Sweet: An Eight-Ball Odyssey by Heather Byer ’90 (Riverhead/Penguin).

On Columbus Day, 1998, Heather Byer walked into her first pool hall. A perfectionistic Midwesterner who’d come to New York City after Brown and was now running the Manhattan office of a big feature-film company, Byer was looking for something—an antidote to her weekday life eating business lunches with narcissists and pitching story ideas to her spoiled-brat Hollywood boss.

Pool’s solitary, exacting nature and the dark, smoky dens in which it is played seemed to promise a respite. Byer wasn’t looking for a boyfriend, or life lessons, or psychotherapy. What she wanted, it seems, was to lose herself in a game so intense and absorbing that it would blot out all her other concerns.

But, of course, that’s not how things turn out in this often wittily observed and elegantly written memoir.

Byer begins her adventure with pool by taking weekly lessons, and after nine months she’s asked to join a team playing in a league. She’s recruited because she’s a novice, and to comply with league rules the team needs to round out its roster of heavy-hitters. First night out, pitted against a top-ranked opponent, she hits the pool equivalent of a Hail Mary shot. She’s hooked.

Instead of the solitude she thought she was seeking, Byer finds a community that offers real friendship. She also becomes enmeshed with some pretty messed up folks. One player is hauled out of a bar when he slugs an opponent for the sartorial sin of wearing Birkenstocks and chinos. A well-heeled lawyer loses his girlfriend, his savings, and ultimately his belongings to alcoholism. We never learn whether he loses his life as well.

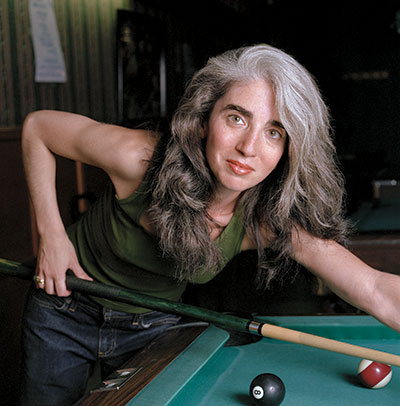

Byer changes along the way. At the outset she’s attracted by the cerebral side of pool, its strategies and its mathematical determinacy. She compares the game to baseball, which she adored as a child, rooting for Reds catcher Johnny Bench. No athlete, she quit softball after a season and took up pottery. But despite the fact that pool doesn’t come naturally to her, she sticks with it and along the way discovers some latent physicality inside herself. Before you know it, this self-described A student is squeezing herself into low-slung jeans and swinging her long dark hair (with its trademark white streak) every which way, and reveling in the compliments men give her on her sexy arms and her womanly way with a cue stick.

From the start, Byer claims she doesn’t care about winning or losing; she’s not competitive, just perfectionistic. She argues that this is the difference between the way men and women play. Then after a prolonged slump her rank is downgraded to a rock-bottom two, and she’s both mortified and furious. She wants a win, and she doesn’t care how she gets it.

Geek that she is, Byer fights her losing streak by studying pool. She digs into the debates about its origins (England and France both have viable claims; but then so do Persia, India, China, and Russia… no one knows). The word pool comes from the French poule, a betting term, she reports, and American pool developed a bad rap in the early twentieth century because it was played in the same betting establishments where people were playing the horses.

Byer has a sharp eye, and some of her sketches of the folks she encounters in New York are side-splittingly funny. There’s Mitchell, the hotshot “lad-mag” editor who’s pitching movie ideas over lunch. She finds him sitting at the restaurant’s bar, wearing sunglasses and reading a magazine: “He wears a black suit over a black T-shirt, and glossy black motorcycle boots. As I look from magazine cover to man, I realize it’s him, it’s the same guy, the editor of the year, in the same pose, wearing the same clothes, the same sunglasses, reading about himself.”

Egos prevail in what finally emerges as a morality tale. When Byers is deep in her slump, a veteran pool player named Armand takes her on, advising her that her fear, her “constant clutching, is because of three letters: E-G-O.”

“ ‘Don’t worry,’ Armand says, ‘I teach you.’ ” And he does.

Charlotte Bruce Harvey is the BAM’s managing editor.