Heart of the City: Nine Stories of Love and Serendipity on the Streets of New York by Ariel Sabar '93 (Da Capo).

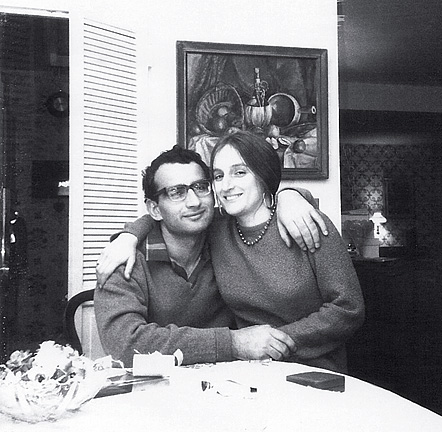

Ariel Sabar's father, Yona, was born in a mud hut in Kurdish Iraq, the son of Jewish peasants who later immigrated to Israel, where their lives were marked by struggle and hardship. Yona eventually made his way to the United States, where he married Ariel's mother, Stephanie Kruger '60, who had grown up in Greenwich Village the daughter of a CEO "and his elegant wife, the sort of people who held season tickets to the Metropolitan Opera."

Ariel told the story of how Yona and Stephanie met in Washington Square Park and were married four months later at some length in his award-winning 2008 book, My Father's Paradise, and he revisits it in his new book, Heart of the City, his account of nine couples who met and fell in love unexpectedly in some of New York City's great public spaces. The story of his parents' meeting and courtship, Sabar writes in the introduction to the new book, "showed how immigrants here could leap borders of culture and class in ways unthinkable back home. It showed how in a society as fluid as America's, any two people could fall in love, anywhere."

By why? Even in the United States there had to have been something extraordinary about the circumstances that allowed two people from such disparate socioeconomic backgrounds as Yona and Stephanie to even talk to each other, let alone let their guard down and connect emotionally.

"There's all this mythology of how love in New York works," Sabar says, citing Sex and the City, An Affair to Remember, Sleepless in Seattle, When Harry Met Sally, and most of Woody Allen's films as examples. Even King Kong, Sabar points out with a laugh, is a story of "unrequited love set at a major New York landmark."

But what about real life? "Could a vibrant public space, in some subtle but essential way, play matchmaker?" he asks in Heart of the City. Combining a journalist's devotion to research and attention to facts with a novelist's flair for setting, character, and dialogue, Sabar shows nine reasons why he believes the answer is yes. The nine different love stories he describes span five decades of New York City history. The couples meet in such landmarks as Central Park, Grand Central Station, the Empire State Building, Statue of Liberty, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Times Square, and Washington Square Park, as well as on the city's sidewalks and subway. In each case, the magic of the place itself is vital to the couple's connection.

Chesa, for example, arrived from the Philippines at midnight, disoriented and alone, with little more than a friend's address and phone number in her pocket. She had never been to the United States before. She asked a stranger how to get to Chinatown, and when she later spotted him on the A train, they struck up a conversation. Matt and Sofia, meanwhile, literally bumped into each other in midtown when she stumbled on the sidewalk and crashed into him with her viola case. Joey had run away from home and was huddled, hungry and freezing, on a bench in Central Park when a handsome sailor offered to buy her some dinner.

Bookending the stories are an introduction and an epilogue in which Sabar explores research by psychologists and others about the role of physical space in attraction and love. It turns out there are, indeed, certain characteristics of public places that facilitate engagement between strangers, and New York has them in spades. For one thing, these places draw large numbers of people, so it's inevitable that some of them will interact. "Contrary to the notion that the best-used parks and plazas are hideaways from the urban rush," Sabar writes, summarizing the research of urbanist William Whyte, "people often sought out the busiest areas of a public space to lunch, chat with colleagues, or snuggle."

Sabar says many of these places contain a common frame of reference: "a mime, a juggler, a musician, a street character. A spectacle, even a minor one, ... takes two strangers with ostensibly nothing in common and, through a shared, immediate experience, links them, even just for a moment," he writes. A third factor is adrenaline: people in an "emotionally stimulating situation" are more likely to reach out to those around them. "To me," Sabar says, "the introduction really is what grounds this in something more than light, fun, fluffy stories."

The stories are hardly fluffy. Although each couple eventually marries, Sabar is too much a realist to leave out the inevitable strife. Couples struggle, fight, lose touch. "I wanted the stories to have the texture of real life," he says. "They had these beautiful ways they met, but then it started to look like any other love affair: ups and downs, missed connections. These public places set you on the right path, but afterwards it's up to you to make it stick."