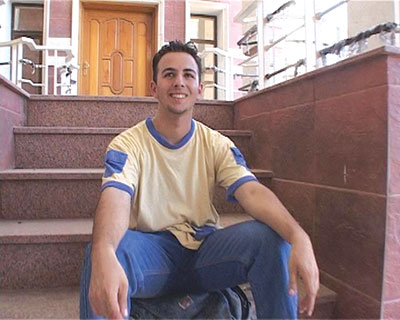

“You can join a band, or you can join a militia,” says Adel, a twenty-three-year-old engineering student at the University of Baghdad as he straps on an electric guitar. “Playing this live music and screaming, it’s like a therapy,” he says, flashing a gap-toothed grin toward a video camera.

Adel is one of three Iraqi students who are chronicling their lives on HometownBaghdad.com, a series of documentary videos produced and distributed by Michael DiBenedetto ’03. In addition to the movie-star-handsome Adel, the cast includes medical student Ausama, and Saif, who wants to become a dentist.

Hometown Baghdad made its debut on the Web on March 19, the fourth anniversary of the start of the Iraq war. New episodes are posted every few days, first to Salon.com, where they appear exclusively for twenty-four hours, then to YouTube and other sites. The “webisodes” range from forty seconds to five minutes.

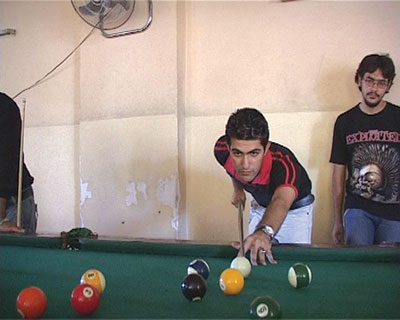

Some are funny, some poignant, some banal. In one episode, Saif and his friends hang out, watching soccer and playing guitar while they prepare to say goodbye to a friend leaving for Jordan. In another, Ausama turns the camera on his young cousins as they describe a man they saw on their way home from school; he’d been shot in the head, and his brains spilled onto the road. Then the boys race around the house firing imaginary guns at each other and laughing goofily.

In an episode called “Hidden Camera,” Adel hides his video camera in a bag with a hole cut into it so he can film the wreckage and garbage in his neighborhood. “I’ll try to be careful and not say anything in English,” he says before leaving the house. If he’s caught with the camera, he says, “They’ll kill me!”

He says this in a singsong voice, but he’s dead serious. “The Iraqi producers risked their lives to do this,” says DiBenedetto. “The cast members put themselves in a ridiculous amount of danger.”

Hometown Baghdad was originally conceived for television. DiBenedetto works for NextNext Entertainment, a Manhattan-based media production company whose subsidiary Chat the Planet had produced an extraordinarily successful series of TV specials linking young people around the world. In early 2006, DiBenedetto and a colleague headed for Los Angeles to pitch a Baghdad-based reality-TV series to cable networks.

Then the urgency of life in Iraq persuaded DiBenedetto and his colleagues to use the Internet instead. They learned that their Iraqi filmmakers and cast “were receiving death threats and thinking about leaving Baghdad,” says DiBenedetto. Deciding not to wait for television’s snail’s pace, the producers went to two of their most reliable funders—the Shei’rah Foundation and Cinereach—and said, “Listen, we really want to tell these stories. We don’t really know what it’s going to look like. We don’t even know who is going to leave halfway through our production, but we need to start shooting,” says DiBenedetto.

The funders agreed, and in June the Iraqi team began filming, sending 120 hours of tape to NextNext’s New York offices for editing. The documentary will ultimately comprise forty-some episodes, upwards of two hours of programming.

Using the Web allowed the producers to connect viewers in ways TV could not, says DiBenedetto. “Online video has such an amazing ability to generate dialogue and real engagement,” he says. “There’s so much sharing with blogs that if it catches on, it will immediately spread.” So far, the Hometown Baghdad blog has received about 4,000 hits a day. Some episodes have been viewed as many as 10,000 times on YouTube. Online giants like BoingBoing, DailyKos, and Huffington Post have been spreading the word, and in the first week of the series the blog search engine Technorati registered more than 150 blogs linking to hometownbaghdad.com.

DiBenedetto, who says he “lives his life online,” is a passionate believer in the power of the Internet to connect everyday people and thus to humanize the war in Iraq, which is his ultimate goal. “People deserve to hear these stories,” he says. “ It may change the way that they see the whole war and the whole world.”

Beth Schwartzapfel is a BAM contributing editor.