Environmental historian Karl Jacoby restores memory. Personal memories help fuel his work, and historical memory shapes it. If, as is often said, history is written by the winners, the reason is that winners control our collective memory. They determine which documents are preserved and honored, which incidents are forgotten, and which are important. "Violence," Jacoby has written, "may begin as a contest over resources, but it often ends as a contest over meaning, as the participants struggle to articulate what has happened to them—and what they have, in turn, done to others."

The problem is that, like the Communist officials in Milan Kundera's The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, this dominant narrative can airbrush out inconvenient facts and memories, particularly when it comes to the history of the American West. The newest generation of U.S. historians is for the most part engaged in unearthing these facts and memories and adding them to the storyline. Historians often discover these anomolies accidentally, while looking for something better known. Jacoby's first book, Crimes Against Nature: Squatters, Poachers, Thieves, and the Hidden History of American Conservation, began with just such a forgotten document, a letter sent by a Havasupai Indian to authorities complaining that since game wardens had begun patrolling his hunting grounds, deer seemed to have become less abundant, and he didn't understand why. "It's very rare," Jacoby says, "to find letters from Native Americans in the archives. Here was this forgotten voice, and I needed to understand why he was complaining about this game warden."

Jacoby's research for Crimes Against Nature led him to conclude that one of our most comforting narratives—the visionary creation of our national parks— is incomplete at best. The book fills in the social history of rural America that the history of conservation usually neglects. Crimes Against Nature, which won the American Historical Association's Littleton-Griswold Prize as 2001's best book on law and society, suggests that, while the parks may have been "America's Best Idea," as Ken Burns describes them in his latest documentary series, implementing that idea had important social costs to Native Americans and poor whites.

This matters because the vision of wilderness that underlies our national parks is one of ecosystems without people, and once it was encoded into law rural populations living within the parks had to be either displaced or rigidly controlled. The Havasupai Indian complaining about a game warden, for example, was really objecting to the presence of new game laws that overrode the hunting practices the tribe had been using for millennia. Using Yellowstone—our first national park—as an example, Jacoby writes, "The vision of nature that the park's backers sought to enact—nature as pre-human wilderness—was predicated on eliminating any Indian presence from the Yellowstone landscape." And: "Drawing upon a familiar vocabulary of discovery and exploration, the authors of the early accounts of the Yellowstone region literally wrote Indians out of the landscape, erasing Indian claims by reclassifying inhabited territory as empty wilderness." No wonder, as Jacoby writes later in the book, "conservation was for Native Americans inextricably bound up with conquest."

Jacoby's book was disquieting to many conservationists, particularly because it was published just as President George W. Bush was rolling back many environmental protections. "Keep this book away from officials in the Bush administration's Interior Department," one reviewer warned. But Jacoby insists that his job is to offer a fuller, more complex version of history, regardless of its political implications. "Environmental history grew up originally in the shadow of the environmental movement," Jacoby says, "and grew up writing the history of the environmental movement as very much a sort of cheerleader. My book and some others are an attempt at writing a somewhat more self-aware history of that movement. It doesn't help us not to have the full history."

If Crimes Against Nature implies that our history is inextricably tied to our mythmaking, Jacoby's second book, Shadows at Dawn: A Borderland Massacre and the Violence of History, published last November, ups the ante. What if the practice of history itself is biased? If history is based on documentary evidence and is primarily an analysis of known facts, what's a historian to do when confronted with populations whose documents are paintings on a cave wall or carvings on a stick? How can a historian accurately describe the facts of a massacre when the memories of its victims died with them? "No one," Primo Levi has written, "ever returned to describe his own death."

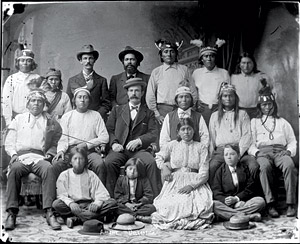

By telling his story from below, Jacoby portrays both Indians and whites with unusual insight and subtlety. Although Shadows at Dawn explicitly sets out to reverse the portrayal, in countless Westerns and many histories, of Apaches as ruthless, evil raiders, his bottom-up approach portrays whites and their motivations with surprising empathy. This is no small accomplishment. After all, the massacre's leaders were prominent Tucson citizens; one would be elected to the city's four-person governing council and become the local sheriff. Although the participants in the Camp Grant Massacre were arrested and tried, the jury deliberated just nineteen minutes before finding them innocent. Even the district attorney trying the case had been involved in some of the planning meetings for the attack on the Apaches.

