In the fall of 1998, famed photographer Erich Hartmann and his wife were in Salzburg, Austria, arranging to have some of Erich's photos shown at a gallery there. The exhibition would be called Where I Was and would feature a sampling of his work from the past 50 years. No specific date had been set; the gallery committed to "sometime in the next year."

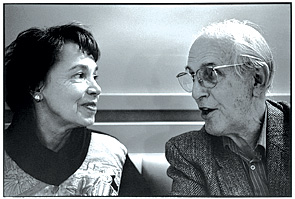

Ruth and Erich married in 1946, when his photographic career was just beginning. He started out taking portraits, then became a freelance photographer for Fortune and began composing poetic depictions of industry and technology. In 1952 he joined Magnum, a cooperative run by some of the world's most famous photographers at the time, including Robert Capa and Henri Cartier-Bresson. He also freelanced for Life, Time, and Newsweek and did corporate work as well, bringing an artistry and beauty not previously seen in annual reports and promotional brochures.

Erich had fled Nazi Germany as a teenager, and in late 1993 and early 1994, he spent two months in Europe photographing more than 20 concentration camps. Ruth joined him during January 1994 and described the trip in an essay published in the October 1995 BAM : "In the depth of winter, we went to Poland: my husband to witness, in his profession as photographer, the remains of the death camps.... I to stand in those places of terror and death, to listen to the stones—to listen to the earth."

Ruth Hartmann did eventually organize the exhibition her husband had planned in 1998. She then organized shows in Germany, Italy, and France. This summer she was in Paris for an exhibition of Erich's work at Magnum's French headquarters. It featured about 50 black-and-white photographs, all depicting the Hartmanns' home in Boothbay Harbor, Maine, and the landscape around it.

Hartmann says her ambition is to ensure that her husband's work never be forgotten. "You don't wait for things to happen if you can do them yourself," she says. "How much time do these galleries have for someone who has already died?"

Hartmann was also happy to spend several months organizing hundreds of her husband's prints that he had made during his lifetime. "I owe this to him," she says. "He died while he was still working. He had assignments for the next week."