The Diva of Cool

In May 2004 Lauren Zalaznick faced the kind of good-news/bad-news scenario that keeps TV executives awake at night. She'd just been hired to run Bravo, the cable channel that first became widely known for the sardonic hit reality series Queer Eye for the Straight Guy. Now her bosses wanted to know what she could do to sustain, and perhaps surpass, the success of that earlier hit. How, they asked, would she parlay a single hit show into an entire slate of must-see programming?

Zalaznick got to work. She broke down Queer Eye’s appeal into what she called five “content affinity areas” that would define the station’s future programming. That fall, she launched Project Runway, a reality show about a group of unknown fashion designers forced to create outfits with limited time and money. Zalaznick believed the same audiences that loved Queer Eye’s witty tastemakers would be galvanized by a behind-the-scenes look at high-strung fashionistas.

The early ratings suggested otherwise.

“For the first three episodes, the show tanked,” recalls Runway cohost Tim Gunn, who says he was about to visit the final contestants when the news came through. “The ratings were so bad we might not even run the full season.” Zalaznick wasn’t fazed. Ignoring both the ratings and the skeptics, Gunn says, she kept rerunning the show through the Christmas holidays. “When the fourth episode finally aired,” he says, “ratings were up 400 percent, and they kept going up for every successive show. By the finale, we were breaking records. Instead of pulling the plug, Lauren gave people more Runway than they probably wanted to see. That might seem counterintuitive, but it worked.”

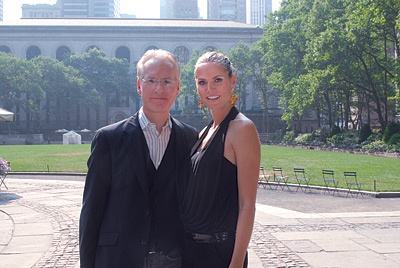

Saturating Bravo’s schedule with repeats of a show nobody seemed to like typifies Zalaznick’s against-the-grain mental- ity. For a late-afternoon lunch on the patio of Los Angeles’s Sunset Tower Hotel this fall, the rail-thin Zalaznick showed up in white jeans, a striped shirt, and running shoes. “I always want to know what the rules are,” she said about her approach to television programming. “I don’t necessarily want to break them, but I don’t necessarily want to not break them either. I just want to do what I want to do.”

Headstrong? Maybe. But by following her instincts, Zalaznick has broadened the network’s following. For seven consecutive quarters, Bravo Media has increased viewership by a total of 31 percent in the eighteen-to-forty-eight-year-old demographic. This September the network’s Kathy Griffin: My Life on the D-List won the Emmy for Outstanding Reality Program. Project Runway was nominated in three reality program categories, and Top Chef was nominated in two.

Creating buzz in the increasingly outrageous reality-TV landscape is no small feat, and Zalaznick has managed to do it by re-positioning a cable channel that just a few years ago was best known for the genteel Inside the Actors Studio. “I’ve branded the channel on an aesthetic basis, and I’ve done it on the business side,” she says. “We have a very clear formula—fashion, food, beauty, design, and pop culture. And it all feeds into this sort of aesthetic rigor of what Bravo has come to stand for.”

How exactly does Zalaznick sniff out shows destined to become water-cooler sensations? “I have a natural tendency to be curious and really cynical,” she says. “I tend to function best by not pretending to chase things that are supposed to be the next big thing. I also have an amazing development team.”

“Bravo’s upscale, educated, and arts-savvy target audience keeps tuning in,” Zalaznick says, because the network’s real-life characters include some very sharp personalities. “They’re aggressive,” she says. “They want more out of life. Most of all, they want to have fun, and we want our viewers to have fun.”

Some Bravo programs focus on celebrities like Paula Abdul (Hey Paula), but Zalaznick and her colleagues are masters at mining high drama and low comedy from seemingly mundane subjects. As packaged by Zalaznick, the daily headaches faced by Beverly Hills hairdresser Jonathan Antin (Blow Out), fitness instructor Jackie Warner (Work Out), and obsessive-compulsive L.A. rehabber Jeff Lewis (Flipping Out) suddenly become fascinating.

