In general, the Bible rewards risk takers. Consider the case of Noah, who built a giant Ark on a tip from God and, in doing so, saved the world from extinction. Or Abraham, who, after agreeing to sacrifice his son, Isaac, in order to prove his faith, was allowed to spare him at the eleventh hour. Or even the Prodigal Son, who ran away from home and wasted his inheritance money, then returned to a family who not only forgave him immediately—they threw him a lavish welcome-home party.

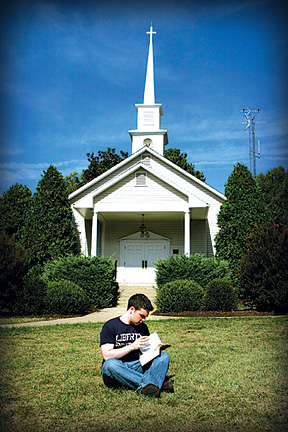

I decided to go undercover at Liberty during the fall of my sophomore year. The summer before, I had visited Liberty's Lynchburg, Virginia, campus to help my boss—A.J. Jacobs '90, editor-at-large at Esquire—research a chapter in his book The Year of Living Biblically. While waiting for him to finish an interview one day, I chatted up a group of Liberty students in the lobby of Falwell's megachurch. They told me about Liberty's top-ranked debate program, its Division I athletics, and its incredible growth rate—from 154 undergrads in 1971 to more than 10,000 resident students today, making it the largest evangelical Christian school in the world. While listening to the students talk, I was shocked —and somewhat ashamed—by how little I knew about their world and how hard it was for me, an outsider, to communicate with them. As I left the church that day, I had so many unanswered questions: What do Liberty students learn in class? Do they go on dates? Do they watch Entourage? What, exactly, does a Champion for Christ believe? And just how wide is the culture gap that separates us?

A few months later, I decided to search for answers. Thinking that a semester-long sojourn at Bible Boot Camp might make for interesting reading, I put in my transfer application and met with a Brown dean to see if I could study for a semester at Liberty and then write a book about my experiences. "I don't think a student has ever asked me that," he replied. "Actually, I'm sure no one has."

My parents, staunch liberals who worked for Ralph Nader in the 1970s, were mortified. Didn't I want to go backpacking in Europe instead? What about an internship? My roommate at Brown, a gay black activist who can quote Judith Butler chapter and verse, briefly stopped talking to me. Other friends wondered about my ability to cope with Liberty's conservative social rules, especially the one prohibiting all romantic contact beyond hand-holding. I got a lot of jokes along the lines of "A semester with no sex? And this will be different—how?"

Like any good twenty-first-century college student, I opened a new Facebook account immediately upon arriving at Liberty. I already had an account at Brown, of course, but a friend warned me that not having a profile in Liberty's Facebook network would probably raise some suspicion among my Christian classmates. (Actually, the way she put it was, "You should just carry a sign that says: I'M A JOURNALIST.") During the first few days of school, I browsed Liberty's Facebook network for hours on end, gawking at the vast differences between my friends back at Brown and the people I was meeting at Liberty. A page called "Network Statistics" described the contrast pretty clearly; among Liberty students, it said, the most-listed "Favorite Books" were the Bible, Redeeming Love by Francine Rivers, and C.S. Lewis's Mere Christianity—three solid Christian classics. At Brown, on the other hand, those spots went to Harry Potter, The Great Gatsby, and Lolita—a trio of novels about witchcraft, bootlegging, and pedophilia. (Unfortunately, the statistics confirmed more stereotypes than they broke: in the "Interests" category, Liberty's most-listed item was "God," and Brown's was "Ultimate Frisbee.")

