On September 1, 2001, Christine Montross held a human heart in her hands for the first time. It was her first day at the Warren Alpert Medical School, and already she was doing the thing she’d been dreading ever since she’d made the decision to become a doctor. The heart reminded her of cooked chicken. As she probed its chambers and valves with her fingers, she was unnerved to discover that the atrium felt as thin as an old T-shirt. A tear would mean instant death.

At twenty-eight, Montross was older than most of her classmates. She’d spent the years since college writing poetry and teaching English to high school students, but she’d decided to change careers. Now she stood with the other members of her class in Brown’s human anatomy lab, cutting into the flesh of a human being. The air around her was sharp with the smell of the formalin-and-alcohol embalming fluid used to preserve the eighteen cadavers, which lay on stainless steel dissecting tables. The seventy-two members of the class were assigned to teams, four students to a body.

Montross examined her cadaver. Before her lay a slender old woman, whose long, thin arms were mottled with age spots. “They are surely the arms of an old woman who has spent time in the garden or at the lake,” Montross reflected. She remembered massaging her grandmother’s arms for weeks after she’d suffered a stroke earlier that summer. All Montross knew about the woman before her was her age (eighty-two) and her cause of death: breast cancer, a fact made obvious by her surgical scars. Oddly, the woman had no umbilicus. Her abdomen was wrinkled, but otherwise smooth—no scar tissue indicated that a surgeon’s hand had inadvertently sewed up her belly button. Montross and her teammates would never solve this mystery, but they were sufficiently moved by it to call the woman Eve.

When doctors reminisce about anatomy lab, they sometimes sound like soldiers rehashing basic training. The course is famously grueling—emotionally, mentally, and physically—and it lends itself to black humor, a staple of which is the nickname “Woody” commonly given to male cadavers with rigor-mortis erections even years after death.

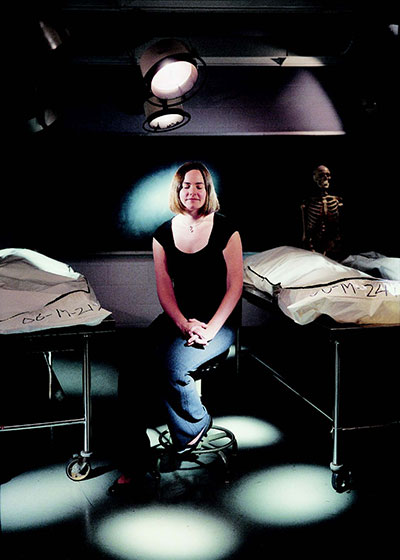

But give a poet the task of describing the experience of gradually cutting a human body into pieces and you come away with a much richer story. Now a second-year resident in psychiatry, Montross has written a memoir, Body of Work: Meditations on Mortality from the Human Anatomy Lab, published this summer by Penguin Press. By turns funny, disturbing, and reverent, it’s the story of her first semester of medical school and the lessons she learned about life from studying the dead.

In Montross’s day, Brown’s first-year medical students spent all day every Tuesday and Thursday in anatomy, breaking only for lunch. The curriculum has since changed, but the course is still brutal. Many students return to the lab after dinner—punching their key codes into the door lock and unzipping the body bags that hold their cadavers. Students often stay late into the night, anxiously trying to figure out how some elusive piece of the body fits together and works. Professor Emeritus Ted Goslow, who taught the course for fifteen years until his retirement in 2005, says that when he first came to Brown he wanted to lighten the load by holding shorter labs three afternoons a week, as is now common in many medical schools. But his students said they preferred the immersion of two long days, so he kept the existing schedule. Montross was one of his students.

Guiding students through their lab work is an infuriating textbook called the Essential Anatomy Dissector, which Montross calls simply The Dissector. In her memoir, it’s a stern presence, tersely dictating instructions that sound simple but bear no resemblance to the jumble of tissues students must sort out in the bodies before them. Over the course of four months, first-year students must master tens of thousands of pages of material (“a bottomless pit of information,” Goslow says)—memorizing and regurgitating the names and functions of blood vessels, nerves, joints, muscles, ligaments, and bones.

Then there’s the emotional transition, which can be even harder. Students begin the journey that will turn them into doctors—into healers—by cutting a human body apart. To do so, they must quell their fears and their revulsion, some of their most basic human instincts. When Montross entered the anatomy lab for the first time, she was so nervous that she instantly forgot the three-digit key code she’d just learned to unlock the door. Goslow warned the class, “[If] you see someone talking but you can’t hear them, sit down, because it means you’re going to faint.” That part she remembered.

