If you think scholarly research and hip-hop music don't go together, you don't know Tricia Rose '87 AM, '93 PhD. Rose, a Brown professor of Africana studies, knows her Biggie Smalls, and her Eazy-E. She also knows her history. Rap and hip-hop, she believes, are serious forms of cultural revelation that offer a window not only into the streets and basketball courts that spawned them, but into broader patterns of social exploitation and consumer culture.

When, in the first line of her new book, The Hip Hop Wars: What We Talk About When We Talk About Hip Hop—and Why It Matters, Rose observes that "Hip-hop is not dead, but it is gravely ill," she writes as both a fan and a social critic. Rose believes that what began as a spontaneous form of African American cultural expression, built from the only musical tools available to poor urban youth, has become commercialized into a dangerous commodity. And what a commodity it is: Despite slumping sales in the music industry, last year's top hip-hop earner, 50 Cent, raked in $150 million. In 2004, when rap music and its accompanying cultural accessories—sneakers, jewelry, Pimp Juice—generated more than $10 billion dollars, Forbes reported that the industry "has moved beyond its musical roots, transforming into a dominant and increasingly lucrative lifestyle."

As Rose argues in books such as Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America and last year's The Hip Hop Wars, rap and hip-hop are so important that we underestimate their cultural impact at our peril. She is one of the few scholars to take this music seriously, and in her scholarship and public speaking she has issued a challenge to those on both sides of what she sees as the hip-hop divide. Cornel West has called Rose "the distinguished dean of hip-hop studies." "Above all else," says the African American media maven Tavis Smiley, "Tricia Rose is real."

What the record industry is selling, Rose argues, is not music, or fashion, or television shows like Pimp My Ride or Flavor of Love, it's blackness. It's a very particular and narrow concept of blackness that has little to do with real people and everything to do with valorizing violence, drugs, sexism, and materialism. It's a sort of modern-day minstrelsy: commercial hip-hop artists, with help from record companies, package themselves into what they think white people want to hear, and then sell it to them. "Artists are getting rich", Rose says, "but at what cost?"

One major cost is the message sent to young black people as they learn to understand their place in the world and the options available to them. Rose's husband, Andre Willis, a Yale assistant professor of the philosophy of religion, contrasts hip-hop in this sense to jazz. "When you're talking about jazz," says Willis, "ultimately, on my read, you're talking about something that affirms the fundamental unity of humanity. When you're talking about rap, you're talking about something which accentuates and acknowledges that which divides us." As an African American man, Willis knows what racism can do to the soul of a person and a community. So, yes, he acknowledges, "It moves me. But they're unhealthy ways of moving me. They don't end up reducing my rage, helping me love better."

For Rose, this is the essential problem facing hip-hop: how can a music that has always been an outlet for black aspirations and frustrations, for its joys and sorrows, return to a place where it's also a force for social change? "I come from very F-U stock," Rose says with a laugh. "But you can't just say F-U. You gotta say yes to something." In other words, she wants to know, how can hip-hop make people love better?

Black Noise, published in 1995, is the work of a young, idealistic academic. Adapted from Rose's doctoral dissertation, it is a paean to rap music and all its political possibilities: "Worked out on the rusting urban core as a playground," Rose writes, "hip-hop transforms stray technological parts intended for cultural and industrial trash heaps into sources of pleasure and power.... Hip-hop gives voice to the tensions and contradictions in the public urban landscape ... and attempts to seize the shifting urban terrain, to make it work on behalf of the dispossessed."

The book was a seminal work. Other African American musical forms, such as jazz and blues, had long been taken seriously by scholars, but until Black Noise rap was considered a passing fad, cultural fluff not worthy of scholarly attention. The book went on to win the American Book Award from the Before Columbus Foundation. Black Issues in Higher Education called it one of the top twenty-five books of the twentieth century. The Village Voice called it "necessary reading ... for those who love hip-hop's rhymes and reasons."

