There was a time in the late 1960s when almost everyone wanted a bulova watch. Lyndon Johnson declared the high-end model, the Accutron, to be the White House’s official Gift of State, but you didn’t have to be a head of state to buy Bulova’s Caravelle, a bejeweled watch that sold for under thirty dollars. NASA adopted much of Bulova’s breakthrough technology in its space program, and in 1969 several Bulovas were taken along by Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin on their historic Apollo trip to the moon.

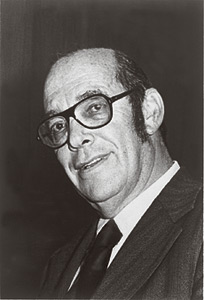

The man behind Bulova’s success was Harry Bulova Henshel, the grandson of the company’s founder, Joseph Bulova. Henshel died of kidney and heart disease in June at his home in Scarsdale, New York. He was 88.

The man behind Bulova’s success was Harry Bulova Henshel, the grandson of the company’s founder, Joseph Bulova. Henshel died of kidney and heart disease in June at his home in Scarsdale, New York. He was 88.

Henshel began overhauling the Bulova line shortly after becoming head of the watch empire in 1959. The company was known for its luxury watches, but the success of Timex convinced Henshel to target budget models as well. Over the next decade Bulova’s profits went from $2.5 million to roughly $6 million. Along with Timex, it dominated two-thirds of the U.S. watch market.

The product Henshel may be most remembered for is the Accutron. Introduced in 1960, it revolutionized watch design as the first-ever electronic watch. Instead of springs or a balance wheel, the watch contained a tuning fork driven by a battery-powered transistor circuit. For the first time ever, a watch hummed rather than ticked. The Accutron emerged as the most accurate timepiece of its era; the company guaranteed it would never be off by more than two seconds.

Henshel may have driven the technological watch revolution of the sixties, but by 1970 he found himself struggling to keep up with the rest of the industry. In 1972 the Hamilton Watch Co. introduced the Pulsar, the first watch with a digital display and a space-age look. “He thought it was a fad,” Henshel’s wife, Joy, said in an interview shortly after his death. Then, when Japanese quartz watches hit the market, their greater accuracy displaced the Accutron.

Bulova introduced its digital watch in 1975, but by then the company was losing $21 million a year and its market share had dropped to only 8 percent. In 1979 the Loews Corporation bought Bulova and within four years had restored it to profitability. Although Henshel maintained an office at Bulova’s headquarters in Woodside, New York, he no longer controlled the company.

Henshel was an avid horse racing fan and bred his own horses. He was a benefactor of UNICEF and the White Plains Hospital Center and served on the boards of the Parsons School of Design and the New School in New York City.

In 1945, the Bulova family set up the Joseph Bulova School of Watchmaking to teach disabled World War II veterans the craft of watch repair. Henshel supported and promoted the school until the introduction of digital watches, which did not require trained jewelers. The school closed in 2000.

He is survived by his wife, Joy, four daughters, and four grandchildren.