War is always with us, and as long as men and women are wounded in battle, doctors will try to save their lives. Every generation faces its own wars, waged out of their own particular political and diplomatic circumstances, but to military surgeons every war is the same. The wounded and dying arrive every day, and the doctors scramble to treat them. As physicians, they are sworn to protect every soldier and civilian, no matter what side he or she represents.

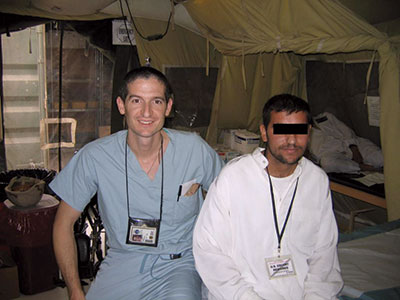

Chris Coppola ’90

It was midnight in late February 2005 when U.S. Air Force surgeon Christopher Coppola was called from his hooch to the hospital at Balad Airbase north of Baghdad. Coppola was accustomed to treating wounded troops brought in by helicopters, but before him tonight were two little girls with burns. Carrying them was their father, an Iraqi national guardsman whose home had been firebombed by an insurgent that evening. After two local hospitals had turned him away, he’d persuaded the guards to let him enter the Balad gate.

A pediatric surgeon by training, Coppola set to work giving the girls intravenous fluids and morphine. Then he cleaned their burns. The younger girl, who was a mere two weeks old, was only mildly injured, but her two-year-old sister was scorched from her waist to her toes. “I knew she was in much greater danger,” Coppola recalls.

The two girls were only the latest of the many civilians being killed and maimed in Iraq. The helicopters that dropped off wounded American and Iraqi troops often arrived with wounded civilians. When violence erupted, soldiers and airmen would load all the injured they could into helicopters, and everyone—the attackers, the attacked, and innocent civilians—would be flown to the tent hospital at Balad.

Most of the time, when they heard the drone of arriving choppers, Coppola and the two dozen other doctors on the base headed to the hospital whether they were on duty or not. Coppola usually waited at the edge of the helipad, where he could get a head start questioning the medics as they carried in the litters: Was this patient breathing on his own? Was that one conscious when they’d picked her up at the scene? Could another move his arms and legs? Did he need blood right away?

Inside, the medical techs would cut away clothing, monitor heart rates, insert lines for blood and antibiotics, and keep the patients warm. They’d roll the worst-off patients on gurneys to the operating-room door, where Coppola and his colleagues would stabilize their spines and check for breathing and bleeding. Then they’d moved into the O.R., treating the direst cases first.

Coppola learned to make decisions at warp speed, determining which leg he could save, or what muscle was going to die. He became adept at probing wounds to unearth splinters of bone, clots of mud and filth, or glass and metal fragments from the car bombings so prevalent in Iraq. “Day after day,” he says, “seeing people with over 100 pieces of shrapnel piercing their bodies, you get good at it.”

Although Coppola is not an orthopaedist, he learned to drill holes in bones and install pins, then attach external metal frames to hold legs in place. Occasionally he amputated an arm or a leg, discarding the limb into a red garbage bag. Then airmen would load wounded U.S. troops onto stretchers and set them in the belly of a C-17 cargo plane for the flight to a real bricks-and-mortar hospital in Landstuhl, Germany. Within hours of being wounded, the injured Americans would be gone.

Coppola figures that of the 1,200 or so injured that he and his colleagues treated during his five-month stint at Balad in 2005, more than a third were Iraqis. Fifty-five were children. “We were the end of the line for Iraqis,” he says. “There was nowhere else for them to go.” For example, Coppola and his colleagues operated twenty-five times on an Iraqi soldier injured while trying to prevent a suicide attack. After three months they transferred him to a local hospital, even though he still required a ventilator to breathe. He soon died. The Iraqi doctors, Coppola says, didn’t have a spare ventilator.

Day after day, Coppola returned to the burned Iraqi toddler, whose name was Marien. She cried when Coppola had to debride her burns, but at other times, this chubby girl with chestnut hair laughed and made her preferences clear: potato chips, Oreos, a pink teddy bear. She reminded Coppola of his own children. “She was the same age as my Reid,” Coppola says, referring to the youngest of his three sons.

