Every war has its own vocabulary of death.Words like napalm and pacification are forever linked with the war in Vietnam. In Iraq and Afghanistan the analogous term is improvised explosive device, or, more familiarly, roadside bomb. These bombs killed so many people that it was easy to miss the news story of the death on May 7 of thirty-one-year-old Michael Bhatia '99, killed by an improvised explosive device on a remote road in eastern Afghanistan.

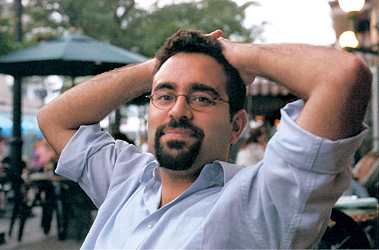

At the time of his death, Bhatia was already a distinguished scholar. A magna cum laude international relations concentrator at Brown, he was a Marshall Scholar and, while still an undergraduate, served as an intern with the U.N. High Commission for Refugees in Saharan Africa. From July 2006 to June 2007, he was a visiting fellow at the Watson Institute, where he taught a senior seminar called "The U.S. Military: Global Supremacy, Democracy, and Citizenship." Since graduating, he had also been a graduate student at Oxford, and had worked for a number of nongovernmental organizations in Kosovo, Macedonia, Montenegro, and East Timor. He was also an amateur photographer. (Some of his work is included on these pages.) When he was killed, Bhatia was working on his doctoral dissertation at Oxford: "The Mujahideen: A Study of Combatant Motives in Afghanistan, 1978–2005," for which he had interviewed 345 combatants in the country.

Such are the facts. To convey Bhatia's character, the following reminiscences were written by two people who were particularly close to him: his former teacher and colleague Jarat Chopra and his friend Sasha Polakow-Suransky '01.

The Loss of a Heart and a Mind

By Jarat Chopra

I quickly dubbed him "Bhatia," which he countered with "Chopra," a familiarity that stuck from his arrival as an undergraduate. One day I admired a picture amid the physical trappings of his cherished inspirations. Without hesitation he presented to me a framed portrait of Lawrence of Arabia gazing into one of his own quotations: "All men dream, but not equally. Those who dream by night in the dusty recesses of their minds wake in the day to find that it was vanity: but the dreamers of the day are dangerous men, for they may act their dreams with open eyes, to make it possible." Indeed, Bhatia had the makings of a most dangerous man.

Internationalist

Once in East Timor, militia that was methodically destroying the country village-by-village ignited a house before us. Automatically, Bhatia disappeared behind a bush, and before I could react I saw him next with a bucket of water dousing the flames. The exploit was captured by the press, which beamed footage around the globe before the reporters and cameramen joined villagers battling the blaze. The compassionate impulse was not without a cost: as we followed a dirt path leading away from the smoldering ashes, the militia confronted us, delivering blows that Bhatia would later dismiss as soft, pudgy slaps.

On another infamous occasion, during the retreat by the U.N. that had promised it would not, 2,000 Timorese gathered next to the headquarters compound. As employees who had helped convene a referendum, they were now targets at considerable risk. In the darkness tracer bullets were fired suddenly into their midst, whizzing streaks of light adding to the terror. In the panic, Bhatia and I knew that the bureaucratic response would be to keep local staff out. I rushed to a blue gate separating the two sides, trying to force it open while sentries in blue shirts tried to close it. A few paces away, under a high wall topped with razor wire, Bhatia caught children tossed over by their parents and disentangled those dangling in the air. The acts would be immortalized by fictional characters in the feature film Answered by Fire. Through the rest of the night, Bhatia tended to each of the families, sharing with them food and water and administering first aid.

Years later, on the eve of Timor's descent into another round of violence, Bhatia wrote to me recalling that bitter episode, linking it to the Greek concept of kairos: "a point," he explained, "where the time is right and ripe for each individual, a cataclysm of sorts, when the decisions made will shape the rest of one's life. The U.N. compound was my most immediate association."

Coming to terms with the enormity of desperate situations, we found refuge in the notion of "senseless kindness," as articulated in Life and Fate, the magnum opus of the Soviet journalist Vasily Grossman, who was horrified by the march he covered from the battle of Stalingrad to the fall of Berlin. Senseless acts of kindness toward a soul that may even have done you harm appeared to be the only means of subverting overwhelming evil. In apparently insignificant gestures incapable of altering the course of events lay the very power of a goodness that balanced the odds. Bhatia's accomplishments aside, without his senseless kindness we are now in a colder and darker place.

