The Defenders

In late 2006, attorney Zachary Katznelson '95 flew to the Guantánamo Bay detention camp in Cuba to meet with his new client, Mohammed el Gharani. Like the other several hundred foreigners the U.S. military was holding at the camp, which is at the Guantánamo Bay Naval Base, Gharani was accused of trying to kill U.S. troops in Afghanistan. Also like them, he had been declared an "unlawful enemy combatant" by the Bush administration, meaning he had no rights under the U.S. Constitution. Unlawful enemy combatants, for example, could not see the evidence against them. They were unable to challenge their detention in civilian courts. But Gharani was different from his fellow inmates in one major respect—he'd been brought to the prison in early 2002 at the age of 15. He was now one of the youngest of the Guantánamo detainees.

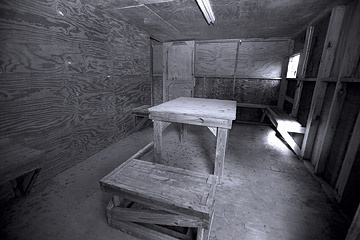

The meeting took place inside a small, windowless plywood hut that also served as an interrogation room. As was common practice, one of Gharani's feet was shackled to a metal grommet bolted into the floor. Guards had brought him to the hut several hours before his appointment with Katznelson and had left him to wait alone. But to Gharani this was at least a change in routine, a break from the twenty-two hours he was confined alone in his cell each day since he'd first been detained five years earlier.

When he entered the room, Katznelson saw a large bruise on Gharani's face. He had been quiet and depressed since Katznelson had met him a few months earlier, but he now told Katznelson that the bruise was a result of his attempt to commit suicide. He'd run headfirst into his cell wall. This was by no means an effective method of killing himself, but Gharani had become convinced that he would never leave Guantánamo, and he was desperate to put an end to his loneliness and suffering.

Katznelson, who heads the legal affairs division at the London-based human-rights group Reprieve, had grown to like Gharani. The boy claimed he was innocent—he said he'd been studying religion in Pakistan, not fighting the U.S. military—and Katznelson had come to believe him. The two developed a rapport. They chatted about World Cup soccer and about Gharani's family back in his native country of Chad. To Katznelson's surprise, they had achieved a kind of mutual empathy over religion. Although Katznelson was a Jew and Gharani a devout Muslim, Katznelson says that Gharani, "respected someone who has faith and believes in God. To him, they were both Abrahamic religions."

With Gharani cut off from the outside world since his arrival in Cuba, it fell to Katznelson to guide and mentor him. Katznelson tried to offer Gharani whatever comfort he could. "It's one of the most challenging things to do," Katznelson says. "You want to give someone hope, but if you give too much hope, it makes things worse." He emphasized to Gharani how much the boy's family wanted to see him come back to them. He told him not to lose faith. These efforts helped comfort Gharani for a time, but there would be two more suicide attempts to come.

Katznelson is one of the several Brown alumni who have volunteered to work on behalf of Guantánamo detainees. Among the others are Terry Walsh '65, Neil McGaraghan '91, David Cynamon '70, Sarah Havens '99, and Rick Murphy '70, who are all lawyers based at different firms around the United States. Together they have been on the front lines, battling both the Bush and Obama administrations for their clients' release.

These alumni have immersed themselves in one of the most important legal battles in U.S. history. They are challenging the federal government's claim that Guantánamo's prisoners should not be protected under the usual laws safeguarding basic human rights in both the United States and the world: the U.S. Constitution and the Geneva Conventions. "I think it's an understatement to say that this was one of the biggest cases I've ever been involved in," says the Boston-based McGaraghan.

At Brown, Katznelson concentrated both in history and in public policy and American institutions. He arned a law degree from New York University, then moved to the San Francisco Bay Area to work for two nonprofit organizations, the Prison Law Office (a prisoner-rights group) and the California Habeas Project (which defends domestic-violence victims imprisoned for crimes they commit against their abusers). In August 2005, he moved to London, where he signed up as a volunteer for Reprieve. Within six months, Reprieve had hired him, and two years later he was made head of the division that has since represented more than seventy prisoners held at the Guantánamo Bay detention camp, where the U.S. government still holds more than 200 alleged enemy combatants.

When they first met in the summer of 2006, Katznelson gave his new client his pitch: it was his goal, he told Gharani, "to humanize people at Guantánamo in the eyes of the outside world. They were being demonized, and that wasn't the reality." As the pair worked together, the detainee began opening up to the lawyer. Katznelson discovered that Gharani had a well-developed sense of humor and liked to crack jokes. The guards had nicknamed him Chris Tucker, after the comedian.

Katznelson says he also wanted to show the world "how these cases were so much more about politics than about the law, and to educate people about the truth about Guantánamo." Gharani claimed to have been tortured there. He described beatings by guards who also subjected him to racial slurs. He said he was put though the "frequent-flyer program," a sleep deprivation technique in which a detainee was moved to a different cell every few hours for several days.

Katznelson suspected Gharani was telling the truth, but he had no way of verifying it. Then, in 2008, the U.S. Department of Justice released a report confirming that Gharani had been subject to sleep deprivation. It also said he'd been "short-chained" for three to four hours in his cell, which involved shackling him to the floor with a chain only long enough for him to stand uncomfortably hunched over. Gharani was not released for a bathroom break and, according to the report, was left to urinate on himself.