But somewhere along the line, Rose found that the music had turned on her. Take "Gin and Juice," the irresistibly catchy 1992 smash hit by rappers Dr. Dre and Snoop Dogg. "Once I really listened to the words and thought about the story being told," Rose writes in The Hip Hop Wars, "it was hard to know what to do: Respond to the funk and ignore the words, or reject the story and give up the funk that goes with it. The moment I realized that I was being asked to give myself over to the power of the funk—which in turn was being used as a soundtrack for a story that was really against me—was a very sad day for me."

The soundtrack of Rose's story starts with stacks of 45s. Raised until she was nine years old in a Harlem tenement where her mother had to organize rent strikes to get the heat turned on in the winter, Rose would save up her quarter-a-week allowance money to buy the newest singles by James Brown; Earth, Wind & Fire; the Stylistics; and Parliament-Funkadelics.

Rose is painfully aware that her upbringing could easily be romanticized by those who (to use the name of a mid-nineties rap group) are invested in the Thug Life. But she's not interested in that kind of street cred. In fact, she would rather not talk too much about her childhood at all. "I hate the big violin thing," she says. "I am so not the personal storyteller."

When she interrupts herself to say this, she is talking about her white mother's parents, who cut off contact with their daughter when she married the black man who would become Rose's father. Until the day her grandparents died, Rose says, they were never in the same room as her father, the man who saw to it that his kids had every opportunity that he had been denied. Still, she says, "This is classic. It's really not a big deal."

In 1970, when Rose was nine, the family moved to Co-op City, a brand-new housing development in the northeast Bronx. Her brother Chris, five years her senior, remembers the move as "a revelation." "You could go out and you could actually be safe," he says. "You could ride your bike around without people trying to steal it from you all the time."

This was a pivotal time in New York City history. In the name of urban renewal, cities were using federal funds for slum clearance razing entire neighborhoods and turning them over to private developers to build massive housing complexes. Many prominent voices had been criticizing this approach for years: Jane Jacobs had published her Death and Life of Great American Cities in 1961, and in 1963 James Baldwin had famously said, "urban renewal means Negro removal"—but the devastating results of that policy had not yet reached their peak. Working-class New Yorkers were still hopeful about upward mobility. Like the Roses when they moved out of Harlem, "everybody who could get out of these bad neighborhoods did," says Chris Rose. "Co-op City was like the first stop. Everybody was pretty like-minded, with similar aspirations and families." The multiracial development was still under construction when the family moved in, and Chris Rose recalls that the residents were all striving together. "Tricia just blossomed in that environment," he says. "This kid's running around, making friends left and right."

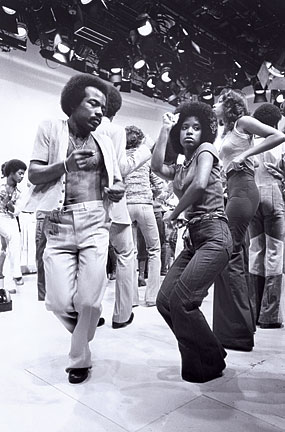

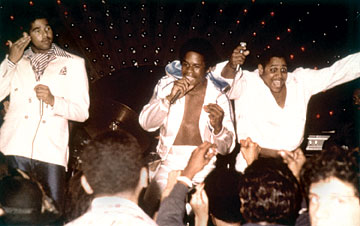

To spend a day with the adult Tricia Rose is to see this scrappy, outgoing kid in action. Today she is at the New York City studios of VH1, where she will be interviewed for a documentary about the pioneering black music show Soul Train, which first aired in 1971. Sitting on the set in a director's chair, her face framed by loose brown curls, Rose manages to exude both warmth and toughness. She is exceedingly gracious and never talks down to people—even when she's schooling them. She will learn the names of everyone she meets today, from the makeup artist who prepares her for the camera (Christopher), to the cab driver who takes us to lunch (Donnell), to the waiter who serves us there (Daniel). She has an easy rapport with the documentary's producer (Kevin), even after she discovers he produced several music videos for the slain Los Angeles rapper Tupac Shakur—exactly the guns-and-drugs type of material Rose excoriates in The Hip Hop Wars.

