A few years ago in an introductory writing class I was teaching, a girl explained that she wanted to investigate the ways in which her generation, the first to grow up with the Internet, was unlike any other generation before it. Concerned that someone like me, adrift in his mid-forties, might not quite fully grasp her meaning, she supplied a helpful analogy: "For us, computers are like what cars must have been for you." The class exploded with laughter.

Not so very long ago, when I had gone off to college myself, I'd left the familiar world behind and dwelled there on campus, body and soul. Weekend bacchanals notwithstanding, it had been very much a monastic experience. Severed from home, I'd shed one layer of self after another, taken on new ideas and new practices, and by the end of those four years I had managed to become someone the younger me never would have imagined.

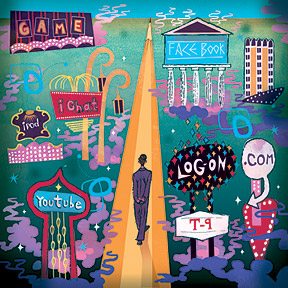

While I wouldn't suggest that college today doesn't have that same transformative potential, there's no withdrawing, not anymore. We're all connected all the time. Class ends and students are barely out the door before they're calling home or texting friends or surfing the web. Time for reflection is obliterated. They—and all of us—can end up living in a state of near perpetual distraction.

These game-changers are of course market driven. And so we are market driven. And increasingly we don't so much reveal character through beliefs or deeds as signal identity through the logos on our clothes and cars. But when students write—when they bear down and think hard—they enter a solitude, a silence, and in that silence they can follow each thought all the way through until finally a belief takes shape. That belief, tried and true, can form the basis of a conviction, something that can inform the way they go on to live their lives.

Any number of times I've spoken with students about the importance of writing. I've explained that it's integral to learning, that to write well you have to read well, and that to read well you have to think hard. Thinking hard is how we learn, and is how we contribute to the learning of others.

Writing also matters to life outside the academy, to life after Brown. And life can be very hard. Even when things go well for us and we succeed in softening the experience, the fundamental problem of self remains. What makes a life meaningful? The question brooks only so much delay. I like to believe that by teaching writing what I'm really doing is helping students find ways to face that question head-on, so that when they go out into the world, they can do good work and believe in the good work they do.

Douglas Brown is the director of writing support programs on campus.

Illustration by Gilbert Ford.