On a cold night last fall on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, the marbled lobby of the American Museum of Natural History had been transformed into the setting for a swanky cocktail party. More than 500 people had paid between $1,000 and $100,000 to attend. The museum's giant barosaurus skeleton was aglow in purple light, and an hors d'oeuvres buffet featured dishes from around the world served up in copper and ceramic tureens. One cocktail waitress carried a bar chime around the room, sweeping it with a stick at regular intervals to wash the crowd with a sound like falling water.

For the past thirty years, the purpose of Human Rights Watch has been, according to its website, "to hold oppressors accountable to their population, to the international community, and to their obligations under international law." Although it is based in New York City, Human Rights Watch has offices all over the world and is likely to have more soon, thanks to Soros's gift.

Unlike its more visible cousin, Amnesty International, which operates by rallying its mass membership around such actions as letter-writing campaigns, Human Rights Watch is particularly adept at using the press to expose systematic human rights abuses and at exerting direct pressure on policymakers and government officials. Its success is based on combining emotional outrage with a meticulous devotion to factual accuracy.

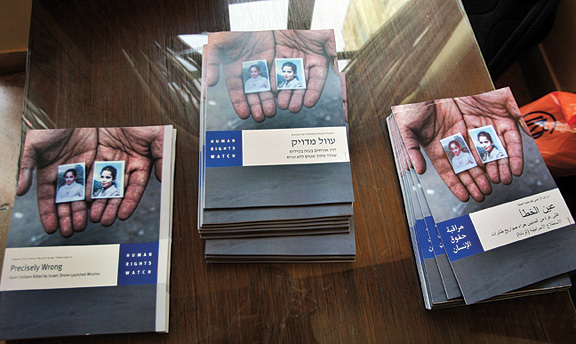

The group issues an annual "World Report" on human rights, which often generates a great deal of media attention, and follows it up with a steady stream of reports documenting specific rights abuses. In the first half of December alone, for example, Human Rights Watch issued reports on attacks on teachers and schools in Pakistan, on the year's abuses against migrant workers throughout the world, on the overuse of violence by Indian troops on the border with Bangladesh, and on the excessive time spent in New York City jails by nonfelony defendants awaiting trial. It has been called the greatest nongovernmental organization since the Red Cross. In a largely critical article last year about the group's repeated emphasis on what it sees as human-rights abuses by Israel, the New Republic conceded that Human Rights Watch "is widely considered the gold standard in human rights reporting—an organization whose conclusions nobody can afford to ignore."

For twenty-five of its thirty years, one of the people most responsible for shaping Human Rights Watch has been Kenneth Roth '77. As the group's executive director for almost eighteen years, he has both presided over and been a catalyst for the transformation of human rights work from an idealistic pastime into a legitimate profession. "Human rights has moved from being a slightly marginal idealistic way of viewing the world—well-meaning activists who didn't always achieve a huge amount—to being a much more professional enterprise," says Iain Levine, Human Rights Watch's program director. "Has Ken played a part in that? Unquestionably."

In response, the groups that would later combine to form Human Rights Watch developed an almost religious devotion to factual accuracy. Helsinki Watch began in 1978 to monitor the Soviet Union's compliance with the civil rights portions of the Helsinki Accords. The 1980s saw the founding of a number of "watch groups" around the world—America Watch, for example, monitored the various regimes in Central America—which eventually became known as "The Watch Committees." All these groups merged in 1988 to form Human Rights Watch.

By the time Roth took over from Neier as executive director in 1993, Human Rights Watch had sixty employees and a budget of $7 million. The organization has since grown to employ 300, with offices in fourteen cities around the world, staff in ninety countries, and a budget of almost $50 million. "I probably would never have been hired if I had showed up at the door today," Roth admits.

Roth has overseen the organization's "professionalization," demanding expertise and accuracy in all things. He pronounces words precisely. He can call a dizzying array of facts to mind and synthesize complex information on the spot. With long, spindly fingers, dark hair parted on the side, and plain, silver wire-rim glasses, Roth is "slightly geeky," as one of his colleagues affectionately describes him, with a "slightly geeky sense of humor. He's not warm and fuzzy. He's kind of more sharp-edged." His longtime friend Anthony Romero, the executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union, says, "He's one of the great humanists. He believes in the dignity of the human experience."

