The morning dawned foggy over Vermont.

Kay Wilson Henry ‘67, just back from a three-week canoeing trip in the canyons of the American Southwest, pulled up with a Mad River canoe strapped upside down to the roof of her Audi. Her blonde hair fell to her ears in a tousled center part, and she wore sunglasses, sandals, and lightweight khaki pants. A spunky woman who seems at least a decade younger than her sixty years, Henry has a chatty, easy way about her. Her stories and demeanor seem to convey that every day is an adventure—today perhaps more so for me than for her. I’d never been canoeing before and didn’t know what to expect. We headed north from Burlington on Interstate 89 toward Swanton, where the Missisquoi River meets Lake Champlain and where great blue herons build their summer homes high in the treetops.

By the time we untethered Henry’s canoe and plunked it into the river with a splash, the sun was shining, the day was warm, and the sky was blue and clear. Henry showed me how to paddle—“Short, choppy little strokes,” she said. “Ka-chunk, ka-chunk”—and we were off. The water was a calm blue-gray, and the paddling motion felt natural and easy. The canoe was lighter than it looked. “This is a seventeen-footer, and it’s good for ease of paddling,” Henry explained. “And that’s really what Mads are known for, being stable yet easy to paddle.” She should know. She and her first husband, Jim Henry, founded Mad River Canoe in 1970. Henry ran the company continuously until 1998, when she retired from the business and turned her attention to the river.

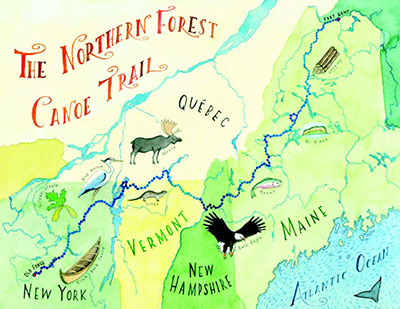

Since then, Henry has been working to create and maintain part of the Northern Forest Canoe Trail, a 740-mile water trail that connects Maine, Vermont, New Hampshire, Quebec, and New York state—including this stretch of the Missisquoi—by using historic Native American trading and transport routes. Henry and her second husband, Rob Center, adopted the Trail project and have transformed it from what it had been—scribbled pages of research in the imaginations of a handful of paddlers—to a 700-member nonprofit organization with two paid staff members and a $250,000 budget, all aimed at creating a contiguously mapped waterway complete with campsites, portage routes, trail signs, and access points.

Today was the start of the second season since the Trail had officially opened. Already two Bates College students were completing the Trail’s fourth-ever through-paddle: beginning in New York, they were canoeing their way to the end of the trail in Maine, blogging as they went. (This week’s entry: “Sun! Downstream! Maine!”) Part of the beauty of the trail is that it runs through so many different water bodies and landscapes. The routes range from slow-moving rivers like the Missisquoi, to wide-open lakes, to class IV rapids. The Trail also connects communities to one another, allowing paddlers to assemble a patchwork trip, sleeping out with a tent and a campfire one night, staying in a bed-and-breakfast the next. Some towns along the route, like Saranac Lake in New York’s Adirondack Region, are established tourist destinations; outfitters there are practiced at renting canoes and kayaks to visitors, trucking them to their put-in point and picking them up days later at a predetermined spot, sunned and sore and ready for home. Other towns have long been cut off from the tourist economy—their livelihoods departed with the timber companies—and the Trail provides an opportunity to re-invent themselves as destinations for paddlers. “For many years, the river was a sewer,” says Henry. “You didn’t even paint the buildings on the river side because no one saw it. It’s kind of fun to have these communities look at the river as a resource again.”

Henry’s passion for canoes and rivers began shortly after her graduation from Brown. Armed with a degree in geology, she worked at an oceanography lab on the Hudson River for three years before she and her then-husband, Jim, concluded that they “were really not New York people.” They found new jobs at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute on Cape Cod, but before beginning work there they loaded up a Volkswagen bus and headed west for a six-month road trip. Although camping was relatively new to her, “we basically lived outdoors” during that trip, says Henry. “I thought, ‘This is fun. I’d like to do more of this.’ ” Strapped to the top of the VW bus was a canoe that Jim had designed. He’d taken a book from the library about native North American bark-and-skin boats and, for fun, had built a mold out of plaster, then had it cast in fiberglass.

When the couple returned east from their trip, they learned that their jobs had fallen through. With nothing better to do, Jim took his boat and raced it in the national championship, held that year on the Dead River in Maine, and won. Word got out about Jim’s winning canoe, and people started asking him to build a similar canoe for them. The Henrys moved into their ski house in Waitsfield, Vermont, and Jim started building boats in the garage. Henry, always a numbers person, took over the business end of the fledgling company while her husband continued to design canoes. Soon, Mad River Canoe had a building in downtown Waitsfield, more than eighty employees, and 200 dealers selling a line of more than twenty canoes—“Everything from little twelve-foot solo canoes to big eighteen-and-a-half-foot racing boats,” Henry says. The company had also made a name for itself as a manufacturer of quality high-end boats and as an innovator in the outdoor industry.

