1856, proslavery politicians put a price on his head, while northeastern reformers invited him into their parlors. He dined at the homes of Emerson and Thoreau.

Most of Horwitz's book is devoted to the climactic events at Harpers Ferry, and his narrative of the raid is at once gripping and heart-wrenching. His research has unearthed new gems—we get our first glimpses, for example, into the personal lives of Brown's comrades—and his prose flows as urgently as a true-crime story. The result is a provocative, if disturbing, account of the power of violence to effect change. William Lloyd Garrison was adamant that abolitionists use nonviolent methods, yet he was so moved by Brown's actions that he eulogized him in Boston. Frederick Douglass said that Brown's "zeal in the cause of my race was far greater than mine.... I could live for the slave, but he could die for him." Horwitz doesn't mention him, but Francis Wayland, who retired as Brown's president two years before the raid, praised John Brown's "coolness" and "bravery."

The respect that Wayland and others showed Brown raises crucial questions about the relative merits of compromise and extremism. Wherever you come down on these issues, Horwitz leaves no doubt that the footsteps John Brown took toward Harpers Ferry led directly to the American Civil War and the end of slavery.

Associate Professor of History Michael Vorenberg is the author of Final Freedom: The Civil War, the Abolition of Slavery, and the Thirteenth Amendment.