When he’d volunteered to join the air force, Coppola had no idea that his obligation would coincide with a war. He’d wanted to take advantage of the service’s Health Professions Scholarship Program, which would put him through four years of medical school at Johns Hopkins. The program also provided support for two of his nine years of training in pediatric surgery. In return he agreed to serve six years as an active-duty air force officer, from July 2003 to June 2009.

So here he was, away from his family, treating Marien. After two weeks and thirteen visits to the operating room to remove dead tissue, she was well enough for a skin graft. Coppola harvested undamaged skin from her upper belly to graft onto her burned legs. The graft soon began to turn pink, a sign that blood vessels were forming in the graft. But two weeks later, Marien abruptly sickened. Bacteria had proliferated faster than her graft healed.

Coppola still remembers the date and hour of Marien’s death: March 24, 2005, 6:50 p.m. Security had been tight, so her father and mother had not been allowed in that day. Coppola wrapped Marien in a blanket and handed the small body to her father, uncle, and older brother at the Balad gate. He watched them drive away.

Back at the hospital, he sought out a fellow surgeon, Brett Wyrick, an air force reservist from Hawaii. “I sat down next to Brett, and I sobbed,“ Coppola recalls.

Wyrick handed him a Toblerone bar and referring to the soul-sucking fiends from the Harry Potter books, he said, “Eat this. It keeps the Dementors away.”

“It was the silliest thing to say,” Coppola recalls, “but it helped a lot.”

Strangely enough, death at Balad was the exception. Troops who died usually did so before arriving at the hospital. Coppola says that of the 3,000 Americans wounded gravely enough to be evacuated through Balad to Germany while he was in Iraq, he knew of only four who had died. Such success made Coppola feel useful. “I had the privilege,” he says, “of feeling that if I wasn’t standing there holding pressure on that artery, if I wasn’t cleaning out that person’s belly, if I wasn’t there, the person would probably die.”

Still, he says, “Each of these deaths is a destroyed family. I would make whatever moves necessary to make these deaths stop. To me, that’s pulling out.”

Talking to Iraqis confirmed his view that the war had been a mistake. An interpreter once told him: “We’re thankful you’d come over from your country, and we’re impressed that you’d risk your lives for us, but you’re never going to change Iraq.” Inevitably, the Iraqi told Coppola, some “Ali Baba” would take over. Ali Baba was a generic name for a despot, said Coppola, the anti–Uncle Sam. “I didn’t expect I’d be so against the war,” Coppola says.

Treating failed suicide bombers only reinforced the senselessness. Coppola talked to one apparent suicide bomber who was brought into Balad riddled with shrapnel from a bomb in the truck he was driving. The man told Coppola that fellow Iraqis had kidnapped his two daughters and threatened to kill him unless he parked the truck next to a target. They told him he could leave the truck before it blew up, but they detonated the charge remotely before he could escape.

“I’ve always known that I can never be sure about what happens outside the walls—or tent flaps—of my hospital,” Coppola says. “People lie and make themselves believe all kinds of justifications. But his story did make me wonder about many of the suicide bombers.” As Coppola expressed his doubts, he earned a nickname: the Senator from Massachusetts.

In response, Coppola tried to be the compassionate face of the military, putting a comforting hand on the shoulder of a blindfolded prisoner of war having his wound debrided: “You see people with their legs blown off. You see a child killed. The only response that I can come up with is that men are mad.”

To Coppola, a slow day in Iraq was a difficult day. “When you’re cutting off someone’s leg, you just do it, because they’re going to die if you don’t,” he says. “When you have nothing to do, you start thinking about it.” Coppola had trouble sleeping. His homesickness for his wife and sons was searing. “I would go over to the hospital and say, is there anything I can do? If the orthopaedists were doing a delayed operation, I’d scrub in as a med student.”

Writing home helped. Coppola put his thoughts down in e-mail messages written initially for his oldest son, nine-year-old Ben, and his wife, Meredith Leigh Norvell ’91, whom he’d first met in Zeta Delta Xi at Brown. Soon extended family and friends began reading the messages, and Coppola addressed himself to all of them. When he wrote of his yearning for hot sauce, someone would send him some. He gave progress reports on the cilantro and sunflowers he’d planted in the sandbags protecting his trailer. He told of waving to shepherds just outside the barbed wire as he ran laps in the 110-degree heat. He reassured Meredith that even when jogging, he had kept his promise to wear his thirty-five pounds of Kevlar body armor. He described the good-luck talismans he carried with him, especially his wife’s dollar-bill engagement ring. He also noted when he discovered he’d operated on the man who had thrown the firebomb at Marien’s house. He tried to buffer bad news with good, making each letter “a happy-sad-happy sandwich.”

