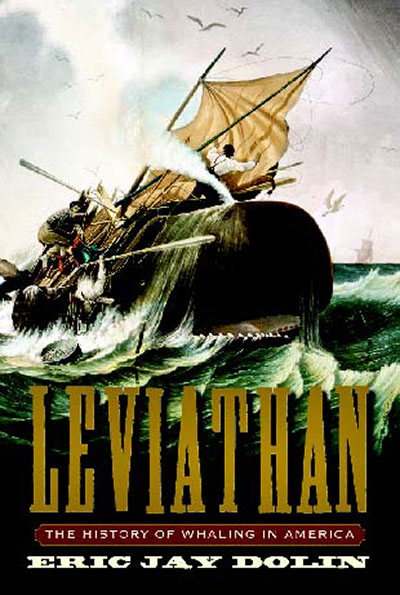

Leviathan: The History of Whaling in America by Eric Jay Dolin (W. W. Norton).

Eric Jay Dolin aptly describes leviathan, his history of the U.S. whaling industry, as a “maritime tapestry.” Weaving together economic, social, and natural history, his book is a lively, engaging, and well-constructed account of whaling’s impact on the United States from the early colonial years until World War I.

Dolin pays particular attention to the colonial establishment of whaling, and Nantucket necessarily plays a central role in that story. The American whaling industry began when coastal communities found, then searched for, squabbled over, and sold the byproducts of whales that drifted dead or dying onto their shores. Soon, local fishermen began to search offshore or to venture into “ye deep” to haul in larger prizes, and between 1712 and 1750 Nantucket thoroughly dominated this nascent colonial industry. Within its context, Dolin examines European conflicts, primarily British and Dutch struggles for dominance.

Dolin’s assessment of the mercantilist origins of conflict is reasonable and well researched. However, he arguably overemphasizes the importance of taxation without representation as the primary cause of the Revolutionary War, losing a more nuanced view of the war and diluting his focus on whaling.

In addition to detailing techniques for capturing, cleaning, and processing whales, Leviathan offers a strong account of whaling’s vital economic importance. In 1721, Dolin writes, “America’s negative trade balance with Britain stood at two hundred thousand pounds and was still growing.” But over the next forty years whaling offset that imbalance. “Between 1768 and 1772,” Dolin writes, “the sale of whale oil and baleen provided New England with its single largest source of British sterling, accounting for just over 50 percent of all the remittances coming directly from the mother country.”

American merchants reminded the London government that clean and clear-burning spermaceti oil could reduce crime by illuminating dark city streets. Obadiah Brown established a spermaceti candleworks in Providence in 1753, and the labels for Nicholas Brown and Company’s candles sported engravings of whaling scenes and were printed in both French and English.

With a flourish, Dolin recounts classic whaling “tales” such as the U.S.S. Essex’s heroic raid on British whalers during the War of 1812. He describes the damage inflicted on twenty-five Union whaler ships by the Confederate Shenandoah and the destruction of a late-nineteenth-century Arctic whaling fleet by pack ice.

Leviathan also captures the social history of the times: the boredom and terror onboard ships, the art of scrimshaw, the brutality of captains’ punishments, and even the allure of naked native women on the Marquesas Islands. And, of course, like Melville in Moby Dick, Dolin goes to some length to explain the physiognomy and behavior of the whales central to his story.

Leviathan is a timely reminder of the debt we owe these magnificent creatures. In fact, on October 1, 2007, the National Marine Fisheries Service will implement new rules to protect endangered migratory whales off the East Coast, where fishing gear and submerged lobster lines threaten to entangle them. Among those most at risk are the 350 remaining right whales that have survived despite all these centuries of hunting.

Ted Fitts teaches environmental history at Boston University.