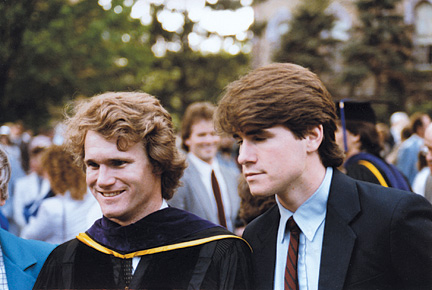

At first glance, the only things the brothers Patrick and Brian Moynihan appear to have in common are a Brown education and Irish Catholic, middle-class, Midwestern parents. Patrick is a Catholic missionary and director of the Louverture Cleary School, a coed Catholic boarding school outside Port-au-Prince, Haiti. Intense, garrulous, and outspoken, Patrick is not hesitant about seeing the hand of God at work in his life. "I'm a catalyst for conversion," he says. "I'm not the person to invite to dinner if you want everything to stay the same."

What unites the Moynihan brothers is the Haitian Project, which began in the early 1980s from an idea developed at St. Joseph's Parish in Providence. A group of parishioners wanted to provide some kind of aid to Haiti, and eventually the notion of addressing the country's lack of quality free education came up. The Louverture Cleary School was founded to provide a secondary education to some of the poorest but most highly motivated children in Haiti, on the condition that the children find ways to give back, to help improve their country.

The Moynihans have chosen to help the Haitian Project in contrasting ways, and the choices they have made in their lives illuminate two very different approaches to success. Like so many Brown graduates, they have given careful thought to how they most effectively make a difference in the world. Brian makes a lot of money and targets a significant amount—more than $150,000 last year alone—to keeping the Haitian Project solvent. As a missionary and a church deacon, Patrick makes comparatively little money. He likes to say he earns in a year what Brian earns in a day, and he's done the math to prove it. He believes this is the way it should be: Brian reaps "the rewards of a meritocracy. I personally decline those, when offered." Instead, Patrick believes that to change the world, you have to roll up your shirtsleeves and become directly and fully involved in your passion.

Patrick says that he and his wife, Christina, used to joke that, as bad as things were in Haiti, at least it had never in living memory experienced an earthquake. There had been consecutive coups d'état and the long, miserable years when François "Papa Doc" Duvalier and his son, Jean-Claude "Baby Doc," ruled like despots, wasting the nation's infrastructure for generations while they grew ever more rich.

"Because the politics were terrible," Patrick explains, "to make ourselves feel better, we'd say, 'Thank God we didn't have an earthquake.' You could see the houses, the way they're built on the hills. You just knew if we had an earthquake, it would be a bad thing. A scary thing."

In the book of Matthew, Jesus sends his twelve disciples among the "lost sheep of Israel" to drive out evil spirits and heal the sick. Among Jesus's instructions is: "What you receive for free, you must give for free." The Louverture Cleary School has adopted this phrase as its charism, or spiritual mission. For room, board, and an education, students' families pay about thirty-eight U.S. dollars a year. This covers about 2 percent of the cost of each student's education, Patrick says, "but it is somewhat significant to the parents." In exchange, students are asked to give back to their school and their country.

This is precisely what happened in the days after the 7.0 earthquake struck, less than ten miles from Port-au-Prince, on January 12. Patrick was at home with his family in Salem, South Carolina, for Christmas break. But within the first forty-five minutes, before the cell-phone network shut down, he got a call from the chairman of the Haitian Project's board, a Haitian businessman named Patrick Brun.

"I knew this was serious when Patrick Brun said, 'I don't know how I'm keeping it together,'" Moynihan recalls. "Patrick Brun had been through failures of government, he'd been shot at—he'd been through it all. For him to tell me that—I knew on a scale of one to ten, we were sitting at nine."

Before they knew most of their buildings had been spared and were safe to reoccupy, the students and staff slept side-by-side in tents on the school's athletic field. By day they fanned out to clinics and camps, and translated from English and Spanish to Creole so doctors and aid workers could help the injured and lost. The students and staff helped shovel rubble and clean up the surrounding area.

"We had students standing eight hours in a surgical room, translating for one surgery after another," he says. "That takes some real courage."

The school employs no custodial crew: the students and staff, from the smallest child right up to Moynihan himself, scrub toilets and mop and scour with their own hands. In addition to projects around the school, the students also contribute to the surrounding neighborhood. Often they teach literacy classes and help beautify the area. They assist Patrick's wife, Christina, with an early childhood development program that she runs for neighborhood children.

It was not always this way for Patrick. After Brown, he taught math at a Catholic high school in Connecticut for three years, then began working as a commodities trader at Louis-Dreyfus, in Memphis, Tennessee. He had a wife, two young children, a house in the suburbs, and a six-figure salary. But as the trappings of his financial success began to accumulate, Patrick began to care less and less, he says. He thought about his oldest brother, Michael '79, a PhD in biology from Harvard. Michael was working to genetically engineer tobacco plants—one of the very commodities Patrick was trading—but was struggling financially. Patrick's sister was having problems at her job. "Same family, same education," Patrick says he remembers thinking. "Both of those people are more intelligent than I am. Why are things going so easy for me?"