Ben’s classmates began reading the e-mails. They wrote Coppola letters, and he answered every one. One fourth-grader asked: “What is the saddest thing you’ve seen?”

It’s been two years since Coppola returned from Iraq in May 2005. He is now stationed at Lackland Air Force Base in San Antonio, Texas, where the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan are very much present. Lines form at the gates as security guards check incoming cars and trucks. Traffic spills onto Military Highway as the 49,000 people who work at Lackland arrive for their shifts. Coppola spends his days at Wilford Hall Hospital, running the pediatric surgery service for the children of air force personnel and retirees. Because he is the only pediatric surgeon at any U.S. Air Force base, his patients sometimes arrive from far away.

Across Military Highway, new recruits run laps, do pushups, and learn to shoot. On Thursdays and Fridays they graduate from basic training at the parade ground a block from the hospital. More than 500 graduate every week, 28,700 each year. Behind the hospital, airmen train dogs to sniff out bombs. Beyond the generals’ little cluster of ranch houses, C-17s sit on runways, noses open for loading or repairs. Anytime Coppola’s not dressed in scrubs and his yellow, cartoony “surf’s up” surgical cap, he wears a camouflage battle-dress uniform—even to do paperwork. “We’re a nation at war,” he explains.

On a day last March, Coppola takes a break between meeting with a teenager scheduled for thyroid surgery the next week and examining a newborn with lung problems. He sits in his office drinking iced tea with a visitor and two medical residents and, as is often the case, he begins talking about the war.

Just as he is launching into a critique of the Bush doctrine of pre-emptive war, there is a knock on the door. A man in dress blues enters. He and Coppola look each other in the face for a moment before they embrace, separate, and embrace again. The visitor is Colonel Brett Wyrick, the surgeon who comforted Coppola after Marien’s death in Iraq. Wyrick is in town for basic-training graduation. Sturdy, sandy-haired, and stolid, he looks military to the bone—in contrast to Coppola with his unruly brown hair and animated manner.

Coppola tells Wyrick that he’s talking about the war. Wyrick laughs. He joins in the discussion. He argues that the U.S. invasion was justified and says he supports a surge of troops into Baghdad. “It grieves me that we’re still over there and losing so many people,” he says. Then he quickly adds, “You have to secure Baghdad. It’s an elected government, and you have to give them a chance.” He reminds Coppola of the Iraqi lieutenant brought into the hospital at Balad the day before the Iraqi election in January 2005. The man was badly injured but wanted to know if he’d be able to vote the next day. “That told me everything I needed to know about Iraq right there,” Wyrick says.

As the discussion continues, Coppola argues that there is no evidence connecting Saddam Hussein with the 9/11 attacks—in which Coppola lost a childhood friend from his hometown of Madison, Connecticut. “Freedom has to come from within,” he says. Then he turns to Wyrick: “You can see I haven’t changed much.”

“I didn’t expect you to,” Wyrick says genially.

“If I needed surgery, I’d think small and let Chris do it,” Wyrick says to a visitor. After Coppola and the residents have left the office, Wyrick elaborates: “He’s probably one of the best surgeons I’ve ever seen in terms of technical skill, knowledge, and compassion. A lot of surgeons can put the first two together, but it’s hard to get all three.” He pauses. “Sometimes I have a hard time imagining Chris is still doing surgery, because I can’t imagine how many guys could do the same thing day in and day out and put that much effort and that much passion into it and not get callous, and not get cynical, and still approach every day like it’s a gift of God, and every patient in that way.”

After Coppola returned to Texas, Meredith compiled his e-mails, wrote a foreword, and published the collection as a book, Made a Difference for That One: A Surgeon’s Letters Home from Iraq (www.iuniverse.com). The couple has sold about 1,000 copies and donated $850 in profits to support the Fisher House Foundation (www.fisherhouse.org), which funds a network of houses where families can stay when visiting a hospitalized military relative. “Opening up these homes for injured soldiers’ families,” Coppola says, “is a whole lot better way of showing your support for the troops than putting a yellow ribbon on your car.”