With the cameras rolling, Rose shifts gears easily between her personal memories of Soul Train, the historical and sociological context for its popularity, and the political implications of the first public space on television for black youth culture. She talks about white flight and Negro removal. She talks about Afros, poking fun of her teenage preoccupation with having "the biggest Afro with the least number of dents!" She talks about disco and message music and the significance of the train metaphor in African American history.

"This is really good," Kevin tells her while the cameraman changes tape. "You use some really pretty words, too. I'm going to have to Google some of those words."

Rose just laughs. They had just been talking about the anagram game that was featured each week on Soul Train, and she teases Kevin about it. "We gotta get you a Scramble Board."

As she recalled on the set that day, ten-year-old Tricia Rose watched Soul Train in her new bedroom in Co-op City, and it "just blew your head open." Until Soul Train, African Americans were rarely on television except as a "nightly news problem," as Rose describes it now. There was no Cosby Show. There was no Gwen Ifill, no Oprah Winfrey. "If you saw a couple of black artists on Dick Cavett, it was unusual," she says, but on Soul Train black kids were dancing, hanging out, and making music in the name of exuberance and fun. "It was liberating," she says.

She wasn't able to articulate it quite this way yet, but even as a young girl, Rose was aware that her identity was complicated and life wasn't always as it seemed. Her white mother and her relatively light skin, for instance, had made her the object of suspicion among other children in Harlem. "There were a lot of kids who were mad about what it suggested to them," Rose recalls, "that it was somehow a privilege I didn't deserve. I remember being acutely aware of both the injustice of the interpretation of me, but also that I had advantages because I had two parents. A lot of them didn't."

When their parents secured scholarships for Tricia and Chris to attend the Dalton School, on Manhattan's upper East Side, Rose's sense of herself as both an insider and an outsider—a black, white, poor, rich, prep-school girl from the hood—was solidified. The kids in her neighborhood said she was the lucky kid who goes to prep school. "Scholarship? They could care less. To them I was rich because I went to prep school." On the other hand, "the rich white kids saw me as the scholarship kid."

While many of her classmates could walk to school, the Roses had to rise at 4:45 a.m. to be on the subway by six and at school by 7:30. Once, on a weekend trip to a classmate's country house, Tricia got lost on the way from her bedroom to the kitchen. When she finally found an intercom, "I had, like a rescue team," she recalls with a laugh. To a girl for whom luxury was having her own bedroom, the opulence was "just astonishing."

"It's not a happy thing about your childhood, to say you were always conscious about being on the outside, but there's a sense in which that's true," Rose says. Underlying these early lessons in what it means to belong was Rose's natural disposition, "not really to be in something, but to kind of watch it," as she describes it. "I'd go out dancing and be thinking about the politics of space. It's just how I came into the world." This cerebral, analytic approach, combined with a profound capacity for empathy, underlay her intellectual and emotional development. She does get angry about what she sometimes observes, and she will call people out for their ignorance, but she doesn't blame them for it. She knows that the rich kids at Dalton were just as much a product of the racial and economic system of the time as she was.

While at Dalton, Rose fell in love with basketball. A ruthlessly competitive player—she is a member of the school's hall of fame—she practiced her game during the weekends on the courts near Co-op City. It was here that the soundtrack to her life took its most significant turn. This was the era of the boom box, that plastic-and-electronic behemoth that teenagers would hoist onto their shoulders as they paraded around the neighborhood. They would always stop over at the basketball courts. Equal parts sports venue, community center, and performance space, the courts crowded with "people coming up with rhymes, and people trying to bust a move, and writing in their draft books, Rose recalls."

This was a dire time for New York City. Years of white flight and the decline of the manufacturing sector gutted the city's tax base, leading to a downward spiral: those who could leave, did, and those who couldn't were left with no job prospects and a frayed safety net. (The Daily News's famous headline "Ford to City: Drop Dead" hit newsstands in 1975.) The construction of the Cross Bronx Expressway and decades of slum clearance programs had displaced hundreds of thousands of working-class families, disrupted social support networks, and led to the abandonment of entire neighborhoods and the widespread arson that became the very symbol of the South Bronx.

