Days of Wine and Labor

In 1998 William Denny bought his dream house, a 1768 farmhouse complete with a walk-in fieldstone-lined fireplace and original wide-plank floorboards. The house needed few repairs, and the location was ideal—Chester Springs, Pennsylvania, about an hour west of Philadelphia and only a few miles away from where Denny and his wife, Gay, had earlier lived.

The garden, however, was a different story: more than fifteen acres of overgrown weeds, fallen branches, desiccated saplings, and out-of-control grapevines. Denny, a self-employed money manager, had virtually no experience as a gardener. At his previous home, he’d had what he calls a “victory garden”—he was satisfied if it yielded a few tomatoes a year.

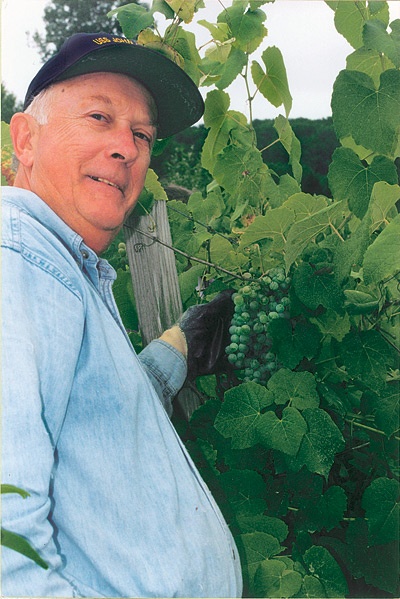

But the grapevines caught his eye, and his imagination. Nearly ten years later, Clover Mill Farm Vineyards and Winery is thriving. Its wines, which include both reds and whites, can only be bought at the vineyard itself, but Denny says he makes a profit of several thousand dollars every year by selling directly to customers. But the real benefit, he says, has been “taking on a project that involved quite a bit of effort and making it work. That’s brought a lot of satisfaction.”

The first step was clearing away the underbrush. It had grown up in two years, but it took three to get rid of it. Denny and his wife worked four hours a day, five days a week hauling away branches and weeds and liberating the grapevines that lay buried beneath. There was no one to guide them. Denny read some books on wine making, and followed instructions. He learned from his mistakes. “It was,” he says, “a lot of work.”

With the garden cleared, Denny and his spouse salvaged whatever grapevines they could and planted others, using chardonnay and cabernet root stock from France that had been cultivated to withstand harsh winters like those in Pennsylvania. The vineyard opened in 2001, and now Denny’s two-and-a-half miles of grapevines produce about a thousand cases of wine a year. He says he’s developed his own unique wine-making process that halts fermentation slightly early, leaving behind more grape sugar than usual and creating a semisweet taste rather than one that’s fully dry.

This September, Denny was once again, in his words, “knee-deep in the harvest.” He has converted an old carriage house into a facility where the grapes are crushed, fermented, and then stored in fifty-nine-gallon oak barrels. He and his family do all this themselves.

Denny’s house also has a deck. On warm days, he sits out there in a rocker sipping one of his wines and looking out on the vineyard that his own hands built.