Nowadays, when Coppola sees men and women who have fought in Iraq, he says he’s happy to see them alive: “As a representative of all who served, I’m relieved that they survived. It makes me proud because of what we can do to keep more of the injured troops alive than in past wars. “

Still, Coppola is counting the days until he can leave the Air Force. “I really don’t believe in the vision of the corporation,” he says of the military, “to enact the political decisions of the administration.” On his laptop he keeps a computer program called the Donut of Despair. Handed from one military person to another, it’s a customized pie chart showing time served and time remaining, in days, hours, minutes and seconds. Until he’s out, though, Coppola says, “I feel wholeheartedly that it is my duty to go over and take care of our soldiers. If they’re over there risking their lives, getting shot, it’s my job to be there taking care of them.”

He still thinks about Marien. He’s heard that, a month after her death, her father was shot and killed. He notes that her little sister would now be the age Marien was when she arrived in his operating room.

Perhaps the most difficult task for a pediatric surgeon is to tell parents that their child has died. Coppola copes with this by retreating to a hallway or stairwell beforehand to recite a comforting poem to himself. Sometimes it’s the quotation from Emerson that’s carved on Soldier’s Memorial Gate at Lincoln Field:

’Tis man’s perdition to be safe

When for the truth he ought to die.

Chris Coppola is scheduled to return to Iraq this fall.

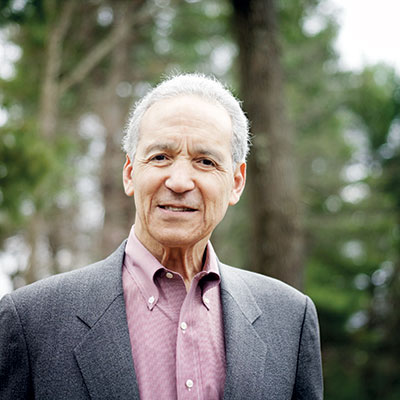

Augustus A. White III ’57

The Vietnam War was escalating in 1966 when Gus White ’57 got the word from his draft board in Memphis. He’d be drafted in a few months, as soon as he finished his surgery residency at Yale. As the only son of a widowed mother, the thirty-year-old White faced a sobering decision. He could probably avoid going to war if he volunteered for the air force, the reserves, the national guard, or the public health service. But after a long internal debate, he chose the most dangerous option: joining the U.S. Army Medical Corps. For an orthopaedic surgeon, it was a ticket to Vietnam.

White came up with various reasons for going. He felt a debt to those who had fought to defeat the Nazi regime in World War II. He also reasoned that in the medical corps he would be saving lives, and after nine years of studying and training, he looked forward to using his surgical skills intensively. “There would be no place in the world where there would be a better opportunity or a greater need,” says White, who is now a professor at Harvard Medical School. “I was like a racehorse, ready to get out of the starting blocks.”

White arrived in Vietnam in August 1966. He was stationed at the 85th Evacuation Hospital at Qui Nhon, on the coast 250 miles northeast of Saigon. When casualties rose, the camouflaged helicopters arrived again and again, and White and his colleagues might work thirty-six or even forty-eight hours straight. “It was like sitting beside a river of blood,” White wrote in a diary he kept during his year in Vietnam.

A Quonset hut with a corrugated metal roof served as the triage building. Corpsmen who met the helicopters would rush in carrying stretchers, setting each one down on a pair of sawhorses. In the first hectic moments after patients arrived, nurses and doctors would toss bloody sponges, feces, mud, and body parts into the metal bucket beside each stretcher, simultaneously checking for breathing and bleeding. Those closest to death went to the operating room first. “Your hands to some degree get on automatic pilot,” White says.

One day White discovered the limitations of automatic pilot. He was tending a young American hit by a rocket. “His leg was three times the normal size,” White says. “He said ‘Doc, am I going to make it?’ And I said, ‘Sure, you’re okay. You’ll be fine,’ and I got back to the leg. And he didn’t make it. I realized you can’t just pay attention to the leg. You can’t ignore the human being, because this may be the last time this person interacts with another human being.”

