If there is an unsung hero in the campaign to keep cigarettes out of the hands of children, it is almost certainly Judith Wilkenfeld. Starting in 1980, when she went to work as a lawyer for the U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC), she worked tirelessly to tighten government regulations on tobacco-industry advertising. Eventually, as vice president of international programs for the nonprofit Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, she took her campaign global, getting the World Health Organization to ease certain trade agreements so countries had greater freedom to impose regulations on cigarette sales to kids.

“The world lost more than one of its most important tobacco-control leaders,” Matthew Myers, president of the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, wrote in an obituary published in the August edition of the journal Tobacco Control. “What made Judy Wilkenfeld unique were the ways she brought people together, made everyone with whom she came into contact better, and became a close and trusted friend, confidante, mentor, and role model to so many people with whom she worked.”

Wilkenfeld, whose maiden name was Plotkin and who died of pancreatic cancer on May 24 in Washington, D.C., began her career in government in 1969 at the National Labor Relations Board. She focused on labor law until the FTC offered her a job as its point person on tobacco issues at the start of the Reagan administration. Her husband, Jonathan, says she quickly became consumed with the issue. “I don’t know whether she was a zealot to begin with, but eventually she became one,” he says.

At the FTC, Wilkenfeld was the lead attorney in several cases against tobacco companies, including the 1990 litigation against the R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company for misrepresenting the health risks of cigarettes in its ads. She also spurred the agency to sue R.J. Reynolds over its use of the cartoon character Joe Camel, which she saw as a backhanded way to market cigarettes to children. “It was the kids that motivated her more than anything else,” says Jonathan Wilkenfeld. She believed “that there should be clear warning as to the consequences of cigarette smoking and there should be no advertising to particularly vulnerable communities.”

In 1994, Wilkenfeld was hired by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to be the agency’s special adviser for tobacco policy. At the FDA she fought for a new federal law regulating the sale of cigarettes. Even though the agency can regulate food and drugs, the U.S. Supreme Court has ruled that it cannot regulate cigarettes without further Congressional legislation. “She negotiated this big piece of legislation which ultimately didn’t go anywhere,” her husband says. Frustrated, she left the FDA in 1999 because, Jonathan says, “she just had had enough of that battle.”

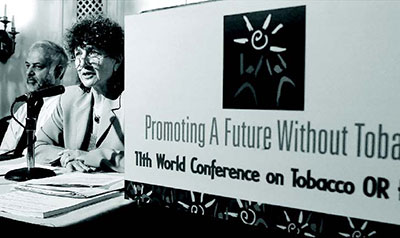

For two months, he says, his wife “hung around playing with her grandchildren,” but then the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids offered her a job and she took it. She spent the next four years in Geneva working to create an international treaty committing countries around the world to banning tobacco advertising and adapting tax policies that discourage cigarette smoking. The so-called Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) went into effect in 2005, becoming the WHO’s first-ever global health treaty. “Without her work, it’s unlikely the Framework would have happened,” her husband says.

The agreement has been signed by over 150 countries, though the United States still has not done so. In 2002, Wilkenfeld lambasted the Bush administration for not supporting the tobacco treaty at a public hearing before the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. “The Administration’s refusal to back provisions in the FCTC that prioritize public health over the interests of the tobacco industry is particularly troubling given our nation’s role in spreading tobacco-related addiction and death through our foreign-trade policies,” she testified. “The world’s most powerful nation should not now be adding to this sordid history by using its diplomatic and economic might to promote the interests of the tobacco industry and add to the tremendous toll in disease and death that tobacco use takes around the world.”

Wilkenfeld is survived by her husband Jonathan; three children; a brother; and three grandchildren.

—L.G.