Shortly after meeting Gharani, Katznelson flew to Chad to meet with his family. Gharani's relatives had had no contact with him, and he had heard nothing from them. Katznelson became a go-between. Gharani's family lived in the capital, N'Djamena. "Every night more and more family members would come in from the countryside just to meet us and pass their love on to Mohammed," says Katznelson. "They wanted to hear the news."

On the last day of Katznelson's weeklong trip, the family threw a party at a hotel outside the city. Blankets were laid out along the banks of a river and the men—women weren't invited—ate a meal of lamb, fish, rice, and vegetables. The guests, all relatives of Gharani, ranged from poor farmers to tribal chiefs and a university professor. Katznelson made sure to take a lot of photos, and when he showed them to Gharani at Guantánamo, the bond between them deepened.

David Cynamon '70 is a tall, thin man with a fringe of graying hair. An international-relations concentrator at Brown, he earned his law degree from Harvard in 1973, then began practicing corporate law. He also did a great deal of pro bono work on the side, representing veterans who said the military had exposed them to toxic levels of radiation, for example, and African American workers who claimed that the chain store Circuit City had discriminated against them. Then he started taking on Guantánamo cases.

In person, Cynamon is affable and easygoing, but his Guantánamo cases brought out the fighter in him. He once tried to give a client there a picture of his four-year-old nephew back in Kuwait. The military insisted he first hand it over to them for inspection, but three months later officials still had not given it to his client. "I basically told them this is beyond outrageous," Cynamon says. "This picture should take someone ten seconds to review." The military was not moved. Then Cynamon threatened to haul everyone into court and get a judge to order the photograph delivered. His client soon received the photo.

All Cynamon's Guantánamo clients were Kuwaiti. He got involved with them in 2006, when a Kuwaiti lawyer who was a friend of a friend asked if Cynamon would be willing to meet with the relatives of some Guantánamo prisoners. When Cynamon met with them, they asked if he would represent their loved ones. Cynamon agreed. He says he wanted to work on "cutting-edge constitutional litigation."

In the spring of 2007, Cynamon, who lives in Maryland, sent out an e-mail to colleagues at his D.C. law firm, Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman, informing them about an in-house talk on Guantánamo he was scheduled to give. It was to be a basic update, Cynamon recalls, aimed at filling everyone in on the progress of his work and offering thumbnail sketches of a few of his clients. The other lawyers at the firm were keenly interested. A colleague e-mailed him, saying she was very much looking forward to his presentation because she had a brother who was prosecuting inmates in Guantánamo. Cynamon instantly e-mailed back, "My God, do you think he'd be willing to talk to me?" She said she'd ask him.

Her brother turned out to be Lieutenant Colonel Stephen Abraham, one of the lawyers prosecuting Guantánamo's inmates before the military tribunals set up to hear their cases. Cynamon asked Abraham to come forward and reveal what he knew about the detention center's trial system. Abraham was initially reluctant. But over several phone calls Cynamon persuaded Abraham to speak out. It wasn't all that difficult. Abraham had been deeply disturbed by what he'd witnessed at Guantánamo.

As it happened, the military-tribunal system was facing its greatest legal challenge yet. Civil-rights groups had appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, asking the justices to strike down the 2006 Congressional law authorizing its creation. The civil-rights lawyers presented the same argument they'd used when the Guantánamo detention camp had opened in 2002: the inmates were in fact protected under the U.S. Constitution and therefore had the right to challenge their detentions in federal courts, not just military ones.

In April 2007, the Supreme Court declined to hear the case, a major legal victory for the Bush administration. Nevertheless, at Cynamon's urging Abraham filed an affidavit with the Supreme Court, stating that the military tribunal system was unfair and biased. "What were purported to be specific statements of fact lacked even the most fundamental earmarks of objectively credible evidence," he affirmed. He described pressure from supervisors to reverse his decision after he determined there was no cause to classify an inmate as an enemy combatant. He described the personnel who were compiling the cases against defendants as "relatively junior officers with little training or experience in matters relating to the collection, processing, analyzing and/or dissemination of intelligence material."

A few weeks later, the Supreme Court did something it hadn't done in sixty years—it reversed itself and agreed to take on the Guantánamo appeals. Although the Court did not provide an explanation for its reversal, Cynamon believes that Abraham's testimony had a lot to do with it.

In June, the Supreme Court ruled that the military courts were unconstitutional. The decision was a rejection of the Bush administration's entire legal justification for the Guant√°namo detention facility. Connecting with Abraham, Cynamon says, was the "most marvelous example of serendipity I have ever had in my legal career."

Of the 779 prisoners who have passed through Guantánamo, only 223 remain. Most of the Brown alumni lawyers who have represented detainees have succeeded in getting some released. Other clients are still there.

Cynamon, for example, represented a client who successfully challenged his detention in federal court more than a year ago, yet he is still in Cuba. Cynamon claims it's now the Obama Justice Department that is delaying the release of an innocent man. "The Obama administration claims to have restored the rule of law," he says, "but in fact it is following the Bush playbook on Guantanámo to the letter."

Katznelson reports that in January, Gharani was ordered released after a federal judge in Washington, D.C., ruled that the government had relied on testimony from two unreliable witnesses when it had declared him an enemy combatant.

After leaving Cuba, Gharani returned to Chad, where he was at first treated like a returning hero, Katznelson says. But now, for reasons that he doesn't understand, the government of Chad has yet to issue Gharani his identification papers, which means he is unable to work, travel, or enroll in school. Katznelson says a cloud of suspicion still hangs over Gharani. "He is not able to rebuild his life," Katznelson says. "He's trapped in a different kind of prison."

Lawrence Goodman is the BAM's senior writer.