On March 15, 1946, in the Pembroke Field House, I had my first date with the man with whom I would spend the next sixty-one years. It was not a propitious occasion.

It was in the spring of my sophomore year. The campus, after several years of domination by women during World War II, was being flooded by returning veterans. Those few male students whose college careers had not been interrupted by the war and those who were still in Navy ROTC and V-12 programs—young men whose egos had swelled while they'd enjoyed the pick of the Pembroke crop for several years—were being dropped like hot potatoes, as it were, as the heroes returned to pick up their broken lives. They were mature and grizzled-looking compared to the fresh and fuzzless faces of the students they now joined.

Pembrokers, eager to make up to the returning servicemen for those irretrieveable years, began a series of open-house parties for veterans, each one a welcome-home-and-here-we-are-to-make-you-happy occasion. In those days, I was not only shy but had little experience with boys, let alone men who were veterans of almost four years of combat. So I had no desire to attend any of these functions. I was more concerned with passing English 171 and Biology 2, not to mention the other three courses I was taking. But my friend Molly seemed desperate to meet a veteran. She wanted to attend the first open house the following Friday, and she needed a crutch: me. She knew I would be no competition for the men, but I could serve a useful purpose as someone with whom she could chat while waiting, like a spider in a web, for a veteran to cross her path. I resisted for a day and a half, but finally agreed to go.

In those days the Pembroke Field House was a meeting place for athletic social events. It was not the most romantic place to meet a man, but when we arrived the record player was jumping with the sounds of Harry James and Glen Miller, and food and drink were plentiful. I wore a straight navy wool skirt with a light-blue print blouse, and a short navy bolero. I wore silk stockings, which I'd bought with borrowed ration stamps and carefully saved for special occasions, and my shoes were my best navy pumps with one-inch heels. I was a tall girl, and very self-conscious about my height. I believed that men didn't want their dates to be taller than they were.

Molly and I entered the Field House with trepidation, giggling nervously as we kidded each other for being nervous. We passed through the main door, crossed the hall, and paused at the doorway to the party. My palms began to sweat, and I felt cold. The room was already crowded with dancing couples, as well as couples standing around in earnest conversation or munching on small sandwiches and sipping Coca Cola. Not even for veterans was beer or liquor allowed in the Pembroke Field House. Everyone was having fun; everyone seemed relaxed. How could I ever blend into that crowd of strangers and blithely engage in small talk with a man who'd been in a war?

I swallowed, though my mouth was dry, and began to back out the door. But more girls were arriving, and Molly and I were gently pushed into the room, where Molly immediately spotted a man she knew. "Thanks a lot, Shirl," she said. "I'll remember you in my will." And then she left me standing alone.

With my back against the wall, I looked desperately for an escape from the old, familiar feeling that was clutching me in a vise-like grip. I forgot that I was there to entertain, to cheerfully chat with one of the strangers in the crowded room. What could I say? What should I talk about? My mind became as paralyzed as my body, and I leaned against the wall for support, wishing I could either find someone I knew, or turn and walk out of that room. I was rooted to the spot. "Wallflower, wallflower," sang a voice in my head. A trickle of perspiration ran slowly down my back between my shoulder blades. I pressed harder against the wall to stop its progress.

Suddenly I saw the familiar face of a man from my English poetry class. And, miracle of miracles, not only was he by himself; there was an empty chair beside him. I landed on it as if my life depended on reaching it before someone else did. I took a deep breath. "Hi," was all I could manage.

The man turned toward me, smiled tentatively, and returned the greeting. He obviously didn't know who I was. "My name is Shirley," I said. "I'm in your English 171 class."

"Oh," he said. "Oh yeah. Dr. Prescott's course."

"Right," I said, "We're studying Yeats."

None of the veterans wore their uniforms. This man wore a blue pinstriped shirt with an open collar above khaki trousers and scruffy loafers. He looked like any college kid, only older.