White noticed that a disproportionate number of the wounded were black—like him. Although African-Americans composed 11 percent of the U.S. population in the mid-1960s, roughly 20 percent of Americans dying in combat were black. White wrote in his diary: “The brothers have informed me of the inordinate frequency with which they were chosen as ‘point men.’ ” (The defense department would eventually correct the imbalance.) Even at the hospital in Qui Nhon, White says, “There was a lot of resentment from white males having a surgical peer who was black.”

This was familiar territory. At Brown, after White joined Delta Upsilon as its first black member, the chapter received a formal censure for this “unfraternal act.” When his fraternity brothers elected White and another student to represent them at the national convention in 1956, the fraternity cancelled the convention. (In the 1970s, the national fraternity acknowledged what it had done, contributed to a diversity scholarship at Brown as a form of restitution, and later named its achievement award in medicine after White.) White was the first African American to graduate from Stanford Medical School, the first to do a residency at Presbyterian Medical Center in San Francisco, and the first to enter the surgery residency at Yale.

Of the thirty physicians at Qui Nhon, White was one of two African Americans. He considered beforehand how he would present himself. Striking the right note would be a bit trickier in the army than it had been during his Yale residency, because in Vietnam he would be captain of his operating room.

White decided to heed an aphorism he’d heard: “If there’s no music, you don’t shuffle.” He would be direct with instructions or corrections—not arrogant, but not apologetic, either. Several months into his tour, six of White’s colleagues went to complain about White to their commanding officer, Major John A. Feagin Jr., also a surgeon. Feagin still remembers what they said: we don’t like Gus White dating our white nurses. “I said I thought the armed forces had integrated in 1945,” Feagin recalls answering. “I was disdainful.” Feagin was also annoyed that they would create divisions when teamwork was indispensable.

Feagin considered whether he should tell White what had happened. “I decided he had the right to know what people were saying about him. It wasn’t a matter of counseling, because he was free to choose. He was single, and [the nurses] were single,” he told White.

“I was angry, but I wasn’t surprised,” White recalls. He had held off from dating for the first few months while he decided how to behave. “I had thought this out a lot: ‘Are you going to do this in a setting where it’s so visible? Supposedly you’re over here fighting for freedom. You’re a free man.’ I’m talking to myself. ‘If you have freedom and you don’t exercise it, you might as well not have it.’ I’d concluded it was an ordinary, natural, appropriate thing to do, and so I decided to do it.”

No one confronted White about his social life again, but he made one concession: he stopped bringing dates to the officer’s club, reasoning that resentful men drinking liquor and carrying .45s might pose a danger.

The violence of battle grieved White, and he began taking pictures of wounded soldiers. He planned to send the gruesome photographs to President Lyndon Johnson, along with a letter delineating the realities of war. He told Feagin: “I’m going to be very respectful, but I’m going to tell him.”

Feagin cautioned White against the plan, but White persisted. “It’s respectful,” White remembers explaining. “It’s just freedom of speech.” Feagin reminded White that the army has protocols: the letter would have to travel up through the long chain of command—starting with him. “That would give us recognition that we don’t need,” Feagin recalls telling White. White gave up the idea.

One day White treated a nineteen-year-old soldier with terrible wounds. To White’s surprise, the young man cried because he wouldn’t be allowed to return to combat. “We should not really ever be surprised by what happens in wars,” White wrote in his diary that night. “The troopers would talk about fire fights with the enemy and close hand-to-hand combat like they would an important high school football or basketball game.”

White got a break from the turmoil most Saturdays. He and Feagin and a nurse would visit the St. Francis leprosarium seven miles from the hospital. Catholic nuns from Europe and Vietnam ran the community of 1,500 men, women, and children. The nuns wore ankle-length white habits and lived in a tranquil beachfront village built of pastel-colored marble found on the site. “It was a wonderful thing,” White recalls, “to leave all that blood and gore and stink and destruction in the town and to drive over the hill and enter this marble-laden community that looked like the set of a Walt Disney movie.”

White and his colleagues reconstructed tendons in the legs and ankles of some of the lepers. Sometimes they amputated a finger or part of a foot destroyed by the disease or by the unwitting damage people caused to themselves because they had no sensation in their feet and hands. The nuns fed the visitors memorable meals, a fusion of Vietnamese and French cuisine. White’s favorite dish was banana fritters that tasted of pineapple.

The outings raised his spirits. “As the Dalai Lama says, ‘How do you be happy?’ You’re happy by helping others. We helped the soldiers, certainly. This was somehow more peaceful, more gratifying, less frustrating. It’s better to fight natural disease than man-made trauma. I think all doctors have to some degree this missionary desire to go work somewhere where medical care is really needed, and to give it.”

White also treated Viet Cong hurt in battle and brought in by the American medics both as a humanitarian gesture and because prisoners might serve as pawns. Enemy fighters got the same treatment as Americans and South Vietnamese. At first, White felt a little sorry for the Viet Cong, who were known among the soldiers as Charlie. “I don’t fully understand what motivates Charlie,” White wrote in his diary a few weeks after arriving. “He couldn’t possibly expect to win. He should be convinced that we’re not going to withdraw. Well, maybe he’ll give up.”

Within a few months, White had begun to see Charlie differently. In February he wrote in his diary about a discussion he’d had with a Vietnamese civilian who had been wounded after picking up an AK-47 to fight the Americans. In his diary, White describes that conversation as “one of the most intense, interesting, and authentic educational experiences of my entire sojourn in this forsaken land.” The man was a young French-educated math teacher who spoke English. He did not favor communism, but he called the Americans invaders, intruders no more welcome than the French who had colonized the country for almost a century before the Vietnamese routed them in 1954. White recorded the man’s words: “You people are the aggressors. We’re just trying to liberate our country.… We will win, because the great majority of the people support us.… You’re here fighting merely to save face and win a politically strategic point.… We are each fighting for survival. We are at the bottom and have no way to go but up. This fact gives us much patience and makes us hard fighters who take big risks and frequently surprise you.”

“Forty years later,” White says, “the crisp academic synopsis is the same thing this fellow told me. The regimes we supported in South Vietnam didn’t represent the people. They [the South Vietnamese government] appreciated us because we were keeping them in power.” But for most Vietnamese, the war against the Americans was a war of liberation.

Feagin remembers keeping a statue of Ho Chi Minh in the office he shared with White. If anyone questioned him about the statue, Feagin would reply: “He’s a freedom fighter, too. He’s a liberator. He believes in his people.” White doesn’t remember the statue, but he says that although he opposed communism, “I respected Ho Chi Minh for his courage and his leadership.”

After serving his year in Vietnam and another year in the army in California, White earned a PhD at Karolinska Institute in Stockholm. There he met his wife-to-be, Anita Ottemo. He also began work that provided the foundation for his book, The Clinical Biomechanics of the Spine, written with mechanical engineer Manohar M. Panjabi. The book established White as a leader in his field. He worked and taught at Yale for nine years, then joined the Harvard faculty in 1978. He collected a list of honors that takes up two pages of his C.V., among them the Bronze Star for his service in Vietnam, six years as a Brown trustee, and the Diversity Award of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons.

White was on the Brown campus to receive an honorary doctorate during Commencement 1997 when, at a symposium on the Vietnam War, he heard mention of a forthcoming conference on the war to be held in Vietnam. Its purpose was to look for lessons in the failures of the war. White got permission to go as an observer. Among those attending were political leaders including Robert McNamara, secretary of defense from 1961 to 1968; Vietnamese and American generals; and scholars from both countries. This time, White flew to Hanoi.

White thinks the Vietnam War resulted partly from the ethnocentrism of white males. “The whole society is on automatic pilot giving privilege to, giving opportunities to white males, 24/7. That skews your vision. The world is different without that privilege.” If less-privileged Americans had contributed to foreign policy, they would have had an “outsider’s view.” They might have been able to understand how the Vietnamese saw their situation. (White concedes that Condoleezza Rice’s current role undermines his theory.)

White’s grounding in the “cultural competency” that might prevent or resolve conflict comes in part frorm his work in medicine. He has studied how the quality of health care is eroded by culturally based misunderstandings: false assumptions, poor communication, stereotyping, and jumping to conclusions. Groups that suffer include the obese, the poor, women, racial and ethnic minorities, members of some religions, prisoners, and anyone who is not heterosexual.

White is writing an autobiography, in part about his year in Vietnam. Because of his experience, “when I meet any kind of veteran, I say thank you—the same way I thank schoolteachers.” As for policymakers, White says, “Every leader should spend a day with a military surgeon or a nurse—a day in a military hospital. You wouldn’t have to say a word to them.”

Cathy Shufro is a writer in New Haven, Connecticut.