The first time I met the Prophetess of the Bear Market—that would be Meredith Whitney— was also the first time in my fifteen years as a journalist covering Wall Street that a stock market analyst had invited me to sit in on one of her client gatherings.

Analysts are not risk takers by nature, especially when dealing with the press or the public. They hide behind mushy-mouthed stock ratings like "market weight" or "market underperform." They'll issue earnings-per-share estimates a few nickels below consensus and then pat themselves on the back for going out on a limb. Be too positive about a stock, they worry about opening themselves up to mockery. But be too negative, and maybe the company's CEO (or CFO or regional manager) stops returning their phone calls.

Oftentimes, the only way a hedge fund or mutual fund manager ever hears anything pointed or unvarnished from a Wall Street analyst (and God help the mom-and-pop stock buyer who doesn't know how the game is played) is by attending private meetings like the standing-room-only confab Whitney let me sit in on back in May of 2008.

At the time, I was profiling Whitney for Fortune magazine, where I work. Whitney—a bank analyst then employed by Oppenheimer & Co. and now out on her own as head of the Meredith Whitney Advisory Group—had made a name for herself in the fall of 2007 by digging through Citigroup's leaky balance sheet and correctly deducing that it would be forced to cut its once-sacrosanct dividend. She followed up her Citi call by raising similar concerns about other financial firms, which invariably led to plunges in their share prices.

I went into that meeting between Whitney and about seventy-five of her money-manager clients convinced that she would let something slip that she never would have told me in a regular interview. I had it in my head that she might have let her guard down with me—perhaps because of our Brown connection.

Well, I was wrong. One of the things I'd soon learn about Whitney is that there are no shades of truth with her. She'll tell journalists exactly what she tells hedge fund managers (though her clients always hear it first) because she knows she is right and always has the data to prove it.

It's easy for someone who sees Whitney on CNBC to get distracted by the blonde hair and stylish wardrobe and dismiss her as the flavor of the day. But behind the made-for-TV facade is a true numbers wonk whose level of conviction is off the charts because the time she puts into her job is too. Whitney usually works seven days a week, and I've received enough crack-of-dawn e-mails from her to worry—okay, to know—that she gets more done before 10 a.m. than I do all day.

My editors at Fortune wanted me to explain how on earth a little-known-name analyst from a second-tier firm could be stirring up such trouble for America's leading banks. The end result was an August 2008 Fortune cover story on Whitney in which she opined that subprime mortgages were just the tip of the toxic debt iceberg (check), that the economy was about to tip into a deep recession (double check), and that the banking crisis was, in her words, "far, far from over" (no, she doesn't have a crystal ball, at least none that I ever saw).

Indeed, Whitney has been so right so often about the biggest financial meltdown since the Great Depression that calling her the most important Brown alum on Wall Street would—with apologies to mutual fund manager Chuck Royce '61 and former Oppenheimer CEO Stephen Robert '62—be selling Whitney far too short. CNBC simply stated the obvious last December when it declared her "Power Player of the Year." And quite frankly, it's hard to think of any big name on the Street other than Whitney who emerged from last year's bloodbath with his or her credibility not just intact, but enhanced.

Simply put, at age thirty-nine, Meredith Whitney has more sway over the stock market—over your 401(k), your mutual fund, your pension—than any other analyst or money manager on the planet.

It all started with her call on Citigroup. From today's vantage point, predicting a dividend cut by a big bank might not appear to have been terribly gutsy. Trust me when I tell you it was. Dividends are a key draw for bank-stock investors, and Citi was the sacredest of sacred cows. Back then, postulating that Citi would have to cut its dividend was akin to claiming that the New York Yankees have to trade Derek Jeter in order to raise cash. It sounded preposterous—particularly coming from an analyst few investors had ever heard of.

And yet three months after Whitney came out with her October 2007 call, Citigroup did just as she predicted. The dividend cut turned out to be the first of four that would eventually pare the Citi's quarterly dividend from fifty-four cents a share down to zero. It wasn't long before CEO Chuck Prince was shown the door by Citi's board of directors.

Soon Whitney was broadening her targets, raising frightening questions about not just one or two banks but the health of the whole financial system. She saw what others did not, namely that the explosive growth in mortgage lending from 2002 through 2006 was based on faulty premises. One was that the average U.S. home prices wouldn't decline because they hadn't before—at least not since the Great Depression. Another was that no matter how exotic the mortgage product, lenders could accurately gauge delinquency risk by using FICO credit scores, which are supposed to measure the likelihood of a borrower defaulting on a loan.