One of the major innovations that Mad River introduced, for example, came about in the early 1970s when the Henrys approached the DuPont Company to see about constructing canoes out of a new material that DuPont had been using to make tires—it was durable and strong and lightweight, but had never before been used to make sporting goods. Mad River introduced the first Kevlar canoe in 1974. “That was before it was even called Kevlar,” Henry says. “Now it’s in golf clubs, skis, everything.”

After the Henrys divorced in the mid-1980s, Kay bought out Jim’s share of the company, and as the female president of a sporting goods company—“a hard-goods company, not clothing,” Henry points out—she became something of a pioneer. “I was the Lone Ranger,” she says. “You had to prove your credibility.” It helped, Henry says, that she was “fairly financial. People think a woman doesn’t know numbers. That was an important strength.” In fact, Henry started out as a math major at Brown, but switched to geology because it was a “really good and fun and logical” department. She says that the most important thing she learned at Brown was not necessarily specific information but the skill of “learning how to get information.”

Another aspect of her business success, says Henry, is that she is a fierce competitor who’s sure of her own smarts and savvy. With any project, she says, “I expect to build something better than others do, and I don’t usually stop until I feel I have achieved a good portion of that.” (The Mad River logo—a smoking rabbit—represents self-confidence and, let’s be honest, a little cockiness. It comes from a Native American legend that envisions a rabbit so sure of his own speed that he can sit in the bushes, smoking his pipe, even as his mortal enemy, the lynx, lurks nearby.) Henry’s leadership style was to be clear about the company’s overall vision and direction, and then hire talented people who were passionate about the outdoors and whom she could set loose from there. She encouraged teamwork among her staff and let them try out some pretty crazy ideas, even launching, for a short time, Mad River Canoe paddling tours. The company was committed to “making this a lifestyle instead of just a manufacturer,” recalls Kay’s husband, Rob Center, who served for many years as vice president of marketing and sales. “Kay always believed that we’d sell the product if we sold the sport.”

She certainly believed in the sport. There was the time when she and Jim took their son and daughter, aged seven and nine at the time, on a three-week canoeing trip in the Yukon. “It was really great until it snowed two inches,” she recalls with a laugh. “We were miles from our scheduled pickup point. That’s when I learned to handle a canoe: when I had a child in the bow who didn’t want to leave his sleeping bag.”

In 1989, Henry and Center traveled to Finland to launch the Mad River brand there. The local distributor asked if she and Rob would join them in the weeklong, 350-mile annual Arctic Canoe Race, which runs from above the Arctic Circle clear through Scandinavia to the Gulf of Bothnia. Not knowing quite what they were getting themselves into, but having been in enough canoe races to be willing to take a chance, they agreed. “They woke you up at 1 o’clock to get you ready for a 3 a.m. start,” she recalls with a laugh. “You’re above the Arctic Circle so it’s light all the time. We finished that first night at 7 p.m.” The race featured Class IV rapids, twenty-foot waves, and one spot where they actually had to get out and swim. Dinner was reindeer. “We had seven nights of reindeer. And all you wanted was pasta!” The couple took first place in their class.

It was ultimately Henry’s love for the outdoors that drove her to sell the company, in 1998, to a private equity firm. “Suddenly it got to be really discouraging,” says Henry. “You couldn’t take a summer vacation because you spent the summer planning for the new line. That was getting to me. You weren’t as close to the product anymore as the company got bigger. Now it’s fun to have the freedom to get involved in issues you want to get involved in.”

Since selling Mad River, Henry and Center have hiked and paddled all over the world. Several years ago they went to Tanzania to climb Mount Kilimanjaro (like most experienced outdoorsmen, Henry refers to it affectionately as “Kili”); last year they traveled to Bhutan, where they trekked through the Himalayas. They stash a number of canoes in the tiny town of Norman Wells, on the MacKenzie River, in the Canadian Arctic, and take a three-week trip from there each year, paddling various rivers in the barren lands. A pilot flies them out with a boat and a GPS, and they arrange to meet again at a set latitude and longitude, on a set day. “You really do have to be prepared,” says Henry. “And you have to be self-reliant. That’s one of the things that I love about being out in a boat: you’re on your own. And that’s a feeling we don’t have very often in this world of cell phones. Cell phones don’t work up there.” Last year, on the Hornaday River, they were rewarded for pitching themselves headlong into the wilderness when they paddled through a herd of caribou that had just calved: moms and babies, fuzzy and weak-legged, nosing around in the snow. And Kay Henry, as always, on the river.

