Call them strange embed-fellows. Four years ago, the ivory tower—long a haven for independent scholarship and, since at least the 1960s, a place for scholars and thinkers to regularly critique their government from a safe intellectual distance—received an unusual request from a most unlikely source. As the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan slogged on, the U.S. Army issued an invitation to anthropologists and social scientists: help us fight a kinder, gentler war. We know weaponry and kinetic ops, but we don't know culture. Help us win hearts and minds. Embed with us in country. Show us how to navigate the human terrain in the War on Terror.

These are the kinds of questions raised by the new documentary Human Terrain by Professor of International Studies James Der Derian and filmmakers David Udris '90 and Michael Udris '91. Human Terrain is both a film of ideas and a deeply personal search. It emerges largely from Der Derian's long work studying the intersection of war, culture, and media. It began, in fact, as part of a Watson Institute for International Studies initiative, its Cultural Awareness and the Military Project, which Der Derian established in 2004 with his colleagues Professor of Anthropology Catherine Lutz and Associate Professor of International Studies Keith Brown. The project, according to its website, was begun "to investigate the ethical, practical, and technological issues raised by the military's quest for greater cultural awareness."

What makes Human Terrain remarkable, however, is that it is much more than an academic exploration of abstract issues. The film's central character is Michael Bhatia '99, one of the first people brought into the Cultural Awareness and the Military Project, and the first social scientist to be killed as part of the military's new effort to join social scientists with combat units at war. Bhatia may have died in Khowst, Afghanistan, in 2008 when a roadside bomb hit his convoy, but he lives on in Human Terrain as he struggles to determine his proper role as scholar and citizen.

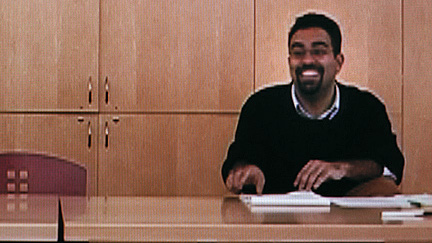

In one scene he has recently returned from a Cultural Competency in the Military conference at the U.S. Air Force's Air University. Thirty years old and dressed in an academic's button-down shirt, dark sweater, and glasses, he sits in a conference room at the Watson Institute and reads from his notes. "The center of gravity is now the perception of civilians," he says. "And so victory is defined as capturing the psycho-cultural high ground. As a consequence of this, empathy is the new key weapon of war. They're proposing a Manhattan Project of the human sciences."

No one grappled with the questions raised in Human Terrain more deeply and more personally than Michael Bhatia. Less than a decade out of college, Bhatia—a Marshall scholar and a doctoral candidate at Oxford—arrived at the Watson Institute as a visiting fellow of the Cultural Awareness and the Military Project and as a student completing his doctoral dissertation, "The Mujahideen: A Study of Combatant Motives in Afghanistan, 1978–2005." But he was equally committed to the application of his research. Already he had spent months conducting fieldwork in Afghanistan and working with the United Nations and other NGOs in such conflict zones as East Timor and Kosovo."He was working against two different codes," Der Derian explains in the film. "One, the code he had learned as a scholar, of objective distance, and then one he had learned as a concerned activist: that you need to get in and get dirty. You need to get up close to the war machine." And so it was that during his year at Watson, Der Derian says, Bhatia "became less of a researcher and more of a practitioner."

The first two sections of Human Terrain deal with the theoretical and political issues raised by the military's emphasis over the last decade of its new, "culture-centric" approach to war. The key event came in 2006, when the U.S. Army released its latest Counterinsurgency Manual. The COIN manual, as it's known, stressed nation-building and cultural competency as key tactics in guerilla warfare.

The next year, U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert Gates launched the Human Terrain System, or HTS, which embeds social scientists with military units on the ground. According to the army, HTS "was developed in response to identified gaps in commanders' and staffs' understanding of the local population and culture, and its impact on operational decisions."