“My whole job, my mission in life,” she says, “is to involve audiences in people, in jobs, in stories that by all rights you would not think they’d choose to be that deeply involved in.”

Lauren Zalaznick grew up in Great Neck, Long Island, the youngest of three children. Her mother is an interior decorator; her father, a former garment-industry executive, now works in financial services. Always the smartest kid in class, Zalaznick skipped third grade and arrived at Brown at seventeen ready to hit the books. She had her own ideas about what mattered. “I did not go to Campus Dance” she says of her Commencement weekend. “That was one of my worst nights ever at Brown. I was not a joiner in that way.”

Steering clear of extracurricular activities, Zalaznick concentrated on premed courses. Until, that is, courses she took with modern culture and media professors Michael Silverman and Mary Ann Doane hooked her on movies. “Semiotics,” Zalaznick says, “afforded me the ability to read the world very critically and break down each parcel of what makes your visual world tick.”

During her senior year, Zalaznick decided to postpone school so she could explore her new passion for film. The summer after graduating—magna cum laude in semiotics—she caught a break when novelist Susan Isaacs, a Great Neck neighbor, put her in touch with director Frank Perry as he readied the film adaptation of Isaacs’s best-seller, Compromising Positions. Just a few months out of college, Zalaznick found herself employed as a director’s assistant on set with Susan Sarandon, Joe Mantegna, and Joan Allen.

After spending a couple of years observing the day-to-day machinery of Hollywood-style movie making, Zalaznick grew impatient with the hierarchies of the studio system. “When I was twenty-two I said to myself, ‘Do I really want to work in the locations department, then apply to get in the union, be a second assistant director, and then, ten years later, become the first assistant director? What do I want to do?’ And the answer was, ‘I want to be the boss.’”

So Zalaznick next teamed up with independent-film producer Christine Vachon ’83, serving as executive producer on Swoon, associate producer on Poison, and producer on Safe (the latter two directed by Todd Haynes ’85, whose newest film is featured here ).

Vachon recalls those heady times: “It was a rush to be running the show. Neither of us had ever done anything like this, and because of that, we weren’t intimidated. Lauren is organized, she’s precise, and she understands why one thing may be cheaper but another thing might make the movie better. We became comrades-in-arms. If I hadn’t had Lauren by my side I don’t think we’d have made Safe.”

Zalaznick’s shoestring-budgeted indie projects, which also included the 1996 film Girls Town and the controversial 1995 teen-sex film Kids, served as grueling but instructive cram courses in the art and science of getting things done. “Every movie is a start-up,” she says. “There are no lawyers, no accountant, no insurance policy waiting around. The entire infrastructure gets built at a very rapid pace, so I learned how to physically run a business where I’d be the boss of no people on one day and 210 people the next.”

Of course, in the world of movies, directors, not producers, call the creative shots. “Our partnership around Todd’s movies and Larry Clark’s film Kids was all about how to support a singular vision, which you have to fight for against all odds. If you have a crew going into overtime, whether or not you think [the director’s] got the shot in the can already and doesn’t need to do it again, you still have to do what your client, the director, wants.” By contrast, she says, “Producers in television have a much stronger hand in how the product actually comes out.”

By 1996 Zalaznick was ready for a change. The cable music network VH1 hired her to “rebrand” its operation, and within two years she had moved from promotions programming. Jeff Gaspin, her boss, and now president of NBC Universal Cable and Digital Content, recalls: “Lauren and I had a rocky start.

When we met, Lauren had this niche sensibility, and I have a very mass-appeal sensibility.” Zalaznick leaped into the television mainstream by producing such programs as Pop-Up Video, which pioneered the use of “info-nuggets,” bits of trivia that appear on the screen while a music video plays. She also produced Divas, about female music stars, and the VH1 Fashion Awards. “I like to think I taught Lauren to be commercial or more middle-of-the-road,” Gaspin says, “and she helped me become more open-minded. Lauren is as artsy as any one I know, but she also has great business acumen and she’s able to think strategically.”