Whitney argued that shoddy mortgage underwriting standards—aided and abetted by credit-rating agencies that kept awarding triple-A credit ratings to bundles of questionable loans—had created a ticking time bomb on bank balance sheets. Mass layoffs in the financial sector were inevitable, she said. Of greater concern to Main Street: Whitney believed that the housing market—already in steep decline—had much further to fall.

Such dire talk was nothing new for her. Whitney was the first Wall Street analyst to sound the alarm loudly about the subprime mortgage mess, writing in 2005 that "low equity positions in their homes, high revolving-debt balances, and high commodity prices make for the ingredients of a credit implosion" that would devastate low-income homeowners. As I wrote in Fortune, her 2005 report didn't turn Whitney into a star—though it probably should have—but it did land her an invitation to present her findings to the FDIC.

What Whitney didn't fully appreciate four years ago was how the proliferation of teaser-rate mortgage products with minimal or no down payments would transform high-credit-rating borrowers into subprime credit risks. Many prime customers who took on mortgages with 10 percent or lower down payments are now "performing closer to subprime," she wrote in a December 2007 report. The reason: a borrower who is upside down in his mortgage—i.e., the size of his mortgage is greater than the value of his home—is likely to make car and credit card payments before writing the monthly mortgage check. "The hierarchy of payments has totally shifted," Whitney says.

When Whitney started pointing this out, the market shuddered. Every time she downgraded a UBS or Lehman Brothers, their stocks would go tumbling, and she'd be deluged with angry calls and e-mails. She even received a death threat. In fact, Whitney was moving markets with such regularity that when doomed investment bank Bear Stearns & Co. started circling the drain in March 2008, Whitney decided against piling on. She feared (with good reason, in my judgment) that doing so would have resulted in her being blamed for Bear's demise.

Based on their questions, the money managers at that May 2008 meeting desperately wanted Whitney to tell them it was safe to start buying stocks again. No such luck. "What's ahead is much more severe than what we've seen so far," she told them, casting a pall over the room. She scoffed at bank CEOs who claimed that the worst of the credit crisis was behind them or that they wouldn't have to take even bigger losses on mortgages and other bad loans. She reiterated her predictions of enormous losses in the banking system—losses far greater than those being forecast by other bearish bank analysts. When asked by one shell-shocked money manager whether she harbored any doubts about her outlook, Whitney would concede just one. "While my loss estimates are much more severe than those of my peers," she offered, "my biggest concern is that they're way too low."

Saying such things about your own industry takes nerve. Whitney's sister, Wendy Taylor—another Brunonian, class of '88— says Meredith has always been something of a happy provocateur, whether it was arguing with her teachers about school assignments or browbeating her parents into letting her have a paper route at the tender age of eight. A self-described "route baron," Whitney eventually grew her delivery earnings to $200 a week by buying up other kids' paper routes. Warren Buffett is another former paperboy made good, and Whitney says that when she met Buffett last year, the Berkshire Hathaway chairman immediately started peppering her with questions about her tips and delivery strategies.

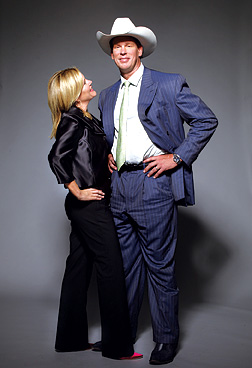

Whitney credits her husband, John Layfield, for helping cultivate her inner renegade. For most BAM readers, John Layfield's name probably draws a blank. But among a certain demographic—namely teen and twenty-something males —Layfield is actually a much bigger celebrity than his wife.

Believe it or not, Whitney is married to one of the biggest stars of professional wrestling. Known as "Bradshaw" or "JBL" to his fans, Layfield is a WWE heavyweight champion whose in-the-ring persona is basically that of a wheeler-dealer, up-to-no-good Texas businessman who arrives at the ring in a suit and ten-gallon hat. (Think J.R. Ewing on speed). It's just an act, of course. Outside the ring, Layfield could not be any nicer—something that was actually true of all the wrestlers I met while reporting my Fortune story on Whitney.

The unlikely couple met in 2004, when Whitney was working as a financial commentator at Fox News while on a break from her analyst career. A licensed stockbroker and active investor himself, Layfield moonlights as stock market pundit on Fox's Bulls and Bears Report. Layfield was smitten—even after Whitney upbraided him on air for recommending bank stocks at a time when the Federal Reserve was hiking interest rates.