Roth recently spent the afternoon in a plush wood-paneled room at Yale Law School, which he attended after earning his AB in history at Brown. Over the course of two hour-long talks and two wide-ranging question-and-answer periods, he looked relaxed. He easily discussed topics like the military and political circumstances of the war in Eastern Congo, the election in Burma, the relative effectiveness of different types of sanctions, the European Union's internal politics, the moral implications of anti-imperialism, the Lisbon Process, the "scorched earth" approach of the Sri Lankan government in its war with the Tamil Tigers, the African National Congress's sentiment toward the International Criminal Court, India's foreign policy toward Burma and Sri Lanka, China's self-image with regards to mass atrocities, the difference between the apartheid divestment strategies of the 1980s and similarly inspired corporate divestment movements today, the UN Global Compact, and the reason the Obama administration has not yet closed the prison at the Guant√°namo Bay detention camp.

Roth also is the guiding sensibility for the "World Report," which summarizes human rights in the ninety countries and territories where the organization works. Roth's introduction synthesizes the group's work for that year around a theme. At the press conference where he releases the report, Roth usually draws from his essay to describe some of the organization's major initiatives and then takes questions.

"He could be asked about any one of ninety countries," Iain Levine says. "I've never heard of him screwing up—getting the wrong country, the wrong issue, the wrong leader. I always think, How on earth? It makes him a very authoritative figure. When you can demonstrate that level of mastery of the subject matter, people do sit up and take notice."

Each week, Human Rights Watch publishes two reports, which can sometimes run to hundreds of pages, and about a dozen shorter bulletins. This "naming and shaming" is at the heart of the organization's strategy: identifying and describing, in excruciating detail, human rights abuses around the world.

In Human Rights Watch's October 2010 report "Beaten, Blacklisted, and Behind Bars: The Vanishing Space for Freedom of Expression in Azerbaijan," for example, Afgan Mukhtarli, a photographer for an Azerbaijani newspaper, describes his beating while covering a political demonstration in that country: "That's when about twenty policemen attacked me," he is quoted as saying. "Four of them twisted my arms and made me kneel, as others kicked and beat me. They broke my right wrist and left knee. They were cursing me and my newspaper and kicking with their boots, which had iron heels."

To compile such reports, Human Rights Watch recruits researchers who speak the languages of the countries where they work. These staffers may spend years gaining the trust of local activists and human rights groups to collect sensitive information. Nothing is published without independent verification.

"Ken has a tremendous commitment to making sure that we get the facts right," says Levine. "And that we document the facts in an objective, dispassionate way. It doesn't mean you can't be passionate about human rights activism, but in the documentation of it, it had better be rigorous, methodical, objective." The reports, Roth says, are "material of the caliber that you would find in the top newspapers around the world, material that the major foreign ministries would be reading. We need to be operating at that level."

Still, Human Rights Watch is not just a publishing company, Roth is fond of saying. The group uses its research as the basis for a wide range of diplomacy and activism, in some places applying quiet pressure behind the scenes, and in others shaming by creating an "intense press spotlight," as Roth describes it: "Governments will go to great lengths to avoid a PR problem that won't go away." Staff members work with the press to frame and publicize human rights issues and to provide information to the UN and the International Criminal Court. In addition, they may help set up tribunals and negotiate the deployment of peacekeeping forces or bring pressure on governments with particular influence over the targeted country.

"It's not enough to be right," Levine explains. "You have to find a way of convincing either the perpetrators or those whose actions or inactions facilitate the human rights violations to do something different. Ken thinks very strategically about how you go from identification of the violations and the violator to bringing the pressure that will change the situation."

In many countries, human rights are narrowly defined, and so the group also tries to broaden what's considered abuse. In May 2001, Roth and his colleagues got word of the case of fifty-two Egyptian men who were arrested aboard a floating gay nightclub called the Queen Boat. The men were charged with "habitual debauchery," "obscene behaviour," and "contempt of religion," and were beaten and tortured by the Cairo police. But when Human Rights Watch called for a protest, the local human rights organizations objected.

"They said this wasn't a human rights violation, this was immoral conduct," Roth recalls. "When we probed a little further, we realized what they were most worried about is that the Egyptian government would discredit them for taking on an issue that was broadly seen as immoral, and that their bread-and-butter work would be compromised if they took on gay rights. We had to develop a strategy to try to get Egyptians to think of gays as having rights the same way everybody else does."