Canoeing, as it turns out, is as much about seeing the natural world from another point of view as it is about actually paddling a boat. At least, on this day it was. Henry explained that on trips through rapids and other tricky terrain, she “reads the water” from the stern, taking the long view to follow the fastest current and chart a safe path for the boat, while from the bow, Rob is the quick strength, making practiced pry strokes, draw strokes and cross-draws to navigate around rocks and other obstacles. For my beginner trip, however, we meandered and splashed, the paddles periodically making a pleasant clunk on the hull as birds called out raucously. We paddled past several floating logs where knots of turtles lay sunning, small and flat and green-brown; they flopped noisily into the water as we went by. Henry pointed out the herons among the birds that flew overhead, explaining that their wing beats are slower. We circled a beaver dam, glided past floating ducks, and saw cardinals, woodpeckers, and red-winged blackbirds, whose small black bodies were easy to miss until they exploded into the air in a flurry of red. We watched an osprey dive into the water and emerge with a fish in its gullet.

An avid backpacker, I looked down at my small but admittedly overstuffed day pack—for my first paddle, I’d neurotically packed everything from rain gear to a sweatshirt to a tuna sandwich—and it occurred to me that it’s much easier to toss a pack into the hull of a boat and paddle it than to strap it onto one’s back and walk. “That’s really what the Indians found out,” Henry said, “and that’s why they used these rivers as their highways. You can put a lot of stuff in a canoe.”

In the late 1990s, three paddlers and amateur historians named Mike Krepner, Ron Canter, and Randy Mardres set out to make a map of those ancient highways, and researched which routes the various North American tribes had used to move armies, to transport goods, and to hunt. Looking to promote their project, the men approached Mad River Canoe, whose catalog was as much “a storybook of what you could do, where you could go, with our products,” says Henry, as it was a vehicle for slinging boats. Calling the route Native Trails, one of the last catalogs the company published before Henry retired detailed a contiguous canoeing route through New England, modeled after the routes the Native Americans used.

And that would have been the end of it, until Henry and Center retired and were kicking around for a project. They called Krepner to see what had happened with Native Trails. “At first we thought, we can go raise money for them. We’ll help them,” Henry says. Then they realized that the project was still very much just an idea, a hobby, and that if it was going to go anywhere, they would need to bring the full force of their expertise, connections, and outdoor industry know-how to bear. They got the nod from Krepner, Canter, and Mardres, raised some money from their former colleagues at Timberland, L.L. Bean, REI, Thule, Old Town, and Eagle Creek, among others, and set to work.

Rechristening the project the Northern Forest Canoe Trail, they worked with private landowners, including timber companies, to arrange for portage sites, where paddlers must carry their canoes from one body of water to the next. They worked with congressional delegations, raising $250,000 in federal funds. They published thirteen different waterproof maps of the various sections of the trail. And they identified the “firecracker,” in Henry’s words—the mover and shaker, the visionary—in each small town along the route, to help plan itineraries and make a long-term plan for tourism. On June 3,2006—National Trails Day—the Trail was officially opened, with an event held simultaneously in four states, in pouring rain.

“The Northern Forest Canoe Trail started as a wonderful vision and has become a reality, thanks in large part to the efforts of Kay Henry,” says Vermont Senator Patrick Leahy, who helped Henry and Center secure federal funding. “Kay has exemplified a gracious persistence when seeking support for the Trail from the National Park Service, and that persistence has been complemented by a sincere understanding of and sensitivity to the local residents, partners, and communities along the route.” Coming up is a guidebook, which will provide a written narrative of the entire trail. Farther off, Henry envisions local state-based chapters to take responsibility for stewardship of their portion of the Trail.

One of Henry’s favorite words is “fun.” It’s a word that others might imbue with at least one part irony (as in, “We dropped our maps in the river and had no idea where we were. That was fun.”). But Henry almost always means it sincerely. It’s as if she’s taken the motto made famous by fellow Vermonters Ben and Jerry—“If it’s not fun, why do it?”—to heart and carried it with her to all her undertakings. Speaking of her time at Mad River, but in words that apply equally to her current project, she says, “I loved it. I was very happy being in a canoe as well as in the business world. Problem solving is fun. [The product] was good quality, it was going to last and do what [customers] wanted…. It wasn’t trying to be bigger than you were. A pipe-smoking rabbit you can have a good time with.”

After an hour and a half or so of quiet paddling, we drifted into the delta where the Missisquoi empties into Lake Champlain. Herons were everywhere: perched on rocks, drifting overhead, their beaks full of branches and brush for their nests. The treetops were jam-packed, not a single branch unburdened by the twiggy nests, which looked from the boat like messy pom-poms decorating the sky. Huge and graceful, the herons’ bodies floated across the sky, their playful racket fortifying us for the paddle back against the wind. Like an old hand, I dipped my paddle back into the river, and Henry and I pushed off toward home.

Beth Schwartzapfel is a BAM contributing editor. Find more information on the Northern Forest Canoe Trail here.