Clearly, the Peace Policy hadn't changed many attitudes in the Arizona borderlands. In one particularly relevant irony, some of the massacre's participants would found the organization that later became the Arizona Historical Society, the main repository of the state's historical documents. There is still a park in Tucson named after one of the massacre's leaders.

By his own admission, Jacoby's book was a dark one to write, more so, perhaps, because it is not a simple moral condemnation of violence against Native Americans. Shadows at Dawn, which comes out in paperback this November, is an account of conflicting worldviews, of the way different cultures can look at the same physical landscape and read into it different, and often irreconcilable meanings. Jacoby asks not only how the Camp Grant Massacre could happen; he describes how the event became absorbed into the histories of the different cultures involved in it and how their memory of it helped shape those cultures afterward. He does this by adopting the novelistic device of narrating his story in chapters written from the point of view of each of the four cultures involved in the massacre as perpetrators or victims: Anglo-American, Mexican-American, O'odham, and Apache.

"For novelists," Jacoby says, "having four competing points of view is nothing new. But historians like to have a linear narrative." Historians study different points of view and integrate them into a singular story line, making broad, omniscient judgments along the way. "I wanted to try to tell the story using four different narratives. Because of this, there isn't really this sense of moral outrage, or at least it's not overwhelming. What you discover is how foreign and other the other groups seem to each of them. The absolute truth is found in the juxtaposition of all these realities."

Shadows at Dawn, then, is more William Faulkner than Zane Grey. The book reads like true tragedy, a collision of forces that seems inevitable, evidence of what the Princeton scholar William Howarth called "lucid madness" in his American Scholar review of the book. Jacoby's narrative is divided into three main sections. The first, "Violence," consists of four chapters, each tracing the broad sweep of history of these four cultures in North America; for the two Indian groups, the O'odham (also known as the Pima and Papago Indians) and the Apache (or the Nn–e–e–, as they are called in the book) this history extends back to their creation stories.

The technical and scholarly accomplishment of these chapters is remarkable. Because the historical documents come largely from the European cultures, the danger is that the chapters about European descendents would be richly detailed while those focused on the Native American groups could seem sketchy by comparison. But Jacoby has dug deep, teasing out references to Native culture and testimony in Anglo and Spanish documents, and tracking down O'odham "calendar sticks," ribs of saguaro cactus on which important yearly events were noted by a village historian. Early anthropologists had dismissed the events recorded on calendar sticks as village gossip, but Jacoby uses them as an indicator of what mattered most to villagers during particular years. For example, the O'odham found Mexico's sale of their land to the United States in the 1850s so unimportant that calendar sticks of the time failed to note it at all, instead recording more immediate threats. "The Apaches came to steal horses and brought a live vulture with them," one stick noted. "They were discovered and several killed."

"Justice," the second and briefest section of the book—it's only eight pages long—describes the one-day trial of the massacre's 100 participants. Because the Apaches in the canyon were under the protection of the U.S. Army at the time, the region's military commander believed the massacre to be an act of war against the United States, but, as Jacoby writes, "to many of the region's residents, it was not clear that the killing of Apache women and children in Aravaipa Canyon constituted a crime at all."

The third section of Shadows at Dawn, "Memory," re-turns to the four-points-of-view structure of "Violence" by tracing the massacre's aftermath up to the present day. Summing up his approach, Jacoby writes, "We can judge these accounts for their faithfulness to an always incomplete historical record, and we can acknowledge that all attempts to narrate the past are at once processes of remembering and forgetting, in which the creation of a coherent story is achieved by prioritizing certain events over others. But we cannot confine ourselves to a single one of these narratives without enacting yet another form of historical violence: the suppression of the past's multiple meanings."