Out of this wreckage, Rose argues in Black Noise, hip-hop was born. "At a time when budget cuts in school music programs drastically reduced access to traditional forms of instrumentation and composition, inner-city youths increasingly relied on recorded sound.…[H]ip hop artists transformed obsolete vocational skills from marginal occupations into the raw materials for creativity."

As Rose details in Black Noise, rather than work as an auto mechanic, Jamaican DJ Kool Herc used his trade school skills to build his massive Herculords speakers, which revolutionized the kind of backbeats that could be played outdoors. As Rose witnessed on the basketball courts in her neighborhood, without community centers and music venues—which had been shuttered and bulldozed by the thousands—new artists performed outside. "Early DJs would connect their turntables and speakers to any available electrical source, including street lights," Rose writes, "turning public parks and streets into impromptu parties and community centers."

It was at these parties and on these basketball courts that young, urban, poor kids of color—often children of immigrants who watched their parents' dreams of a better life wither on the vine—had their say. With rapping and rhyming and break dancing and graffiti, they turned their pent-up frustrations and anger and hope into something beautiful. Hip-hop culture, born of society's neglect, became a source of "communal pleasure," as Rose writes. It also gave young people the space to talk back, as when, in 1989, the rapper KRS-One used his music to point a finger at the police and ask, "Who Protects Us From You?"

Rose was a senior in high school when the Sugarhill Gang's "Rapper's Delight" climbed to number thirty-six on the pop-music charts, becoming the first major rap hit. Before then, Rose says, "I just thought [rapping] was like Double Dutch or something. You hang out, you talk junk, and you rhyme. Then when 'Rapper's Delight' came out, I was like, 'Huh. It's on the radio.' The radio is like where real music was. How the heck did it get over there? It's like it went through this magical Wizard of Oz thing."

Even after Rose left the Bronx for Yale, she kept a close eye on emerging hip-hop culture. She wrote her senior thesis about rap music. When she graduated and got a job at the New Haven Housing Authority, she would still go to the library after work and read Billboard and think about hip- hop. "Every other music that I had been invested in had a huge history: R&B, classical, jazz, blues, funk, soul," she says. "This thing shows up in my lifetime, while I'm a teenager, and then becomes a huge phenomenon. I was stunned. How did this happen? And what happens to it, in this process? That's what really fascinated me."

Still, after Black Noise, Rose says she felt done: "I didn't want to write another book on hip-hop." It was during this period of intellectual searching that she met Willis, whom she credits with helping her achieve a profound shift in thought, a movement, as she puts it, from diagnosis to vision, "from what is wrong to what is wrong and what is right."

Despite this development, Rose hasn't let go of the anger toward the system that drove her earlier work. "I'm still pissed off about it all," she says. "History and racism and sexism. Economic inequity." The difference is that now she asks herself, "What do you do with that anger? It really will kill you. Yeah, you fight for justice, but you gotta live around in the meantime." How do you do that? "It's all about interpersonal relationships," she says, "how you craft your relationships with other people. That was an intellectual question for me."

Her 2003 book, Longing to Tell, dedicated to "believers of justice in intimacy," is a compilation of the narratives of twenty black women as they talk in their own words about their intimate relationships. Reading the voices of these women—young and old, immigrant and U.S.-born, gay and straight—you can almost watch Rose developing and honing in on her current intellectual preoccupation with intimate black social spaces. "We know that structural oppression—whether it's gendered, class, racial—impacts people as individuals," Rose says. "But the response to that is not always a direct response. It's about how you craft relationships that create buffers. I'm interested in the nexus between how personal relationships can add another corrosive level—how it can be internalized, to some degree—but it can also be a place of healing and safety and alternative comfort." From the stories of Sarita, struggling to make her boyfriend, Malcolm, understand that a man who catcalls on the street should apologize to her, not him ("as if I'm Malcolm's property," she says), and Linda Rae, who was diagnosed with HIV after years of drug addiction and prostitution, the book gives equal weight to the small slights and the big blows, the everyday comforts and the most profound of connections.

