Rose was the first beneficiary of the Environmentally Compromised Home Opportunity Loan program (ECHO), a state program that lends up to $25,000 at relatively low interest rates to residents of areas affected by toxic chemicals.

ECHO was the brainchild of Professor of Sociology and Environmental Studies Phil Brown and two of his undergraduate students, who also ushered it through the state legislature.

It all began five years ago, when a municipal crew digging a sewer line in a Tiverton neighborhood unearthed eerily blue soil, a telltale sign of industrial contamination. Testing revealed that the soil under the neighborhood’s 130 homes contains up to thirty-seven times the acceptable limits of such poisons as lead, arsenic, and cyanide.

After the contamination was discovered, the value of residents’ homes plummeted from over $100,000 to worthless. Residents in this working-class neighborhood lost access to their financial safety net, the equity in their homes.

“Our home is eighteen years old, and a few years ago it needed a new roof, a $15,000 job,” recalls Gail Corvello, a longtime resident. “We couldn’t get a home equity loan.” Because of the contamination, she says, “the appraiser could not come up with a value for our property.”

Corvello drew from her retirement account to pay for her new roof—at a substantial penalty. But, she says, “that got me to thinking about the other people in the neighborhood. What happens if someone’s boiler lets go? Boilers cost thousands of dollars. What happens if there’s a senior citizen in the neighborhood who needs their retirement account to live on?”

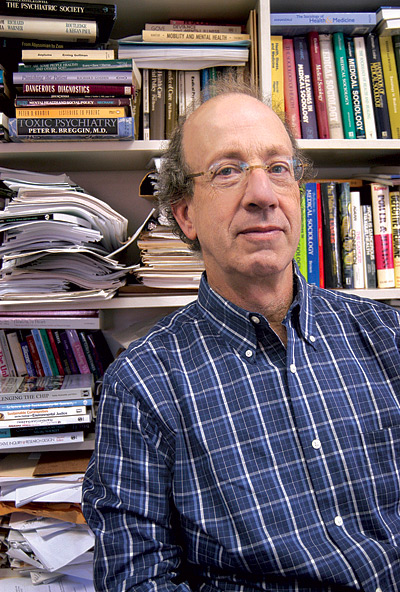

Enter Phil Brown. As director of the Community Outreach Core of the University’s four-year, $11.5 million federal Superfund Basic Research Program, he keeps in close contact with community organizations in areas affected by environmental contamination. He and his colleagues teamed up early on with the Environmental Neighborhood Awareness Committee of Tiverton (ENACT), whose president is Corvello, and off ered help with science, advocacy, and grant writing, as well as how to deal with media and government.

Meanwhile, Brown gave students in his course “The Science and Political Economy of Environmental Health and Social Justice” a chance to help out these community groups instead of writing a term paper. When Ben Hudson ’07 took Brown’s class in the spring of 2006, for example, he chose to help Tiverton residents get help from the state legislature. Hudson, who had spent the previous summer in Washington, D.C., as an intern for U.S. Senator Patty Murray of Washington state, teamed up with Sarah Fort ’06 to produce a report detailing six legislative or administrative solutions to the housing loan problems created by the contamination.

They presented the report to Tiverton’s state representative Walter Felag and state senator Joseph Amaral. After consulting with legislative fiscal-policy analysts, students and legislators zeroed in on the most promising solution: a low-income loan program.

Legislation authorizing the ECHO program was introduced into the Rhode Island House and Senate in June 2006, and signed into law on Gail Corvello’s lawn one month later. The bill authorizes Rhode Island Housing, a semigovernmental aff ordable-housing loan agency for low- income Rhode Islanders, to write loans for homeowners aff ected by newly discovered toxic-chemical dangers. The language is written generally enough to allow other Rhode Island communities to take advantage of the program. More than 5,000 people in Rhode Island are believed to be living within a mile of U.S. Environmental Protection Agency–designated hazardous waste sites.

“This is the fi rst time in the country this type of legislation has been passed,” Phil Brown says. “We’ve been working with other states who want to copy the program.” He now hopes to amend the legislation to raise the loan cap above $25,000, and to include a mortgage refi nancing option. This year, a new crop of Brown students is available to help.

“The Brown students have been tremendous,” says Tiverton’s Gary Rose. “We ask for something, and next thing we know, there’s fi ve or six of them showing up at Gail’s house, asking, ‘How can we help?’ ”