Most of her classmates were twenty-one or twenty-two years old when they picked out their first lab coats for anatomy. Participants in Brown’s eight-year Program in Liberal Medical Education (PLME), they’d been admitted to the College and the medical program straight out of high school, and some had known one another all their undergraduate years. For most of them, the transition to medical school seemed largely a matter of adapting to a new curriculum.

To balance the youth of the PLME students, Brown often rounded out the class with men and women who’d worked for several years. Montross was one of these older students; so was one of her lab partners, Tripler Pell ’05 MD, a former ballerina who had earned a master’s degree in the history of medicine. In addition to maturity and life experience, Montross brought to the classroom a poet’s insights and a teacher’s instincts. She’d studied French literature and environmental science as an undergraduate at the University of Michigan and had stayed on to earn a master of fine arts in poetry in 1998. She’d had poems published in the literary journals Calyx, Witness, MacGuffin, and Alligator Juniper, and taught at Michigan for a year. Then her partner, playwright Deborah Salem Smith, whom she’d met in graduate school, announced she’d had enough of Michigan winters. The two moved to San Francisco and took teaching jobs. Montross joined a charter school for at-risk high school students, and midway through the year she knew that the teenagers in her classes suffered from psychiatric and social problems no poem could touch. She became increasingly frustrated by her inability to help them. Her mother is a psychiatric social worker, and Montross considered following in her footsteps. She’d always been fascinated by the intellectual idea of madness and had written about insanity in her poems. With so many recent advances in brain science, she figured psychiatry was the field that offered the greatest promise for curing mental illness. She decided to apply to medical school.

First, however, she had to take all the pre-med courses she’d missed in college. She enrolled in a yearlong crash course at Bryn Mawr College, in Pennsylvania; Smith and their cocker spaniel, Maggie, moved with her. Montross struggled through physics but completed the program and was admitted to Brown’s medical school. Having lived in Indianapolis all her life before moving to Ann Arbor for college, Montross jokes that not only had she never been to Rhode Island, she’d never met anyone who had been there. “Deborah tells people I presented her with false credentials,” Montross says. “She thought she was getting involved with a poet, not a doctor. She didn’t bargain on my wearing a beeper all the time.”

To keep in touch with her old writing self during the long fall months of dissecting and memorizing, Montross kept a journal. After lab, she’d return home, take a hot shower to scrub the bone dust and embalming fluid from her pores, and sit down to write about the day’s experience. She took notes on the dissection she’d performed that day and reflected on the philosophical and emotional issues it raised. Frequently, she found herself wrestling with the irony that doctors learn to heal by dissecting the dead. She monitored the process by which she shut down some of her emotional responses, gradually developing the distance she needed to become a doctor. Dissection pervaded her life and dominated her dreams. “Most nights, in the dream space between wakefulness and sleep, I am skinning people,” she wrote. “Not that I can see myself standing at the table in lab. It is just my hands, and the left pulls back skin from some unidentified part while the right fingers sweep away the fascia beneath.

“It does not feel depraved. It is the slight annoyance I felt as a breakfast waitress when, in the same near-sleep moments, I would think Syrup to table twelve. Extra butter to twenty-six. As then, I wake myself with logic—there is nothing to do now but sleep. Nothing to do but rest. Then eyes closed, deep breaths, and the returning pull of the left, sweep of the right.

“Wake, logic, breathe, left pull, right sweep, wake.”

Intrigued by her experience, friends and family barraged her with questions: how did it feel to take a scalpel to a human body? The depth of their fascination prompted Montross to believe her journal entries might hold the key to something longer—an article, perhaps even a book. So she showed her notes to Goslow, asking him if the department might give her some financial support so she could write over the summer.

“I read those notes and said, ‘Whoa,’ ” Goslow recalled in a phone interview from Bend, Oregon, where he now lives. In the classroom, Montross had struck him as an interesting student for sure, but one among many. Her astute observations on paper, however, took him aback. The medical school already offered summer fellowhips for students doing clinical and research projects; the deans added another in the arts and gave the first grant to Montross. Goslow and other faculty encouraged her to undertake a second degree, a master of medical science; her book would be her dissertation.

The spring before Montross’s final year of medical school, Smith received a Fulbright grant to travel to Ireland. Brown allowed Montross to take a year off to work on her book, and the two women moved to Dublin, where Montross attended autopsies and researched the history of human dissection at the Royal College of Surgeons. She toured the famous European anatomical theaters into which sixteenth- and seventeenth-century medical students crowded to watch their professors dissect illicitly obtained cadavers. Performed without modern embalming techniques, those early dissections were a race against rot, and the stench of decomposing flesh must have been overwhelming. Montross describes students packed tightly against one another to prevent those who fainted from pitching forward over the rails.