As Willis says, "What I think she's asking is, 'How can we do justice, not only in intimate spaces in terms of couplehood, but how do our intimate spaces, our home lives, affect justice in the wider scope? How does love at home affect love in the world, and vice versa?"

In 2001, after the black feminist theorist bell hooks—a fierce academic with a razor-sharp mind—published her book of essays, All About Love: New Visions, the chatter among some scholars, as hooks herself pointed out at the time, was "bell is getting soft." Rose knows exactly what hooks was going through—and why her project mattered. Toni Morrison's 2005 novel, Love, picked up the same thread. "Love is an incredibly political act," Rose says.

These issues also drive Rose's next project, a study of intimate justice in the works of several writers and artists. The book is still taking shape but will include chapters on Lorraine Hansberry's A Raisin in the Sun, on James Baldwin, and on the music of such neosoul musicians as Michelle N'degeocello and Erykah Badu. Songs like Badu's 1997 "Tyrone," in which Badu takes down an immature boyfriend who doesn't pull his weight, bring to the forefront what Rose calls "the relentlessly personal, intimate black social sphere."

Rose sees works like these as an alternative to what rap and hip-hop have become. The combination of political awareness and musical innovation that Badu embodies in "Tyrone"—the very characteristics that originally inspired Rose about rap music—have been less and less in evidence over the last decade. Hip-hop no longer talks about such politically important issues as police brutality and black power. In fact, it seems increasingly to be doing the opposite: promoting the thug life of selling drugs and exploiting women, of demeaning education and making as much money as possible, no matter the personal cost.

Finally overcoming her reluctance to revisit the subject, in 2007 she sat down to write The Hip Hop Wars. Somebody has to be willing to say these things, Rose says. Someone "who is not getting paid by the industry, who doesn't expect to ever get a dollar from them, who doesn't care if they call me names. I'm old enough, you know, I really don't care. They can hate me. Young people could never talk to me again. But I'm convinced that what I'm saying is in the spirit of love and possibility, and if you can't see it, I love you anyway."

The book levels its criticism at both sides of the debate. Rose certainly holds rappers to account. She sounds profoundly disappointed and sad when she identifies "hip-hop's commercial trinity of the gangsta, pimp, and ho." "Isn't it hypocritical," she writes, "for artists to glamorize their history of drug dealing—deriving their earnings from endless tales about being gangstas who, for the most part, die young or spend most of their lives incarcerated, and pimps who revel in and exploit the objectified bodies of black women strippers and prostitutes—and then use the monies generated from perpetuating these images to support stay-in-school efforts and bone-marrow drives?"

But hip-hop's haters don't get a free pass, either. Rose argues that critics like Bill O'Reilly (who once compared Ludacris to Pol Pot) are short-sighted at best, disingenuous and racist at worst. Their "blatantly selective application of worries about violence" rings rather hollow, she points out, when they reserve these worries almost exclusively for art produced by black people. "A vivid example of this," she writes, was when George W. Bush "said it was 'sick' to produce a record that he said glorified the killing of police officers" and then gladly accepted the campaign endorsement of Arnold Schwarzenegger, "whose character in the movies Terminator and Terminator II: Judgment Day kills or maims dozens of policemen." Again and again, Rose cuts to the quick with the book's key insight: that when we talk about hip-hop, what we're really talking about is "poor, young black people and ... the context and reasons for their clearly disadvantaged lives." Hating hip hop, in other words, is really a way of blaming the black community for its problems, and sidesteps the positive steps that we could be taking to address them.

Despite its bellicose title, The Hip Hop Wars is, in the end, a book about love. But it's a more complicated, grown-up love than the love of hip-hop in Black Noise. As Rose explains in the last chapter of the new book, Black Noise was a work of affirmational love: the kind of unconditional support that "affirms us fundamentally," no matter our flaws. Her new outlook has expanded, crucially, to include transformational love, "a love that pushes us past our comfort zone, that demands we wrestle with standards and challenges growth in the interests of [our] well-being."

More than street cred or violence, more than pimps and hos and guns and drugs, Tricia Rose is here to tell you that it's love that keeps it real.

Beth Schwartzapfel is a BAM contributing editor.