The program, according to the HTS mission statement, "is the first time that social science research, analysis, and advising has been done systematically, on a large scale, and at the operational level. We advise brigades on economic development, political systems, tribal structures, etc; provide training to brigades as requested; and conduct research on topics of interest to the brigade staff."

The document insists that "HTS does not conduct lethal targeting, manage infrastructure projects, or provide schoolhouse pre-deployment cultural training." With social scientists in a country alongside combat units and troops, the military can better develop "an understanding of the societies and cultures in which we are engaged." The aim, according to the mission statement, is that "the U.S. military can reduce the need for and negative repercussions of lethal force." (A spokesperson for HTS declined to comment on the film for this story.)

The logic is clear. It's obvious that the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan will be won or lost in the hearts and minds of the citizens of those countries. But is a kinder, gentler military really a good thing? As Der Derian asks in the film: "Would this somehow pacify the military, to bring culture into it? Or ... would it somehow or other militarize peacekeeping?" In interviews with a former army interrogation instructor and other participants, Human Terrain makes clear that this goal is not always a comfortable fit.

Although West, coauthor of The March Up: Taking Baghdad with the First Marine Division, does not offer this perspective as a criticism—he is a supporter of the war and of HTS—the program has its share of opponents, many of them the very people it was designed to engage. In the summer of 2006 the American Anthropological Association (AAA) convened an ad hoc commission at the Watson Institute to study the issue of social scientists collaborating with the military. "What if we are dealing with a bureaucracy, an organization, which does harm—you know, kills?" asks one of the committee chairs in footage of the meeting that appears in Human Terrain. "There are various options. Disengage is one. Attempt to diminish the harm done by engagement is a second."

Academics are famously left-leaning, and it was something of a foregone conclusion that the AAA would issue the statement it ultimately did, in November 2007, condemning HTS as "a problematic application of anthropological expertise, most specifically on ethical grounds." As Catherine Lutz says in Human Terrain, "That is a very seductive idea, that you would be able to 'help' in a situation of crisis. What I think one has to step back and ask is, Help what? Help whom? To do what? What are the goals of the war and the occupation? Does the anthropological community want to help in that endeavor?" All of which makes perfect ideological and intellectual sense. But complicating the logic is the image of Michael Bhatia sitting at the AAA meeting, chin in hand, surrounded by a room full of his skeptical colleagues. He seems to be trying to find a third way, a way to participate in HTS without corrupting his academic beliefs. "People are adopting anthropology's methods for studying the other without adopting either their ethics or their perspectives," he observes. "If you are involved, to what extent can you dictate a freedom or an ability not to provide information?"

What is not yet clear in the film is that Bhatia was wrestling with these questions not out of academic curiosity but out of a personal sense of mission. As it turns out, he had already been approached by HTS. He was also waiting to find out whether his fellowship at the Watson Institute would be renewed for the next year. (It wasn't, mostly because the institute was undergoing a change in administrative leadership at the time.) Bhatia was in the process of trying to resolve a lifelong tension between his love for dispassionate analysis and his yearning to get out and put his ideas into practice.

"If you are engaged with military actors on the ground," he wonders aloud in Human Terrain, "and that space between reducing otherness and potentially being involved in targeting starts to get blurred—when can you say, 'I'm not simply going to provide that information to you?' Whether that's a space that can actually be negotiated?" He pauses, looks down at his notes for a moment. "Or is that just naïve?" He leans back in his chair, laughs a big nervous laugh, his mouthful of white teeth set off by his dark goatee.

It's early June. Der Derian, a man with a slender build, mussed grey hair, and blue eyes, huddles around a computer with the Udris brothers in his Watson Institute office. They are watching oil gush from the Deep Water Horizon into the Gulf of Mexico. They have lots to do to prepare for upcoming screenings of Human Terrain in Oxford and London, but they are glued to the screen, horrified. They can't tear their eyes from the carnage.

"Media is no longer simply the medium," Der Derian says later, reflecting on web cams aimed at disasters far and near. "It's no longer the conveyor of information. It's also the producer, the catalyst. What takes a local event and turns it into a global incident? It's when you have cameras on."