The other side of the aisle? Layfield's best man was his former tag-team partner, Ron Simmons, and his groomsmen included Mark Calaway (a.k.a. The Undertaker) and the late, great Mexican wrestler, Eddie Guerrero (motto: Cheat to Win). "The wedding photos are pretty funny," Taylor says. "But they were all great guys."

Whitney wants to have kids eventually, but for now her career is taking priority. She launched her own firm in February, and with the markets hanging on her every word, Whitney has no intention of ceding the spotlight. Unfortunately for the rest of us, she's no more optimistic about the economy today than she was a year ago.

"We're back to the 1970s," Whitney says when I ask what the next few years will bring economically.

She thinks—no surprises here—that home prices will continue to fall and unemployment will worsen. And she's dubious that the ongoing government bailouts and recapitalizations of such U.S. megabanks as Citi and Bank of America will help matters.

"It's a mistake," she says. "You end up throwing good money after bad." Whitney would much prefer to see the government put its financial heft behind smaller regional banks with cleaner balance sheets—banks more interested in growing their businesses than just saving them.

Regardless of what the government does, Whitney expects the banking world to return to a kind of It's a Wonderful Life–style lending model, where "your deposit funds my mortgage and my deposit funds your mortgage." In the long run this will make the banking system more stable, but the transition will be painful. Credit will be in short supply for everyone, as once-dominant lenders—banks that during boom times had funded their loans with borrowed money instead of deposits—are forced to shrink. "There will be millions of people who had qualified for mortgages before who will no longer qualify," Whitney says.

Asked if there's been anything about the government's response to the financial crisis that she does like, Whitney points to Congress's decision to raise the limit on FDIC insurance from $100,000 to $250,000. "Smart move," she says, noting that the higher caps have greatly reduced the risk of Great Depression–style bank runs.

When our conversation turns to her time at Brown and how it may have influenced her career, Whitney focuses in on the academic freedom allowed by the open curriculum. I quickly see where Whitney is headed with this because one of her hallmarks as an analyst—other than simply being right all the time—has been a willingness to go off on intellectual tangents that, at least at first, seem irrelevant to the valuation of a given stock.

For example, most analysts don't like to even talk about companies they don't cover, never mind write reports about them. Yet in January 2008, Whitney published a thirty-page report on Ambac, MBIA, and the other bond insurance companies that had gotten into trouble when they stopped insuring just sleepy municipal bonds and began selling insurance on mortgage-backed securities and other, much riskier types of investments.

Why did Whitney expend so much effort analyzing stocks that were not her responsibility? She knew that her banks were counting on bond insurance to limit the credit losses in their portfolios. If the bond insurers couldn't pay up—or even if they merely lost their triple-A credit ratings (ratings that extended to the securities they insured)—the banks and investment banks she did cover would be out $70 billion or more. "I guess the commonality between my time at Brown and what I do here is I pursue things that I'm fascinated by," she says.

Whitney credits her dad, the venture capitalist, for urging her to look for work on Wall Street, and it was a chance meeting with David Ebersman '91—then a Wall Street health-care analyst and today the CFO of biotech company Genentech—that convinced her to choose equity research over such other Wall Street pursuits as trading or investment banking. Asked what advice she'd have for Brown students contemplating careers in finance today, Whitney answers that, even with the recession, there are entry-level jobs to be had on the Street. The key, Whitney says, is to pursue them for the right reasons.

"Take research," she says. "It's a great job to have because you get paid to learn. You learn about fascinating businesses, and you do so at a young age. Plus, it's a true meritocracy.

"But if all you're thinking about is going to Wall Street to make a lot of money, forget it. Wall Street will no longer be a place where three or four years out of college, you can be making $400,000 a year."

In one of my final interviews with Whitney for my Fortune story, I asked her to respond to a rival analyst who had slammed her for not specifying how much lower bank stocks would have to sink before she'd recommend them. "Well," she replied, "I'd buy Wachovia at $5."

I was stunned. Wachovia had already declined from $50 to $15 dollars a share, and now Whitney was stating matter-of-factly that the fourth-largest bank in the country would have to fall another 66 percent before she'd consider the stock well priced. I hemmed and I hawed, asked if she was serious, and basically tried to save her from the hole I was certain Whitney was digging for herself. But Whitney wouldn't budge. "Five dollars," she said again.

Many months later—after Wachovia nosedived as low as $2 a share but before rival Wells Fargo acquired it for $5.87—Whitney reminded me of our conversation. "I knew you were incredulous—that you were trying to give me a hedge," she said. "But from my perspective either you make the call or you don't make it. You should have known I didn't need a hedge."

Jon Birger is a senior writer at Fortune.