Brian Moynihan's office is perched high above the city of Boston. The floor-to-ceiling windows in his waiting room in the Bank of America building look out over the little cobblestone streets twisting below and to the Charles River just beyond, where people rowing kayaks and sculls trail little Vs of white foam behind them. The buildings of MIT are perched on the far shore, and low hills ring the city to the west.

Brian graduated from Brown in 1981. He earned a law degree at Notre Dame in 1984 and took a position at the Providence law firm Edwards and Angell. He eventually became that firm's youngest-ever partner. One of his clients was FleetBoston, and after nine years at Edwards and Angell, the bank invited him to become its deputy general counsel. Brian wore many hats at Fleet over the years, working in the commercial lending unit and on corporate strategy. When Bank of America acquired Fleet in 2004, then-CEO Ken Lewis tapped him to become president of wealth management. Since then, Brian has also served as president of corporate and investment banking, president of consumer and small-business and credit card banking, and general counsel.

Moynihan was something of an underdog candidate for the CEO position. When Ken Lewis retired unexpectedly at the end of last year, he did so after the bank's controversial acquisition of Merrill Lynch. Stockholders had accused Lewis of covering up big holes in Merrill's books, and of overpaying by so much that the bank had been forced to ask for a second government bailout. Reports at the time said the board was looking for an outsider to lead the bank through such challenges as sagging morale, a new thicket of government regulations, and subprime-mortgage losses. Only after several of those choices fell through did the board tap Brian Moynihan, "one of the bank's longtime soldiers [who] stood by ready and willing to take a job that others had turned down," as the New York Times opined at the time.

Brian and Patrick grew up with a six-year gap between them, the two youngest boys in a family of nine. Their father was a research chemist with DuPont in Marietta, Ohio, and though he made a decent living, he never knew how much money he made, Patrick quips, until he stopped paying all that college tuition. "They were spread thin," Brian says."They took all their resources, both financial and energy, and threw them on the table, so to speak, and said, 'We're all in.'"

Brian remembers the four oldest brothers passing down a single set of Christmas sweaters, which gradually made their way through the boys."I had the smallest one," he says, "and then I grew into the next and the next and the next. I had to wear them all." The houseful of siblings meant there was always someone around to play soccer, basketball, chess, or Ping-Pong. The competition could get fierce. "You had a lot of people who were smart and knew what they were doing," Brian says, "and didn't mind winning."

Brian carried that competitive spirit with him onto the rugby field at Brown. His coach, Jay Fluck '65, remembers him as "clever, smart, and quick. He would not have impressed you as being a wonderful physical specimen. But he understood the game very well, the tactical position where decisions were made. His decision-making skills were quite good. "Brian was "a middle-Ohio kind of guy," Fluck says. "He did not come from some slick New England prep school. His hair was always disheveled, his shirt hanging out. But he was extremely well-liked and had a tremendous amount of leadership capacity."

Fluck recalls a trip the team took to the National Sports Center in Cardiff, Wales. Patrick was still an undergraduate, and Brian, now a successful alumnus, also was on the trip. "Brian and I were at the back of the line talking to our host, a major coach in Wales and director of the National Sports Center," Fluck says. "Patrick came up to us with his tray and said, 'My God, if this is all we're going to get to eat, I'm going to starve to death!' Brian just said, 'Patrick, go sit down.'" Fluck chuckles. "Tact wasn't his major trait."

In the late 1980s, while he was still at Edwards and Angell, Brian was approached by fellow St. Joseph's parishioner Charlie Wharton about getting involved in a new, small nonprofit that Wharton had established in collaboration with the church. At the time, the Haitian Project consisted of an orphanage and a school, and both were directionless and in disrepair. The orphanage was eventually phased out, but the foundation of today's Louverture Cleary School had already been established: a boarding school for gifted but impoverished students that kept kids on campus during the week and sent them home on the weekends.

In a country where the few students lucky enough to get an education often find little in the way of opportunities to make them stay, Wharton and his fellow board members (including Peter Cerilli '78) saw the importance of keeping the kids "grounded in their culture and their background and their family," Wharton said. "And yet, while on campus during the week, they were safe, they were fed, they were educated."

Brian took a special interest in the project and eventually became chairman of the board. He also helped run the school's day-to-day operations. "This was not your usual board—not a go-to-the-meeting-and-go-home type of thing," he recalls. "I can remember talking to the students on a speakerphone in Providence. They're all upset. 'The world's going to come to an end, this teacher, she's too tough, and she makes us work too hard.' They're speaking Creole; somebody's trying to interpret it for us. And Charlie and I and Peter Cerilli are sitting there trying to negotiate this from a conference room in Peter's law firm."

In 1991, after the ouster of Haiti's first democratically elected president, Jean-Bertrand Aristide, triggered a U.S. embargo that increased the cost of running the school by a factor of two or three, Wharton and Brian stepped in and personally guaranteed a $10,000 line of credit to keep the school afloat.

"I think we all have a duty to give back," Brian says.