For the O'odham, first contact with Europeans meant disease and competition for scarce water. Yet the O'odham sometimes allied themselves with the Mexicans, and, later, the Americans, against a common enemy, the Apaches, who as hunters and opportunists, survived by taking what they needed from others, whether horses or livestock. This was how the Apaches had always lived, by their wits, and Jacoby theorizes that when they first encountered horses or other ranch animals that had gone feral, the Apaches saw the displaced livestock as a new type of game.

What's clear from Shadows at Dawn is how remote was the possibility that such radically different cultures could ever find much common ground. What seems truly extraordinary is how the Apaches and other Native Americans have managed to survive to this day, given the overwhelming transformation their world underwent. O'odham and Apache society, for example, was based mostly on family ties. The idea of a king or a president, of a ruler of all people across a continent, was completely incomprehensible. Similarly, when the U.S. Army believed it was signing a treaty with a tribe, the Apaches believed they were signing an agreement valid only for their band. What other families or villages did was neither their concern nor under their control. Even the concept of tribe seems in this case to have been an artifact of a government trying to impose an order that felt familiar and close to its own.

Each of the four cultural groups Jacoby describes saw the others as the true barbarians. Because Apaches took what they needed without regard to private property, Mexicans and Americans saw them as lawless. Native societies, meanwhile, had elaborate rules about battle and revenge and justice. Killing was followed by elaborate purification ceremonies, during which the attributes of the killed were incorporated into the spirit of the warriors. (In fact, the Camp Grant Massacre victims were mostly women and children because the men were on such a purification ritual elsewhere in the canyon at the time.) That whites, on the other hand, hanged people by the neck and thought little of it afterward was, to Apaches, a sign of true barbarism.

The arid and violent landscape along the Arizona-Mexico border is a far cry from the green and wooded hills of Concord, Massachusetts, where Karl Jacoby grew up. Jacoby attended public schools in Concord and might have grown up to be like any other suburban kid—if it hadn't been for his grandfather.

Jacoby's maternal grandfather grew up in Queens but developed lung problems as he aged and sought out a dry climate. He wound up moving to a small farm in Alamos, Mexico, at the southern end of Sonora province. There, Jacoby's grandfather and grandmother lived in an adobe house and raised much of their own food. Chickens scratched dirt in the yard. "I think of him a lot as the old gringo in the Carlos Fuentes novel," Jacoby says of his grandfather.

Beginning when he was two years old, Jacoby and his family used to visit relatives in Phoenix and then make their way south across the border into Mexico. It was, he says, less like traveling across the border of two countries than traveling back through a century. He'd visit for two weeks at a time, attending the local school in Alamos. "It was a classic one-room school," he recalls. "Sometimes there were two of us to a desk. It seemed very much like a school from the 1930s."

It was odd, he says, to "parachute into these schools and then leave again." In grammar school, he had difficulty joining the local games. Wooden tops set spinning with a string were all the rage, and Jacoby fumbled unsuccessfully to join in. In junior high, his classmates assumed that as an American he would be a first-rate basketball and baseball player, but in fact he was a mediocre athlete, except for soccer. He describes himself as a "studious, bookish kid."

By the time Jacoby entered high school, his grandfather had died, and his parents believed the weeks away from school in Concord were too disruptive, so the trips to visit his grandmother in Alamos became less frequent. But they had created a strong impression that would help later determine Jacoby's choice of career and even his subject matter. The trip through time, the stories about Geronimo and other Apaches, the contrasts between Mexican and Southwestern Anglo culture—these he felt compelled to try to understand. "Shadows at Dawn," he says, "is that little kid trying to understand that landscape."

His first year on campus was difficult, as it is for many Brown students. "I found my first year pretty hard academically," he says. "I thought that with my academic background I'd do okay, but I found that in order to do well I had to work much harder than I had in high school." He became a history concentrator, taking courses from such professors as Jim Patterson, Naomi Lamoreaux, Howard Chudacoff, and the late Jack Thomas. (To Jacoby's regret, he never took a course with Gordon Wood.) In his spare time, he became a disc jockey at WBRU and met the woman who would become his wife, the future novelist Marie Myung-Ok Lee '86. Under the supervision of Chudacoff and education professor Herman Eschenbacher, he wrote his honors thesis on the history of Rhode Island education.