Der Derian cites videos of beheadings posted to the Internet and Bin Laden's recorded messages disseminated by Al Jazeera. Even the genocide in Rwanda, he says, was made possible by hate propaganda broadcast over the radio. "The military has a term for this: force multiplier," he says. In a case like the Rwandan genocide, he asks, "Would it exist? Would this event even exist without media?"

As a scholar of international relations, he analyzes questions like these in his 2001 book, Virtuous War: Mapping the Military-Industrial-Media-Entertainment Network. (A second edition was published in paperback last year.) In the book Der Derian argues that "made-for-TV wars and Hollywood war movies blur, military war games and computer video games blend," the result of which is the seamless merger of "the production, representation, and execution of war."

Der Derian, however, has not been happy simply to criticize the media. He has tried to present his ideas in his own films. His goal, he says, is "to link together the study of global media with its production." As he puts it: "You can't be one without the other. You can't have theory without practice."

While a professor at UMass Amherst before arriving at Brown, Der Derian taught a course on pressing global issues. His students learned rudimentary production techniques, and presented course sessions on the local public-access television station. "It was Wayne's World meets Bill Moyers," Der Derian says, laughing at his early efforts.

Then, in 1994, Der Derian published a piece in Wired that ultimately became the first chapter of Virtuous War. In it Der Derian detailed a new tech-savvy military for the new century. "If the old nuclear deterrent was to depend on the frightful force of mass destruction," he wrote, "the new digital strategy is to win the total information war."

The essay caught the attention of political science professor Tom Biersteker, who was then director of the Watson Institute. Bierstecker offered Der Derian seed money to start a project integrating international relations with information technology. Der Derian gave up his tenured job at UMass to become a Watson research professor. He soon secured additional funding from the MacArthur and Ford Foundations, and founded what is now the Global Media Project. It produces documentaries, hosts workshops and conferences, serves as home to Christopher Lydon's Open Source Radio, and offers a global media seminar, the capstone of which each semester is a student-produced short film.

Der Derian met David and Michael Udris shortly after they'd founded a film production company in Providence. Although as undergraduates David had studied art semiotics and Michael comparative literature, both had been involved in the visual art department. Then, as the Modern Culture and Media department was expanding, professor of visual art Roger Mayer told them about a new job showing MCM students how to use and maintain the department's cameras and editing equipment. After convincing Brown's human resources department to let them split this single full-time job, the brothers realized they didn't know how to use the equipment either.

"So we just started taking it home," Michael recalls. "And then in the course of that self-teaching, we shot a lot of film and video, and over the years just started making projects which were shown in New York and elsewhere."

The brothers have the same brown-green eyes and easy rapport of family, but otherwise they are a study in contrasts: Michael, who is tall and solidly built, has a tidy, short haircut and is clean shaven. David is lankier, his hair is longer, his face is unshaven, and his loose-fitting linen shirt is wrinkled. Their first collaboration with Der Derian was Virtual Y2K, which documented a Watson-sponsored conference on the computer-related panic around the new millennium. "I immediately decided we weren't going to do something conventional—have a one-off conference and do a book," Der Derian says.

Next they made a documentary from a series of conferences and art installations that Watson hosted in the aftermath of 9/11. The forty-five minute film, After 9/11, is an unsettling montage of images and talking heads, of news footage and lecture excerpts about the role of media and the United States' perception of itself as it prepared for and launched the invasion of Iraq.

When Der Derian started the Cultural Awareness and the Military Project, he and the Udrises began making a film about the new role of culture in modern warfare. By the time Michael Bhatia was killed, they had already made two visits to a faux Iraqi village in the Mojave Desert and filmed war games, role playing, and casualty drills. (Michael Udris, his camera mistaken for a Rocket-Propelled Grenade during a war game, got shot with a paintball in the only place on his body not swathed in Kevlar: his ear. "It bled like a stuck pig," Der Derian says now with a laugh.)