Patrick, meanwhile, was reaching the same conclusion. Back then, he recalls, Michael Jordan was all over the news. When Jordan signed a contract for what was then a record-breaking $30 million dollars, Patrick compared it to the pay he'd received as a high school teacher, and knew something was wrong. "Why did God make this world this way?" Patrick says he asked himself. "Finally I realized—this was a literal revelation; it came to me after reading the gospels of St. Francis—that God didn't. We decide that a basketball player would make a lot of money and a math teacher wouldn't. God gives the talents; we set the pay scale." Patrick concluded, "I've benefited from this system. I should give back."

He and Christina decided to forgo all the wealth and comfort that capitalism had afforded them. Patrick began studying to become a deacon—he earned a Master of Divinity degree at Providence College in 2001—and the family arranged to carry out missionary work in Uganda. Having studied classics at Brown, Patrick was planning to teach Greek and Latin at a Uganda seminary.

There was only one problem. As Patrick puts it, his mother "slipped a gear" when she heard about the plan. She asked Brian to talk some sense into his younger brother. Brian remembers telling Patrick that he could do more good by continuing to earn enough money to be in a position to help out by providing what all nonprofits need most: money. "My view to him," Brian says, "was that if he went off and traded and made a lot ofmoney, he could give a lot of money and support ten projects instead of one."

But Patrick's mind was made up. "I said to him, 'You earn the money, and you give it. Somebody has to be there to do what is right with the money.'"

Seeing that his brother couldn't be dissuaded, Brian redirected him. He knew first hand how much Louverture Cleary was struggling. He knew he was going to be stepping down as chairman of the Haitian Project when he moved to Boston to work for Fleet. He knew how much difference a charismatic leader and fund-raiser could make for the school.

Finally, Brian told him, "Look, if this is really what you're doing, I know you're going to ask me to support whatever you do. Why don't you go look at this thing in Haiti?"

As Patrick recalls, it wasn't long after he'd taken over the school that he realized he had found his mission. The realization took an unlikely form: spaghetti, which students at Louverture Cleary love to eat for breakfast. "It's like Corn Flakes for us," Patrick says—comfort food, a way of filling the belly to start the day. In 1996, the school was having a tough year financially, so Patrick had decided to cut spaghetti from the school's budget. The students would instead rely on the free bulgur wheat Catholic Relief Services provided. The cooks warned him that the students would object.

"So I get the kids all together," Patrick says, "and I say, 'Look, if you complain to a cook, we're going to feed the neighborhood.'" This line, which his mother had used with him and his seven siblings—don't complain about your food, there are starving people in this world—is not an abstraction in Haiti.

Maybe Brian and Patrick Moynihan aren't so different after all. Both believe in the power of institutions, whether banks or churches, to trigger change, and both have used their gifts to bolsterinstitutions that do good works. Each brother is deeply proud of the other. They are joined by blood, devotion to family, and the Haitian Project. How each has helped that organization is a lesson in the divergent paths to success.

Brian says that to see him as successful because he is the CEO of the country's largest bank is to miss the point. "In my mind," he says, "success is doing something you have a passion for, doing it well, and then having fun while you're doing it. Life's too short not to have fun." When he and his law school classmates were struggling with choosing the "right" career path—whether to be a corporate lawyer or a public defender, say—a favorite law school professor once told the class not to get too hung up about what they did.

"You're only going to affect so many people—the people that work closely with you and around you," Brian says he learned from this professor. "I have ten or twelve people who work for me, so day-to-day I don't touch that many people in the organization." He says he's carried his professor's lesson with him ever since, and he passes the advice along to his children. "Don't define success as somehow you're going to change the world."

This is too modest an approach for Patrick. "Being a Catholic," he says, "means you believe that one person can make a difference." He cites the examples of Jesus and the Pope. "The courage of one can turn out to be the action of millions." In a way, both men are right. For all of his charisma and his tireless, dogged devotion to Louverture Cleary, to Haiti, and to God, Patrick has only directly changed fewer than 300 lives—the students who have graduated from the school under his watch. But how many additional lives have those 300 improved by committing themselves to work in Haiti?

Similarly, Brian knows that the decisions he makes from his perch in Boston have far-reaching implications around the world. He also knows that his ten or twelve direct subordinates will, in turn, touch their subordinates, and on and on. In fact, he says that the key to good leadership is imagining how the very last person in the chain—the teller behind the window in a neighborhood branch, say—will implement your policies.

One recent afternoon in Merrill Lynch's downtown Providence offices, Charlie Wharton, the founder of the Haitian Project and a financial adviser at the firm, introduced Patrick to a group of colleagues who'd donated to the Haitian Project in the wake of the earthquake. They sit rapt as Patrick shifts seamlessly among telling heartwarming student success stories, schmoozing about the price of Bank of America stock, and rattling off a list of equipment and expertise that the school and its surrounding neighborhood still need.

He tells them about Christina's early-childhood development program, characterizing it as a derivative of Louverture Cleary. "We have very positive derivatives," he says with a wink. "We never got in trouble about our derivatives."

Beth Schwartzapfel is a contributing writer.