He was still smiling, but his eyes had already begun to wander. I tried to remember something, anything, about William Butler Yeats. But the truth was, I wasn't doing very well in this course. I found not a few of the poems difficult to understand; Sara Teasdale was more my style. But I persisted, reciting all the facts I could remember about Yeats.

Because these were few, the chitchat soon ground to a halt, and rather than listen to a discourse on, say, Robert Browning or Alfred Lord Tennyson, this hapless male asked me to dance. The trouble was, my dancing wasn't that much better than my conversation. But then, neither was his, and so we shuffled together, then made our way to the punch and sandwiches. When it seemed there wasn't anything left to do, he asked if I would like to go downtown for a beer. I was stunned. But I said yes, as relieved as he was, I found out later, to leave that crowded, well-meaning, but artificial party.

We went out into the evening and began to walk down to the center of Providence. The air was soft with the promise of spring, and we walked well together, my long legs keeping stride with his. Before we had gone three blocks he began to tell me about his girlfriend at Mt. Holyoke College. He was in love with her, he said, and as if to ease any feelings of rejection this news might create, he told me what a nice kid I was, and how I should stay that way because someday I'd find the right guy. And so, before we reached the Old France, which had the cheapest beer in town, I had been rejected as a girlfriend but accepted as a friend. I found myself beginning to relax. He was as good as taken, I felt, so there was no longer any need to impress him with brilliant conversation or flirtation, neither of which I was much good at anyway.

So we just talked. We talked about our lives and about the idea of love and about our hopes for the future. We talked about our fears. Talking became easier and easier.

We shared three beers before his money ran out, and then we started back up the hill to Pembroke. Partway up the long hill I confessed that I enjoyed talking with him because I didn't have to put on an act and pretend to be someone I wasn't. As soon as I said it I felt I had made a fool of myself, and so I fell silent as we trudged through the trolley tunnel.

He delivered me to Sharpe House, where I was living that year, and left. I knew I wouldn't see him again except in English 171, but as I was putting in my last curler before going to bed, a question crossed my mind. If he was all tied up with a Mt. Holyoke coed, why had he gone to the veterans' open house party?

A couple of weeks later he called and asked me to go to a dance at his fraternity house, Delta Upsilon. Spring had arrived by then, and the air was soft. After we'd danced awhile, we walked around campus and took it in. We dated a few more times that semester, and that summer I got a job as a hotel waitress on Martha's Vineyard, where he lived.

By the end of the summer we were pretty close, and when we met again at Brown that fall, he told me he had broken up with his Mt. Holyoke girlfriend. In November, when I visited his family for Thanksgiving, he proposed. It was a very casual proposal, offered in a duck blind on the edge of Tisbury Great Pond.

Ducks were scarce that early morning, and so he turned to me and said, "You wouldn't marry me, would you?"

Without pausing to think it over, I said, "Sure."

And that was that. A few months later he got his fraternity pin back from Mt. Holyoke and gave it to me. In those days a fraternity pin was as good as an engagement ring. At last I felt as if a wedding might really happen to me.

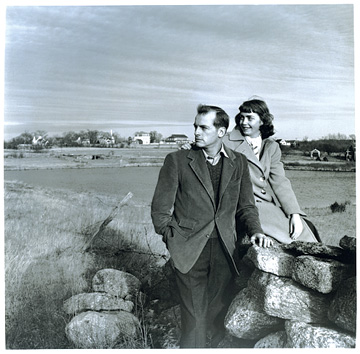

I married Johnny Mayhew '43 in September 1947, after he'd graduated. I tossed away three years of education without hesitation. For sixty-one years we have lived on the Vineyard, in West Tisbury, and raised a son, two daughters, and three granddaughters in this wonderful small town. I couldn't have had a better life.

Last June, after a long period of declining health, Johnny Mayhew entered a nursing home on Martha's Vineyard. Shirley Mayhew, who is now eighty-two, visits him almost every day. She still lives in their West Tisbury home.

All photographs courtesy Shirley Mayhew.