She was intrigued by the Catholic Church’s paradoxical responses to the question of human remains. On the one hand, from the Renaissance on, the Vatican tried to curtail human dissection, and medical schools bought cadavers on the black market from grave-robbers. But on the other hand, the Church seemed obsessed with the abundant remains of its saints. Europe’s churches are packed with reliquaries and crypts where the faithful can pray to Saint So-and-So’s scapula or femur. Montross took Smith to Italy to see the intact body of St. Catherine of Bologna, whose corpse was taken from her grave and installed on a golden throne for all to see. The two writers marveled at the bizarre chapel of Santa Maria della Concezione, built in Rome by the Capuchin monks, who decorated the walls with a filigree of human bones—all remnants of the monks’ belated brethren. “I gave Deborah the most ghoulish tour of Europe imaginable,” Montross says wryly.

It was an immensely productive year, though. The couple returned to the United States in May, 2005, and by June, with the help of a friend who served as sperm donor, Montross was pregnant. “Deborah calls it the year of births,” Montross says, beaming. Smith had been reading scripts for Trinity Repertory Company in Providence, and was commissioned to co-author a play about Rhode Islanders’ ties to the war in Iraq. Baby Maude was born in December, and Smith’s play opened a month later.

While writing, Montross had learned of a competition for young writers that carried a prize of $25,000, so she entered her work-in-progress, figuring the cash would help with tuition. She didn’t win, but she was a finalist and she began getting calls from literary agents. She signed with one and received a sizeable advance from Penguin to produce Body of Work.

In person, Christine Montross is hard to miss. At six-foot-two, she stands out in the Miriam Hospital emergency room, where she was assigned this summer. Montross says she’s the shortest in her family; her seven-foot-tall brother, Eric Montross, played in the NBA for fifteen years. She wears her thick brown hair cropped just above her shoulders and has a wide smile and an easy, comforting manner as she pulls back the curtain to interview a patient. She asks intensely personal questions with grace and courtesy, probing respectfully but pointedly. Now in her second year of residency, Montross is rotating through psychiatry jobs in various Brown-affiliated hospitals. She’s also in the midst of a book tour, juggling requests for readings and lectures at medical schools, interviews with National Public Radio, and a trip to Washington, D.C., for a C-Span taping. Plus she’s writing again; this fall she has two articles coming out in O, Oprah Winfrey’s magazine.

On the home front, Maude is now a very active (and very tall) seventeen-month-old. Normally, Smith writes at home in the mornings while a baby-sitter tends Maude. But Smith has a second play making its debut at Trinity this season. And Montross just finished a month of long, all-night shifts, which took a stiff toll on her health. Smith’s father came east to visit and help out. “Camp Grandpa,” Montross calls it.

“We’re pulling it off by the skin of our teeth,” she says, with a wince and a smile. “Deb and I have realized that we both have careers we really care about and we’re both really committed to parenting. Normally, I have a lot less flexibility than Deb does, but right now...” She lets the sentence hang. “It’s all goodness. If our only complaint is that we’re really busy, that’s not really a complaint.”

Even as Montross glances down at her beeper and fields telephone and e-mail requests, she exudes confidence, poise, and extraordinary competence. “She is so very organized,” says Goslow, “and she hits every aspect of her life head-on.”

That she turned a routine course in anatomy into something as rich as Body of Work seems right in character. Although the book had its origins in a master’s thesis, the memoir became much more than that—a bequest, finally, to her teachers. After her final anatomy exam, Montross writes, she returned to the lab, punched in the code she had initially had such trouble memorizing, and looked for Eve. Montross unzipped the body bag, uncertain of her intentions.

“I touch her brain, resting in the upturned dome of her skull,” she writes. “I touch the bare bone of her face, her shoulder, her pelvis, her leg. My hand comes to rest in hers. I feel her vessels beneath my fingers, her tendons, and bones.”

Montross was one of Ted Goslow’s last students; she mailed him a copy of Body of Work when it came out this summer. He says he felt a little trepidation as he read. “I’d watched the evolution of Christine’s attitude throughout this process, from the first placing of a scalpel on the human body to the end,” he says, “but I had no idea where this was going to go.”

What he learned was that Montross saw the cadaver as a teacher.

“Eve has become a gift to her,” he said. “As a teacher, I could not have asked for anything more.”

Charlotte Bruce Harvey is the BAM’s managing editor.