"How, Mr. Shesol, does one occupy a fox?"

I had to admit that I had never considered the question. I was aware, however, that it had been intended to make me squirm and, not incidentally, to make the hundreds of students in Salomon 101 erupt in laughter. It was also aimed at marching those of us enrolled in The Politics of the Legal System steadily toward an understanding of the issues raised by Pierson v. Post, a classic case concerning the "occupancy," or possession, of a fox that had been killed by a hunter. Ed Beiser's question succeeded in all three regards—just as he knew it would.

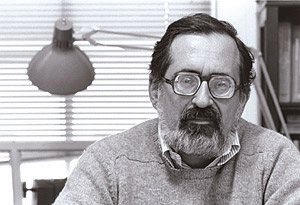

One of Brown's most feared and beloved professors, Ed Beiser died September 4, of Parkinson's disease. He was sixty-five. To call his teaching method Socratic was to deny its idiosyncrasies and, more importantly, the craft and consideration that had gone into developing it. Professor Beiser's approach well predated his mid-1970s enrollment at Harvard Law School, where he had gone not to teach but to earn a J.D. The Beiser method was equal parts Socrates, Maimonides, and Mort Sahl. He could be entertaining, challenging, inspiring, and riveting—all in a single lecture. He coaxed, led, and, it must be said, occasionally badgered his witnesses.

Still, Ed was not a showman, and this was not performance for performance's sake. He believed that we were there (and here) for a purpose. "We have the great intellectual luxury of picking the hard, interesting legal questions to study—of examining some of the most fundamental questions in life," he once told the BAM. His teaching method reflected his belief that life's biggest, toughest questions do not yield to cramming on the eve of exams. He required us to maintain a constant level of engagement with the material.

The Politics of the Legal System and its precursors were not pre-law classes. When Ed created Brown's interdisciplinary Center for Law and Liberal Education in 1977, he served notice that he did not hold the key to law-school admissions. As for students who might insist, regardless, on using the center as an opportunity to "play lawyer," Ed promised this: "We will beat them away with sticks." They showed up anyway, of course, and no doubt are better lawyers, judges, and policymakers as a result. Many will still tell you that one semester with Beiser taught them more of value than three years of law school.

In 1985, Professor Beiser became Brown's associate dean of medicine. He once delivered a lecture at Rhode Island Hospital with the title "Reflections of a Lawyer Who Likes Doctors." But what Ed really liked were ethical dilemmas—Hard Choices, as he called one of his most popular courses. His chief intellectual interest, I think, was neither law nor medicine but the moral and practical consequences of human action, inaction, interaction.

One of his colleagues recently told me that Ed would have made a good rabbi—and this was exactly how many of us, his student congregants, viewed him. Yes, it helped that he looked and sounded the part. But really, it was Ed's directness, his genuine concern, and his appreciation for the deep moral difficulties with which even young men and women must grapple, that made him far more than a professor to so many of us during his thirty-five years at Brown.

I remember sitting with him in his backyard on a sunny spring afternoon a week or two before my graduation. I had been to his office a couple of times that semester to revisit some question he had raised in class, but this meeting was social; I was stopping by to say thanks and good-bye. I found that he was not done with me yet. His face was impassive—the "mask" associated with Parkinson's disease—but his eyes were alert, conveying a range of reactions. And his questions, as ever, kept coming. Now they concerned my life plans and career goals, rather than some fine point of constitutional law. Seated in a lawn chair, beside a small table bearing a pitcher of iced tea, Professor Beiser administered one last exam before I went off to face whatever hard choices lay ahead.

A former speechwriter for President Bill Clinton, Jeff Shesol '91 is a partner at West Wing Writers, a speechwriting and communications strategy firm, and author of Supreme Power: Franklin Roosevelt vs. The Supreme Court, which will be published by Norton in March.