Among those who took notice of Zalaznick’s VH1 triumphs were executives at Universal Television. In 2002, shortly after she gave birth to her third child, Zalaznick was hired as president of the company’s new TRIO Network. Despite the Peabody Award–winning documentary The N Word, and Brilliant But Cancelled, which was devoted to short-lived prime-time shows, TRIO failed to gain traction with cable outlets and folded, resurfacing later as the Internet service gettrio.com.

Thanks to her experience at TRIO, however, Zalaznick arrived at Bravo in 2004 well prepared to give the network a top-to-bottom makeover. “Lauren was very focused on creat- ing an overall look and style for the network,” says Frances Berwick, Bravo’s executive vice president for programming and production, “and quickly came up with the blueprint for what you see now”: a network where viewers are invited to “watch what happens.”

Among the talent Zalaznick brought to Bravo was Fenton Bailey, cofounder of World of Wonder Productions. Bailey’s hilariously offbeat series, Showdog Moms and Dads, was one of Zalaznick’s early programming successes, and he now produces the network’s Million Dollar Listing, which focuses on manic L.A. real estate agents. Bailey sees Zalaznick as a consummate “cool hunter” who starts pop culture trends by being impervious to them.

“The thing about cool hunting,” he says, “is that you’re not ever going to go with the herd. You have to be guided by your own radar. It’s like shopping. You have to have a great eye. Lauren has a sixth sense for what’s coming up before it happens, and she has a healthy contempt for all institutions. That actually ends up being an incredible creative boon for the institutions she works for.”

Zalaznick lives in Manhattan with her husband, Phelim Dolan ’85, a TV-commercial director who is now a day trader. The two met at Brown, and they now have a five-year-old son and two daughters, who are ten and twelve. Asked if the kids ever inspire her programming ideas, Zalaznick says no. “If I worked at Cartoon Network, maybe, but kids suck different things out of the ether. They use media differently than when I was their age, but it is my personal responsibility to not say no to the cultural things emerging around me.”

Zalaznick also chairs the NBC Universal Green Council, and her latest interest is in non-cable Bravo technologies. Last May she took over Bravo-branded publishing, merchandising, and wireless enterprises, as well as radio. Gaspin expects Zalaznick to seize the initiative in these emerging technologies. “The business is changing so much,” he says, “that you need people who don’t think like traditional media executives. Lauren is a thought leader at our company who really embraces the digital world.”

A longtime Internet champion, Zalaznick beefed up Bravo’s online presence.

She added live chats, bloggers, and such broadband initiatives as the gay online site outzoneTV.com, the snarky blogger site TelevisionWithoutPity.com, and message boards where fans can discuss Bravo programs.

“TV is going to remain at our core,” she says about Bravo, “but a very closely associated extension of that robust growth is the digital properties, whether it’s text-driven blogs or video-driven online, or whatever. Digital and cellular technological innovation drives a hell of a lot of new business, so getting into broadband and the wireless space is really exciting for us.

The job remains daunting. Even hit series have a limited shelf life, and their replacements require a lengthy lead time. Zalaznick is competing not only with other networks, but with tiny internet companies that can turn on a dime. Sites like YouTube produce no content, but simply provide a place for viewers to post. As Zalaznick said during a Commencement forum at Brown last May, “The challenge for us is that the third-largest dating site in the world is one guy in his apartment in Vancouver.” Zalaznick’s major challenge is the same one faced by so many mainstream-media executives: to transform a company rooted in old media into a significant brand amid the cacophony of user-generated content.

In the meantime, Project Runway host Tim Gunn harbors his own anxieties. “My biggest fear is that Lauren’s going to go off and run NBC Universal,” he laughs. “She has such clarity of vision. She’s deft at slicing through a ton of distractions so she can get to the core of what needs to be nurtured. If something resonates for Lauren, she makes it happen.”

Contributing Editor Hugh Hart writes about the entertainment industry for the BAM.