So Human Rights Watch published two reports in rapid succession focusing on torture in Egypt. "Egypt's Torture Epidemic," released in 2004, focused on the beating and torturing of ordinary Egyptians accused of crimes. This report, Roth says, "was deliberately issued to set the stage" for the next one, which came out less than a week later. "In a Time of Torture" documented "the government's increasing repression of men who have sex with men." Roth explains: "We presented the reports one after the other, and tried to highlight the fact that everybody is vulnerable to this. You can't allow one category of victim without risking other categories of victims. By portraying it as an issue of torture, rather than explicitly gay rights, we made progress."

Human Rights Watch is not without its critics. In particular, the group's work targeting human rights abuses by Israel has drawn criticism from those who detect an anti-Israel bias. In 2009, the group's very founder, Robert Bernstein, wrote in a New York Times editorial that the organization "has been issuing reports on the Israeli-Arab conflict that are helping those who wish to turn Israel into a pariah state." Bernstein drew a distinction between "closed" and "open" societies and argued that "at Human Rights Watch, we always recognized that open, democratic societies have faults and commit abuses. But we saw that they have the ability to correct them—through vigorous public debate, an adversarial press and many other mechanisms that encourage reform."

Last spring, the New Republic picked up the argument in an article by Ben Birnbaum that included interviews with Bernstein and other dissenting Human Rights Watch directors. In response, Kathleen Peratis, a self-described Zionist and longtime Human Rights Watch board member, wrote to the magazine: "There is no bias against Israel at Human Rights Watch, except in the minds of those who erroneously believe Israel is harmed by honest criticism. Far from harming it, I believe this work strengthens Israel."

For his part, Roth says Bernstein "was arguing that we should not report on Israel because Israel is an open society. And my two-word answer to that is: George Bush." Under the Bush administration, Roth argues, the United States "was an open society that committed serious abuses, and therefore we reported extensively on it."

When asked what first piqued his interest in human rights, Roth points to his father. To keep his four children still while cutting their hair, Walter Roth used to tell funny stories about his German childhood. At first, the stories focused on the delivery horse at the butcher shop run by Walter's father in Frankfurt. The kids called them Bobbi stories, after the name of the horse.

As the children got older, the stories got more serious. The suburban Chicago town where they lived was a world away from the life in Nazi Germany that Walter had fled a few decades before. He served on the local school board and worked as chief technical officer at an electronics corporation; his wife taught high school math. But while he cut the hair of his oldest son, Kenneth, he spoke about, "the evil that governments are capable of."

Similarly, Roth got early lessons in how to negotiate for change. Once a week the Roth parents and their children met for Family Council, where complaints were aired. "There were four children," Walter Roth recalls, "and they had an equal vote, so they could outvote us on anything." The Roths took Family Council very seriously. Any arguments during the week, no matter how small—tiffs over television shows, bedtimes, allowance—were referred to Family Council for resolution. There was a rotating chairmanship, and motions were all logged into a book and numbered.

"But then there was a discussion before [the children] voted," Walter says. "In the discussion, they learned that you have to listen to both sides." The kids all became "little politicians," too, negotiating in advance of Family Council to win votes.

Not surprisingly, when Kenneth Roth arrived at Brown he quickly became an activist. He participated in the 1975 takeover of the University Hall organized by minority groups in protest of proposed financial aid cuts. ("Blacks Beat Brown" read a headline in Time.) He volunteered with a prisoner advocacy organization and visited each week with inmates at Rhode Island's Adult Correctional Institute.

A history concentrator, Roth was fascinated by political philosophy and theory—the "morality of public policy," as he describes it. From his political science and philosophy classes he learned that "it's not enough to cite the law."

"Laws have to be principled to be effective," he says. "What really matters are public norms of behavior—the public's sense of right and wrong." Even today, says program manager Iain Levine, Roth has "a very very strong commitment to moving beyond policy prescriptions to how you tell the story," how you generate enough outrage to "mobilize political and public pressure" to get policy prescriptions implemented.

"Whether there's a law prohibiting that practice or not is less important than whether the outrage exists," Roth says. "Because we can build on the outrage to create a law."