As a visiting fellow at the Cultural Awareness and the Military Project during the 2006–07 academic year, Bhatia watched footage and offered criticism on early rough cuts of Human Terrain. He suggested people to interview and places to visit. He attended conferences and collected journal articles for Der Derian. It was on an assignment from Der Derian that he'd attended the Air University conference at which he gathered the notes he reads in the film. It was probably there that he first met the directors of HTS.

Der Derian and the Udris brothers had spent three years working on and off on Human Terrain. During that time Der Derian balanced his work on the film with his other teaching and research. The Udris brothers, meanwhile, produced their own films and taught in the MCM department. Then, one day, Der Derian sent the Udris brothers an e-mail: "I just learned from his family that Michael Bhatia was killed in Afghanistan yesterday. No details yet. The war just got very personal."

The filmmakers didn't immediately know how Bhatia's death should affect the direction of Human Terrain. They dug up footage of the AAA conference, which Der Derian had shot routinely during Bhatia's year at Watson. He and the Udris brothers visited Bhatia's mother and discovered an MP3 player full of audio files recorded in the field. They found photos of Bhatia in Afghanistan and uncovered his journals and field notes.

"You're torn," David Udris says. "Should we do this? Is it appropriate to do this? Given the Iraqi and Afghani lives lost, the thousands of other service men and women, the tens of thousands wounded—does this Ivy League dude just become some case for exceptionalism? Because he has this academic background, he's therefore more important than other people?" Ultimately, however, Michael Udris recalls, Bhatia "as an individual came to embody the debate, in a way. His back and forth about the issue—am I an academic, a soldier?"

And so it's in the later sections of Human Terrain that Bhatia emerges as the vivid example of the complexities and tensions inherent in the debate. The viewer reads e-mails Bhatia wrote to his colleagues as he tried to work out the implications of his decision to join HTS and go to Afghanistan. "While the program has proven to be controversial," he wrote, "I am optimistic that given the right participants, the program has a real chance of reducing both the Afghan and American lives lost. Contrary to some of the criticism, I am not involved in covert research or activities, or in lethal targeting or interrogation." The film includes the audio of Bhatia assisting an army unit as it distributes de-worming pills to sheep farmers. He asks an Afghani man if he is part of dushman—the enemy—the Taliban. Yes, the man answers. He is. After Bhatia is killed, Human Terrain shows his mother, sister, and HTS colleagues trying to make sense of his life and death.

In the film, Bhatia's longtime mentor and friend, Jarat Chopra, becomes almost a stand-in for him. Both men come from multicultural families. They worked together as peacekeepers for the UN in East Timor. Both were Watson Institute scholars. (Chopra wrote a remembrance of Bhatia for the BAM shortly after his death.) In Human Terrain, Chopra weighs Michael's "sense of romantic history," the "profound tensions in this case between Bhatia the person and what he stood for ... and the packaging in which he found himself" as a contractor for the U.S. military.

To this day, Chopra doesn't understand why Bhatia went to Afghanistan. As Chopra says in the film, Bhatia was "trying to do good"; he is sure of that. "How he reconciled that with being part of a forward unit, with all the things that go along with being part of a forward unit," Chopra says. "I don't know."

On May 13, 2008, the U.S. Secretary of the Army awarded Bhatia the Secretary of Defense Medal for the Defense of Freedom, an award established after 9/11 "on behalf of a grateful nation" to recognize "heroism and selfless service beyond the call of duty." In the end, Bhatia's motives remain something of a mystery, and it's that lack of certainty, of clear answers to the issues of war and collaboration that gives Human Terrain its power. Why did Bhatia go? Should he have gone?

"My take-away from it all," Der Derian says, trying to decipher the meaning of his own film, "is that we all bear partial responsibility for others in our immediate life. And I had brought Michael into my immediate life. So I feel a partial responsibility."

It was Der Derian who invited Bhatia to Brown, who dispatched him to the conference that may have ultimately sent him down the road that led to HTS and Afghanistan. "But I don't like it being reduced to one cause," Der Derian says. "That's the one thing we didn't want to do in that film.

"Michael was a complicated guy."

Beth Schwartzapfel is a contributing editor.