After Brown, Jacoby considered graduate school, but instead moved to New York City and took a job as an editorial assistant for Farrar, Straus and Giroux (FSG). There he read manuscripts, wrote reports on them, and helped shepherd some through production. Because he was one of the few people at FSG at the time who could read Spanish, he helped with the production of novels by Carlos Fuentes and Mario Vargas Llosa. It was a heady time. David Rieff worked in the office, and his mother, Susan Sontag, sometimes dropped in. Another fellow editorial assistant was Rick Moody '83, who was writing his first novel, Garden State. Jacoby played on the publishing house's softball team, and among the young authors on the team was novelist Jonathan Franzen.

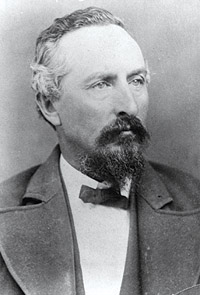

Most significant, though, was Jacoby's work at Hill & Wang, FSG's academic imprint. There Jacoby met the pioneering environmental historian William Cronon, who was then at Yale. Jacoby had read Cronon's classic work, Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New England, while he was at Brown, and in talks with Cronon, he began to realize that it might be possible to have a professional life focused on landscape as an element of history.

Working at FSG, Jacoby says, demystified the process of writing a book, so much so that he decided he wanted to write one himself. "I realized from talking to Bill [Cronon] that there was this growing interest in the West and the environment. And because my childhood experiences had shown me things that were not in the history books, I felt they had given birth to a potentially serious subject for history." He decided to apply to graduate school and was accepted to study with Cronon at Yale. Marie Lee, who had been working on Wall Street, quit her job to write full-time, and the couple moved to New Haven.

Jacoby received his PhD in 1997. His dissertation was the first draft of Crimes Against Nature. The following year, as he rewrote his book, he worked as a visiting professor at Oberlin College, and the year after that, he became an assistant professor of history at Brown. Jacoby believes that, intellectually, he has come full circle at Brown. He discovered environmental history as an undergraduate studying with Jack Thomas, and he believes he has returned to help the discipline mature and develop. Jacoby also takes great pride in his development as a teacher. He has worked hard to overcome his natural shyness and likes to note that he has won the William G. McLoughlin Teaching Award for Excellence in the Social Sciences. Last year 140 students enrolled in his environmental history course.

Shadows at Dawn has already collected a few history prizes, and it is under consideration for more this fall. In May it won a Special Recognition award at the annual RFK Book Awards in Washington, D.C., narrowly missing out on the top prize, which was given to The New Yorker's Jane Mayer for The Dark Side, her report on the War on Terror. In September, Jacoby learned that the American Society for Ethnohistory had chosen Shadows at Dawn as the best new book in that field. The reviews have also been good. The novelist Larry McMurtry, while praising the book, including its detailed glossary, in the New York Review of Books gushed, "I once wrote about the Camp Grant Massacre myself and think now that I'd rather have Professor Jacoby's glossary than my whole essay."

Meanwhile, Jacoby has already begun his next project, which will again focus on history along the U.S.–Mexico border. The subject is less grim, he says, adding that he could not follow Shadows at Dawn with another depressing subject. The book will stay with him, of course, though its effect on altering our perceptions of the American West may be confined to academic circles for the time being.

During the final stages of writing the book, Jacoby traveled to Aravaipa Canyon to see what remains of the massacre site. Nearby are the Aravaipa Villa RV Park and a branch campus of Central Arizona College. Most of the nearby land is owned by the federal Bureau of Land Management and the Nature Conservancy and is managed as a national wilderness. The actual massacre site is not a part of this land—tribal historian Dale Miles would later take him there—but the vast wilderness area, he writes in Shadows at Dawn, "has helped solidify public perception of Aravaipa as untouched nature." When he asked the ranger at the entrance to the canyon about the massacre site, the man said, "Far more people come out here for nature than for history."

Thanks to Jacoby, the memories of the dead will linger for another generation, for a few of us at least.

For information about Shadows at Dawn, including scans of of documents Jacoby used to write it, click here. Norman Boucher is editor of the BAM.