However long someone lives, a life is ridiculously brief. At the moment of my own father's death five years ago, I was beset by the feeling that we are here only long enough to be tested, as if in a cosmic laboratory. We cannot seem to alter the circumstances; we can only choose how we behave in them. That choice, though, somehow makes all the difference.

Participant-Scholar

At Brown, Bhatia endeavored to serve at the conceptual and actual frontiers of what might have become an internationalist order. Between the end of the Cold War and the start of another one, he was studying international relations at a historic time of grand experimentation in the business of making peace. In those "inter-war years," Bhatia actively began his dual career of publishing and of operating in the field—the field then being for him Western Sahara.

Bhatia discovered that peacekeeping and the humanitarian enterprise were concrete paradigms and vehicles for what he had the urge to do. He also recognized that a new type of career path was coming into being. Jobs which had been anomalous deviations from the norm were proliferating and increasingly accessible, and he believed the route to them should be institutionalized for his classmates. He joined a group of pioneers that founded Outposts, a student organization dedicated to direct, individual participation in the international system. Any step forward Bhatia took, he kept open the door behind him for others to follow.

In May 1999, in my capacity then as director of the Watson Institute's international relations program, I had the unique honor and special pleasure to present Bhatia with his degree and to shake his hand ceremoniously. On the stately grounds of the John Brown House, he was graduating with not only a Bachelor of Arts but a well-developed calling.

Peacekeeper

That summer his baptism under fire was nothing less than the fall of Dili and a conflagration throughout East Timor. It would be a painful hour of trial for us both. He was mostly fearless, but in flashes of fear Bhatia proved truly courageous, and this impressed me, however well I knew him. I find that only a few people act with benevolence under any set of conditions, just as only a few act always with malevolence; for the majority the distinction depends on how much pressure one is under. Bhatia's sincerity under the gun put seasoned veterans to shame. Some attributes are not a matter of experience but of fundamental stuff.

What began as an exercise in election observation—standard enough—ended in the Caesarian birth of a nation. Bhatia experienced for the first time in a conflict zone the human dimension of gross suffering, the desperate powerlessness and wrenching dilemmas, the arresting abruptness of being shot at, the gradual death of a bullet-ridden man resisting resuscitation, the sound of singing in churches by people encircled and trapped, the yearning for a moral high ground while bearing witness to the perpetrator, and the insoluble puzzles about the human condition and one's place in it. Alone in an empty convent, winded after a night spent surrounded by perpetual gunfire, we murmured the title of a book by the Polish war-correspondent Ryszard Kapuscinski: Another Day of Life.

A general evacuation from a town whose smoking inferno was photographed from outer space enabled us to reach Bali, the headquarters of the Indonesian military units then implementing a "scorched-earth" policy. We walked in past the guards, demanding an accounting of what happened to a couple of thousand children we had been forced to leave behind at the Red Cross compound. Typically, Bhatia, seeing the safe haven getting waterlogged from leaking pipes, had begun to shovel dirt and move stones. Small three- and five-year-olds began doing the same, trundling behind him, trying to dry the soggy enclosure. The next dawn they would go missing. Passing through hallways we sought the demon responsible. There in a small room we found him: a duty officer who was in fact Timorese, himself in tears because for days he had not heard from his mother or sister.

While he was in Afghanistan, the post–9/11 setting changed the logic of peacekeeping. Chronically, state-building interventions blundered obliviously into the deep-rooted social and political dynamics of indigenous communities. Coalitions in Afghanistan and Iraq repeated the U.N. mistakes in East Timor. To improve its knowledge of the grassroots landscape, the Pentagon deployed social scientists, including Bhatia, as part of a "Human Terrain System." Thus the tools of an impartial third party were absorbed by combatants fighting an enemy, and adapted in counterinsurgency and stabilization operations. The new context was highly complex, but Bhatia had the best chance of navigating through it at the remotest edge of the front lines.

Being unable at times to change the world does not mean the world needs to change who you are. I saw Bhatia at the limits of endurance, and he was the personification of a humanitarian and the antithesis of the many unscrupulous officials and fraudulent charlatans who pursue self-advancement under the cover of humanitarianism. Bhatia never succumbed to the relentless mores of an anonymous kind of "professionalism" that sacrifices human relations and personal loyalty. Nor was he crushed by the forces of pessimism that render good intentions into camouflage for ulterior motives. He matured and evolved and adapted down crisscrossing paths of his loves and wars, but he remained true to himself.

I will never forget the words of his mother when she broke the news to me:

"He wanted to do what he did."

