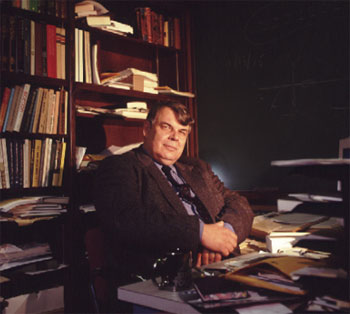

Sitting at the white melamine conference table that crowds his office, Alexander Levitsky shakes the ashes from yet another cigarette. The table is covered with papers and journals, as is every other horizontal surface in the room. Bookcases stretch eleven shelves high, packed solid - Pushkin and Poe interspersed with sci-fi paperbacks. "I am a glutton for books," Levitsky says.

Clouded with smoke, his office brings to mind a Russian kitchen - the underground equivalent of a literary caf}. The space feels both poetic and political, romantic and radical. To Levitsky, literature seems at once a matter of the senses and a means of social change, a theme that manifests itself in Russian 120, Russian Fantasy and Science Fiction, which he has taught for nearly twenty years.

The course's content belies its escapist-sounding title. In Levitsky's view, "fantasy-making is the stuff of not only escape but human progress." It is fantasy, he says, and the imaginative thinking it inspired that moved the Soviets to send Sputnik into space and the Americans to land Apollo 11 on the moon. Ultimately, Levitsky argues, this ability to imagine a better future is also what led to the fall of the Soviet Union. To him, fantasy may be an escape, but it is one whose value lies in breaking the chains that confine the human spirit. Fantasy is a bridge between the reality of today and the prospect of tomorrow.

"The main thing about this type of literature," he says, "is that it can trigger something that I believe makes us human, trigger that element of idealism that allows you to move beyond your present-day reality. A true work of fantasy continues breaking down preconceived spaces through providing new shifts, new settings, new labyrinths of understanding. And that's the process of learning."

Levitsky begins his course with Russian fairy tales, particularly the stories of the transformation of peasant boys into czars. From there it goes into the early Romantic period of Russian nineteenth-century literature, which is marked by dreams, a common characteristic of the fantasy genre, Levitsky says. "Then we move on to the first honest-to-goodness mixed-up world of intersecting realities and fantastic fusions - the world of Gogol, of course." In Gogol's The Overcoat, the protagonist's long-coveted new coat gets stolen, and the petty clerk dies in the St. Petersburg chill. His phantom, however, reappears in a fantastic city, resembling St. Petersburg, where ghosts are allowed to steal overcoats, Levitsky says, "as a final form of vengeance of the fantasy over reality."

St. Petersburg figures prominently in Gogol's short stories, as it has for the Russian imagination more generally, according to Levitsky. The city's construction in the eighteenth century opened new vistas for Russia, tapped its imaginative force, and paved the way for its entrance into world literature. In Levitsky's office are several images of St. Petersburg. One, a framed print, hangs high atop the bookcase behind his computer. On a windowsill he has propped a modernist stained-glass panel whose blue and green squares are pierced by triangular yellow rays. It is one of four panels created by a former Russian 120 student in response to Andrei Bely's Petersburg, a novel that is filled with imagery of shapes. The city's founder, Peter the Great, "achieved something of wonder for Russia," Levitsky says. "He started building the most modern, the most futuristic city on the face of Europe - a city with avenues wide enough to accommodate twenty-first-century traffic, a city of vision, a utopian city." Utopian and anti-utopian, or dystopian, themes pervade the readings in this course - fairy tales, symbolist literature, and science fiction.

"Some of the utopias we read did not seem so utopian from our point of view," says Megan Wachs '05, an engineering concentrator who had never read any Russian literature before this course. "Like they talked about how warm it was going to be." After Stalin's death in 1953, the Soviet Union experienced a political and artistic warming. "That thaw," Levitsky says, "allowed for the first time for Russian poets to sing of love. No longer were readers forced to travel on Russian steppes and see tractor drivers hard at work cultivating the land, no longer did they have to see the travel of Russian troops toward Berlin. New young Russians who were born after the Second World War had something to look forward to."

To pass the state censors, Ivan Efremov's novel Andromeda needed merely to state in a sentence that Communism would persist a thousand years into the future. ("A bad book," Levitsky says, though he recommends it for historical reasons.) Soviets read these new fantasies greedily, passing them along in an underground reading chain. "You could not hold these books for more than six hours," says Levitsky. "That's how popular this genre as a whole became for freeing the Russian mind."

In 1989 Soviet television aired a film based on Mikhail Bulgakov's novel Heart of a Dog. It showed the housing authority invading an old doctor's residence and forcing random roommates into his space, enforcing the early Soviet concept of the communal apartment. The pain and absurdity of the new law underscored the fact that the Soviet government did not miraculously land in the Winter Palace and smoothly take control of Russia; rather, as Levitsky says, "power was achieved by continuous dispossession of people by bands that could best be described as state-sponsored terrorists." He concludes, "It was this work of literature that has finally moved the general Russian audience to come to the point of the unthinkable, namely the lifting of the rule of the party."

THE ROOTS OF RUSSIAN 120 can be traced to the late 1970s, when a group of students asked Levitsky to sponsor a Group Independent Study Project (GISP) on science fiction. Although his own literary interests were more arcane (Russian eighteenth-century poetry), he was teaching the popular introductory class in Russian literature and possessed a huge collection of science fiction books. The 1970s, he points out, were a hot era for Russian studies, including Russian literature. The GISP evolved into a regular course offering, and twenty years later it still draws a steady stream of students - thirty-nine this spring, many of them new to Russian literature.

The course's origins go deeper, though - back to the events that prompted Levitsky to study literature in the first place. Although his family is Russian and he grew up speaking the language, Levitsky spent his childhood in the Czech Republic. (A large map of Old Praga hangs in his office.) Twenty of his relatives were killed in Soviet purges. On his seventeenth birthday, in 1964, Levitsky escaped to Paris, having illegally crossed Yugoslavia and Italy. Four months later he arrived in the United States, where he pursued premed courses at the University of Minnesota (he completed majors in four disciplines).

It was not until 1970, at age twenty- two, that he ventured into Russia for the first time, landing in Leningrad in a February snowstorm. There, he says, "I met many Russians who felt in me a free Russian, and they loaded me with litanies of their biographies and with a very heavy burden of guilt. I started to do literature as a guilt thing - that they are there and can't publish and I am here and free and can."

That's the political side. If you push Levitsky further, though, you may find that the seeds of today's course were sown earlier still, in the Czech Republic of the 1950s, when a six-year-old boy read a pocketbook of Gavril Derzhavin's eighteenth-century verse. (Levitsky has just published a book of Derzhavin's poems in English and Russian.) "It was this man," says Levitsky, "who opened up for me literature, poetry, and fantasy or the fantastic worlds." The poems created unseen but tangible new spaces, he says, "worlds that I could taste."

Yuliya Chernova graduated from Brown with honors in May. She is currently a freelance writer and researcher in New York City.