After Brown, Roth went on to Yale Law School. He had a sense that he wanted to pursue some combination of teaching, criminal law, and international law. "There was one human rights course at Yale at the time," he recalls. "I dutifully signed up for that course each year for three years, and each year they cancelled it. So I had no training whatsoever. To make matters worse, when I graduated there were no jobs in human rights. Human Rights Watch had just started. It had two employees. Amnesty International was also tiny." So he clerked for a year, then joined a private law firm while volunteering nights and weekends for the Lawyers' Committee for Human Rights. "I was a kid" he says, "who walked in and said, 'I'd like to do something.'"

Roth had been volunteering for only a few months—he had represented one Haitian asylum seeker—when martial law was declared in Poland. "And even though I didn't speak Polish, and had never been to Poland, they said, 'You take care of it,'" Roth recalls. "So I started reporting on events in Poland and ultimately traveled there. It's almost embarrassing when I think back to how na√Øve the whole movement was."

After a stint as a prosecutor at the U.S. Attorney's office for the southern district of New York and a staffer for the Iran-Contra investigation in Washington, Roth was hired in 1987 to work at The Watch Committees. "I was actually hired because Haiti was blowing up," Roth says, "and the people who did the Latin American work didn't speak French. I did, so they hired me, even though I had no experience with Haiti other than having represented that asylum seeker. That first election I went to cover, the army decided to blow it up by shooting everybody they could find until they cancelled the election. That was my first investigation."

At the time, human rights work was stymied by the limits of communication. "The pace used to be glacial," Roth recalls. "Amnesty, in the early days, literally wrote letters to verify: 'Dear so and so, we understand your brother is in prison. Could you please verify the following?' And mail it to Guatemala. And wait two months for it to come back. Maybe."

The explosion of new technologies has transformed human rights work under Roth's watch. "Today, our aspiration is real-time response," he says. "If something happens, we want to respond that same day within the press cycle. You can only do that with modern technology." Phone calls are cheap, and satellite phones are available for researchers in remote areas without cell phone towers. Colleagues in places as far-flung as Congo and Brussels and Moscow can use video-conferencing technology. Satellite photographs help researchers verify and quantify events.

Researchers in dangerous areas have begun using smart pens; a tiny camera near the point of the pen records their handwritten notes onto a flash drive inside the pen. "So you can throw away your notes, and you can just download from the pen what you wrote and reconstruct it later," Roth says. "If you're stopped at a checkpoint, you don't have anything on you. That's a big concern in certain war zones."

Along with the rise in modern technology has come the accompanying decline in traditional media outlets, "our biggest magnifier," Roth says. Human Rights Watch has adapted by keeping up an active, easy-to-navigate website from which reports can be instantly downloaded. "At one time," Levine says, "you went, you did your report, you came back and you issued a press release and you did a bunch of meetings. Now we have so many more ways of getting the story out."

For television stations, Human Rights Watch makes video clips and interviews available. "If we don't give them the video," says Roth, "they are not going to run the story." For radio stations, the organization offers broadcast-quality podcasts. "They don't even have to do their own reporting," Roth says. "They just plug our three-minute segment onto their radio stations."

George Soros's $100 million gift is crucial to the group's newest strategy of having staff and bases in more and more places around the world. "When we started out, our first focus was on influencing United States government policy," says Roth's former boss, Aryeh Neier, who now heads the Open Society Foundations. "We wanted to leverage the power of the purse and the influence of the United States for the human rights cause. But the world has changed. The United States does not play the same dominant role internationally that it played previously."

The Soros gift will allow Human Rights Watch to almost double its annual budget, to $80 million, and to open offices in major non-Western capitals with emerging international importance. In the last year, new offices have opened in Tokyo, Johannesburg, and Beirut, and others are planned for Delhi, Nairobi, Bangkok, and Brazil. "I'm afraid the United States has lost the moral high ground under the Bush administration, but the principles that Human Rights Watch promotes have not lost their universal applicability," Soros told the New York Times. "So to be more effective, I think the organization has to be seen as more international, less an American organization."

Roth, Soros, and the thousands of donors whom the organization wined and dined this winter are betting that the new office in South Africa will be a better vantage point than Washington, D.C., or Paris from which to negotiate with Zimbabwe. They're sure that the relationships their staff creates with the Indian government from an office in Delhi will give them improved leverage in such countries as Burma and Sri Lanka.

After all, Roth says, "governments behave better when they're watched."

Beth Schwartzapfel is a BAM contributing editor.