Jarat Chopra was a Brown faculty member from 1990 to 2007. He recently helped develop the U.N. strategy in Somalia.

The Fearless One

By Sasha Polakow-Suransky '01

We sensed our way, running or biking, through the dense pre-dawn fog along the empty cobbled streets of a sleeping city. Bhatia led the newcomers among us into Christ Church meadow, teaching us to scale the eight-foot iron gate—still locked at that hour—in the dark.

In addition to his intimidating intellect, impressive resume and worldwide network of friends, students, and admirers, Bhatia possessed a passion for rowing. Lacking the tall, hulking physique of many rowers, he never made the Brown crew team. But at Oxford, where anyone with arms is encouraged to row, he took up crew and recruited others like an evangelist, including scrawny novices like me. One morning when the coxswain overslept, Bhatia decided to cox the boat himself, cramming his substantial frame into the narrow seat usually occupied by someone weighing barely 100 pounds.

I first met Michael Bhatia at Brown in late 1999. He had just returned from East Timor after having witnessed the violent aftermath of its referendum for independence from Indonesia. His reputation preceded him. Anyone concentrating in international relations or taking classes in the department had heard his name. And by the time of his graduation, Bhatia was something of a legend. Rumor had it that he had returned from Dili with hundreds of images depicting the Timorese voting for independence in the face of violent state repression. It was not every day that a recent Brown graduate returned from a war zone with original material, and I encouraged Bhatia to write something for the College Hill Independent, which I was editing. He regaled me with stories for hours on the phone and eventually wrote a powerful firsthand account of the events he witnessed. He was far too self-effacing to mention his small acts of heroism.

For Brown students who sought to follow in his footsteps and study in England, Bhatia was obsessively supportive. He would read draft after draft of application essays, offer his assistance to the dean's office during fellowship selection, and host visitors in Oxford, fetching us from the bus station in the pouring rain and leading us, down a winding alley, to one of his favorite pubs, the Turf Tavern.

He was intellectually fearless. He loved a good debate, but was impatient with people who regurgitated the received wisdom of the day or who clung to ideological mantras. He forced his friends, his students, and his antagonists to examine their most deeply held beliefs, and he never shied away from controversy.

In early 2002, Bhatia traveled to Israel with a group of Rhodes and Marshall scholars as part of Project Interchange, an all-expenses-paid trip for opinion leaders organized by the American Jewish Committee (AJC). He regarded the spectrum of Israeli and Palestinian views the AJC presented as far too narrow, so after the official trip ended, he arranged a separate one to the West Bank and Gaza so he could speak with ordinary Palestinians and the Israeli soldiers serving in the occupied territories. He returned with stories of Palestinian ambulances held up at checkpoints and of bored Israeli soldiers who complained they were serving in dangerous areas to protect only a few hundred settlers. Bhatia took the AJC to task in the journal Middle East Policy, criticizing the trip for reinforcing Israel's founding narrative without allowing participants to see the settlements and occupied Palestinian areas that lay at the heart of the conflict, a form of selective exposure that he believed misled visitors and perpetuated the conflict without offering any constructive solutions.

The criticism didn't faze Bhatia. He was an Ivy-Oxbridge academic with deep expertise on the political motives of combatants in Afghanistan. He had published scathing critiques of the U.S. and NATO conduct of the war in Afghanistan. He knew far more about the politics of post–9/11 Afghanistan than all but a handful of other specialists, few of whom were willing to put their lives on the line there. Bhatia refused to be an armchair critic, or to confine himself to the ivory tower. He offered his expertise to the Army's 82nd Airborne Division. He chose to focus on the Human Terrain program's possibilities instead of on its failings. He joined up believing that it would help reduce casualties among both Afghan civilians and NATO soldiers.

And so he was killed on the way to mediate an intertribal dispute near the city of Khost. The soldiers and academics who served with him joked that the Afghan Human Terrain program should be renamed Bhatia Mediation Services because of his success in negotiating solutions with local tribal elders. His friends spoke—with no illusions—of his one day becoming U.S. Secretary of State or U.S. ambassador to the United Nations. When faced with such speculation, Bhatia simply rolled his eyes.

Our country has lost one of the most promising diplomats of its youngest generation of leaders, and Brown has lost one of the most formidable and unconventional minds ever to emerge from the Van Wickle Gates. And the hundreds, if not thousands, of people whose lives he touched have lost a dear friend.

Sasha Polakow-Suransky is associate editor of Foreign Affairs. He studied at Oxford with Michael Bhatia from 2003 to 2005.