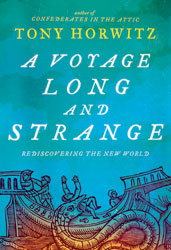

if, as the british novelist L.P. Hartley once observed, "the past is a foreign country," there are few better tour guides to this alien land than journalist-historian Tony Horwitz. In such wise yet witty works as Confederates in the Attic and Blue Latitudes, Horwitz ferried readers through time and space, revealing the ghosts from the past that continue to haunt the American South and the far-flung islands of the Pacific. In his latest work, A Voyage Long and Strange, Horwitz turns his attention to what would seem at first glance a familiar subject: colonial North America. In his hands, however, the ordinary quickly emerges as anything but. Although popular legend traces America's origins to the Mayflower's landing at Plymouth Rock in 1620, Horwitz points out that the Pilgrims were actually latecomers to the New World. For more than a century, other Europeans had trekked, traded, and plundered their way across the continent. It is this vast terrain of early encounters—the strangely little-known "foreign country" of colonial North America—that Horwitz maps with characteristic verve in A Voyage Long and Strange.

Nevertheless, Horwitz's beguiling and often conversational prose masks what is, at heart, a project of considerable intellectual sophistication. Seemingly unintentionally, over the past decade he has helped shape the booming academic field of historical memory, which has revealed the surprisingly selective nature of our understandings of the past—the protean and inevitably political ways in which societies remember (and forget) key portions of their history. (Horwitz is not immune: A Voyage Long and Strange pays far less attention to French and Dutch explorers than to their Spanish and English rivals.) But one need look no farther than the dominant place that Plymouth's Pilgrims continue to play in present-day imaginings of "America" to realize the virtues of his latest offering. If the territory Horwitz explores with such aplomb is ever to become a familiar homeland rather than a foreign country, it will be thanks in no small part to books like A Voyage Long and Strange.

Karl Jacoby is an associate professor of history at Brown.