What do you call the literature that comes from forty-six countries with more than 2,000 languages and 3,000 ethnic groups? Right now we call it African literature, lumping together all the continent's writers into the same genre. According to a panel of African authors who gathered at Brown in April, the term does a profound injustice to the diversity and complexity of their continent's literature. Novelist Nadine Gordimer, a white South African woman of Jewish descent, gets thrown together with Chinua Achebe, a Nigerian man of Igbo tribe descent. And what about expatriot African writers living in Europe writing about their home country for a western audience? How do you identify them?

Photos by Frank Mullin

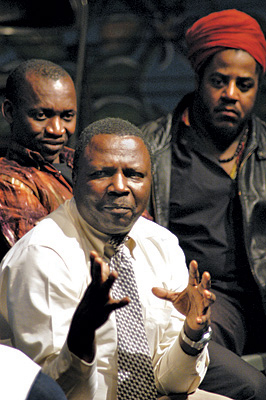

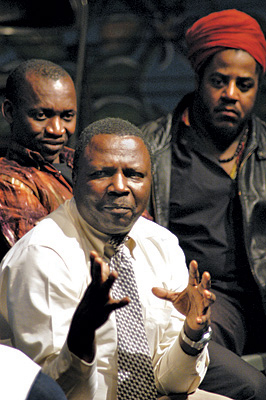

Donald King '93 (right) moderates a discussion with playwrights Charles Mulekwa (left) and Pierre Mujomba.

Jack Mapanje, a Malawian poet and linguist, argued that the best way to categorize African writers is by generation. The first generation, he said, wrote when the missionaries came in the 1800s. These writings, he said, were not critical of the evangelizing Westerners because the missionaries themselves were publishing their books. The second generation includes such writers as Achebe and the Nobel Prize–winning Nigerian writer Wole Soyinka. They wrote about nationalism, Mapanje said, and the struggle for independence from colonial powers. And the latest generation, he said, has found inspiration in Africa's tradition of oral storytelling, reconceiving those fables for modern times.

Chenjerai Hove, a Zimbabwean novelist who is now a fellow at Brown's International Writers Project, said if there was one common characteristic among African writers it was—or should be—their subject matter. "We have to name the new power," said Hove, referring to the post-colonial dictators and strongmen who rule many African nations. Hove knows firsthand about the abuse of power. A human rights advocate and critic of Zimbabwe's President Robert Mugabe, Hove fled to Europe in 2001 after he and his family were placed under constant surveillance by the police and had their lives threatened. "How does power work and in whose hands?" he asked. "Power has victims and victimizers." In a literary way, how do we handle these new experiences?"

Actors read excerpts from the plays at the Rites and Reason Theatre.

Somalian writer Nuruddin Farah, one of Africa's most most prestigious novelists, made the most radical and global argument. He said birthplace, language, and ethnicity should never be used to categorize a writer. "In the world I belong to, there is one huge narrative and that narrative began thousands of years ago," he said. All that matters, he said, is a writer's contribution to that narrative—what he says about universal themes like father-son conflicts, for example, or how he enlarges our understanding of human nature. "There is nothing that can be referred to as 'African literarature,'" Farah said, "unless what we mean to do by using the term is to justify commercialism, book sales, employment opportunities for professors, or writers selling their books."

The seminar was part of "Under the Tongue: A Festival of African Literature" and sponsored by the International Writers Project.