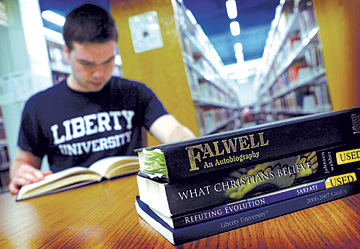

At first glance, my new world seemed to have nothing at all in common with my old one. While the traditional dating scene at Brown is famously nonexistent, many Liberty students marry before they graduate. Professors begin every class with prayer, and creation-studies tests contain questions like "True or False: Noah's Ark was large enough to carry various kinds of dinosaurs." (If you're curious, the answer is True; according to my professor, since dinosaurs and humans cohabited the earth after the Flood, they would have had to find a way to squeeze onto the Ark. He suggested they might have been teenage dinosaurs so they'd have taken up less space.) In fact, Liberty makes no bones about its distaste for schools like Brown. In one section of "Give Me Liberty," an introductory booklet given to me during orientation week, I was surprised to see, as an example of Christian education gone wrong, the name of my alma mater. The section, called "Where Visions Go to Die," begins:

As we consider [Rev. Falwell's] vision ... it is important to realize that we are not the first school to seek these lofty goals. Harvard, Yale, Princeton, and Brown were all started by churches that wanted to train students to serve Christ... However, over time the priorities of these colleges shifted, and they started to focus on increasing the perceived quality of education rather than the spiritual life of the campus. Eventually, these schools achieved their academic goals, but they did so at the expense of their original Christian purposes.... Will Liberty fall into the same trap that these universities did, abandoning our Biblical worldview in the name of contemporary academics?

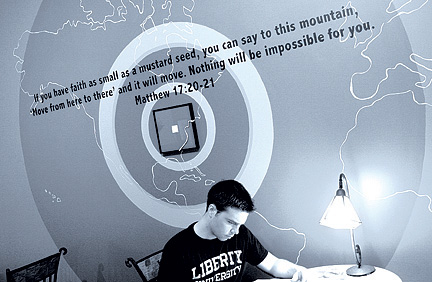

I had gone to Liberty with the intention of keeping an open mind, but I never expected my beliefs to shift under my feet. After two months or so at Liberty, though, that's what happened. I started enjoying Liberty's thrice-weekly church services. I began to sing along to the hymns. I experimented with prayer and found, to my surprise, that I liked it. I made some good friends, including a wisecracking football player from South Carolina, an evangelical feminist from Kansas, and a foul-mouthed rebel from New Jersey who wanted desperately to lose his virginity before marriage. The students who had once frightened me with their spiritual intensity were now my friends, my hall-mates, the kids I sat next to in the cafeteria, and it became impossible to write them—and their faith—off as crazy or irrelevant.

The most mind-bending moment of my semester came in late April, when I was given the chance to profile Dr. Falwell (as Liberty students call him) for Liberty's campus newspaper, in what turned out to be the last print interview of his life. Before coming to Liberty, I'd thought that Falwell was the gold standard for religiously motivated bigotry—he was, you'll remember, the guy who said on national TV after the terrorist attacks of September 11, "I really believe that the pagans, and the abortionists, and the feminists, and the gays and the lesbians who are actively trying to make that an alternative lifestyle, the ACLU, People for the American Way—all of them who have tried to secularize America—I point the finger in their face and say, 'You helped this happen.'"

And yet, meeting Falwell in person, I saw a different man than the red-faced demagogue I had loathed from afar. He spoke fondly of his grandchildren and told me about his lifelong love of practical jokes. He prayed for me and signed my Bible as a memento. He steered our conversation clear of his political controversies, and, as a result, he came across as a funny, folksy religious leader, not a hate-spewing fundamentalist. When he died two weeks after our interview, most of my friends in the secular world took it as cause for celebration. (A dozen Brown friends e-mailed me copies of an article titled "Ding Dong, Falwell's Dead.") But I mourned in earnest, remembering how kindly he had treated me.

Liberty never made me a right-wing Christian, and it never made me sympathetic to the most conservative parts of the evangelical worldview. Even while interviewing Falwell, I remember thinking that complimenting the grandfathering skills of a guy who blamed 9/11 on feminists and homosexuals was a lot like complimenting the builders of the Death Star for their metalwork: even if true, it was sort of beside the point. And throughout my semester, I never closed the gap between my two worlds.

But I did start to see that Liberty and Brown shared some unexpected similarities. Both schools produce young idealists who are both passionate about changing the world and more likely than not to act on that passion. Both foster academic life outside the classroom; on any given night in my Liberty dorm, you could find a dozen guys talking about the Reformation, hashing out complex theories of salvation, or debating the timing of Christ's Second Coming. Both schools are at their best when they cultivate real critical thinking and challenge conventional wisdom, and at their worst when they ostracize those who don't fit the mold.

And, most importantly, neither school is as homogenous as it seems from the outside. Just as Brown's reputation for left-wing hedonism fails to take into account its non-partiers, its religious groups, and its chapter of the Brown Republicans, Liberty has its share of people you wouldn't expect to find at Jerry Falwell's college: doubters, skeptics, even a few Obama supporters.

Near the end of my semester there, my friend David Leipziger '09 (who, as a gay Jewish liberal, would finish second only to my ex-roommate in a contest of stereotypical Brown students) decided, out of perverse curiosity, to come visit me. He stayed for an entire weekend, and the most amazing thing happened: he got along with everyone. Nobody knew anything about him, of course. Things wouldn't have gone so smoothly if David had come out to my Liberty friends, or if he had started a sentence, "See, at my bar mitzvah ..." But he didn't, and although he never felt entirely comfortable shielding certain elements of his identity from public view, his visit to Liberty was surprisingly pleasant. He watched movies with my roommates, accompanied me to church, and spent time getting to know my Christian friends, all without incident. I remember watching him play a game of pickup basketball with a small group of my hall-mates and being overcome by a feeling of existential warmth, a feeling that maybe the distance between Brown and Liberty wasn't as vast as I'd once thought. I realized that, in defining David and myself as the ultimate pretenders at Liberty, maybe I had forgotten that when it comes to our cultural and political associations, we're all pretenders. Real people are never as simple or unambiguous as the ideologies we choose to adopt.

After my semester at Liberty was over, I packed my bags again and prepared for my return to Brown. The next fall, my reentry shock was worse than I'd expected. Everything that had once been so familiar—professors who don't pray before class, debauched frat parties, the presence of actual, hand-holding gay couples—now seemed utterly alien to me. I lost sleep worrying that Liberty had screwed up my perspective permanently, that I'd never feel at home at Brown. Luckily, after a month or so of frantic re-acclimation, I gradually settled back into my old life. I rejoined the Jabberwocks. I picked up my Herald column where I'd left off. I even trained myself to curse again, though it still feels a little weird to let loose with a string of expletives, as if I'm auditioning for a David Mamet play.

Now, almost two years later, I still see traces of Liberty everywhere I look. When the Bible comes up in one of my classes, I'm transported back to Old Testament Survey lectures, where I learned the stories of Israel's patriarchs and got a solid foundation in quasi-obscure Biblical references. (Note to Brown students: name-dropping Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego in an English seminar will make your classmates look at you funny.) When I see a group of Brown activists protesting economic injustice in the Third World, I think of my Bible-study sessions at Liberty, where I pored over Jesus's teachings about helping "the least of these." And last November, on election night, as I celebrated the arrival of a political savior with several thousand other Brown students, my thoughts turned to a church in Lynchburg, Virginia, where I'd seen the same mass jubilation every Sunday during worship.

After meeting hundreds of evangelical students with hugely complex personalities, and finding shades of gray in a world of black and white, I find myself wincing when a friend from Brown starts railing on "crazy pro-lifers" or "stupid Bible-thumpers," just as I would politely object if a Liberty student characterized the secular left as a bunch of "tree-hugging baby-killers." To be sure, most students at both schools don't engage in such extreme caricature. But I can't help thinking that for the few who do, a little exposure to the other side might change their minds. It certainly worked for me.

A few months after leaving Liberty, I went back to tell my friends there—who still didn't know I was writing a book about them—about my true identity and my motives for coming. I expected them to be angry, but strangely, they all forgave me immediately and unconditionally. That cleared my conscience, of course, but it also reaffirmed the guiding hope of my semester: that a Brown student could get along with a Liberty student despite their differences, that friendship could trump faith, and that I could transcend my own prejudices by putting myself in the shoes of people I didn't necessarily agree with.

Now I'm left to wonder what's next. Will the American culture wars go on indefinitely? Will tree-huggers and Bible-thumpers continue to talk past one another? Or will we be able to stop ourselves, listen, and learn?

In deo speramus, indeed.

Kevin Roose's book about his Liberty experience, The Unlikely Disciple: A Sinner's Semester at America's Holiest University, will be published March 26. He plans to graduate from Brown next winter.

For more information about Kevin, go to www.kevinroose.com.

Further Reading: