On the College Green stands a flagpole. History buff Joseph Dowling '47, now an emeritus professor of ophthalmology, likes to ask his colleagues if they know whom it commemorates. No one he's asked has ever answered correctly. The inscription on the flagpole's marble-and-bronze base tells part of the story: "Samuel Gridley Howe, Class of 1821, for his service as a surgeon in the Greek War of Independence." But it barely hints at the breadth of Howe's accomplishments or the scope of his influence. Samuel Gridley Howe has enough historical firsts and foundings attached to his name to fulfill the ambitions of ten men - a good thing, since he also had the ego of ten. His life's goal was to make a great contribution to the intellectual and reform movements of his day. Many of his ideas were more than a century ahead of his time, and educators and social workers are only now appreciating the importance of others.

"I consider him the greatest social reformer of the nineteenth century, bar none," Dowling says. "He was into everything - mental health, prison reform, abolition of slavery, educating the blind, the deaf, and the deaf-blind." Howe set the course for what later became known as disabled rights and special education, although he would have despised those terms as much as he did the terms of his own day. A century before the concept of "inclusion" was coined, he argued that people with disabilities should live, learn, and work among their families and communities, to the benefit of all.

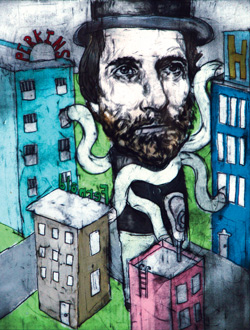

Howe founded the first U.S. schools for the blind and for the mentally retarded, the institutions today known as the Perkins School for the Blind in Watertown, Massachusetts, and the Fernald State School in nearby Waltham. He was the first to teach language to a deaf-blind person, a seven-year-old scarlet-fever survivor named Laura Bridgman - an achievement that made both teacher and student world famous. Even as Howe pioneered the creation of schools for the disabled, he was prescient enough to foresee and condemn the dependence they fostered - what is now known as institutionalization.

Howe came of age in the full blaze of the reform movement called the New England Renaissance, and lived in Boston, its center. He was among the intellectual giants of the era, and two of his closest friends are well remembered as such: schools across the nation are named for educator Horace Mann, class of 1819, and Boston traffic reporters regularly utter the name of abolitionist congressman Charles Sumner, after whom one of the city's traffic-clogged tunnels is named. Samuel Gridley Howe and his wife, Julia Ward Howe, were also leaders in the abolitionist movement. Today his role is largely forgotten, while she is immortalized as the poet who wrote the abolitionist anthem, "Battle Hymn of the Republic." Still, Howe, whose accomplishments exceeded all of his peers', failed to achieve name recognition beyond his own lifetime.

At Brown, Samuel Gridley Howe distinguished himself more as a troublemaker than as a student. That he attended college at all was serendipitous. In the economic downturn following the War of 1812, Howe's father, a Boston rope merchant who supplied ships, could afford to send only one of his three sons to college. So Joseph Howe took down the big leather-bound family Bible from the mantle and asked each boy to read a chapter, as a way of determining who had the best scholastic aptitude. Samuel, the youngest, was clearly the best reader. Harvard was the closest college, but it was infested with Federalists, and Joseph Howe, a Democrat in the vein of Thomas Jefferson, did not want his son there. Instead he selected Brown College.

Young Samuel craved adventure more than education. So he made his own excitement. "What I like about him is he made so much trouble. He was so entertaining," says Martha Mitchell, the retired John Hay Library archivist and author of the Encyclopedia Brunoniana.

His perpetual pranks - putting ashes in a tutor's bed, squirting ink through a keyhole at a tutor checking on him - earned him several sentences of "rustication," being sent to a minister's home in the country for months at a time to study without distraction. One darkly overcast night, just back from one of his solitary confinements, the young Howe led President Asa Messer's horse, Caesar, up to the belfry of University Hall, first padding the elderly animal's hooves.

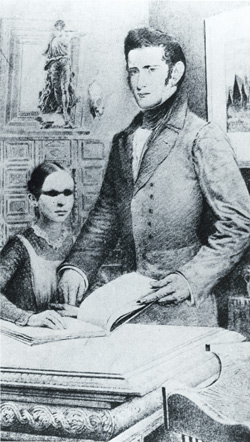

Leaving the scene, Howe was spotted by a tutor - Horace Mann. He agreed not to report Howe, if he would get the horse back down, quickly and quietly. Thus began a lifelong friendship. Mann, always the serious scholar, had already decided his life's goal was to work for a free education for all. The two men would be closely allied throughout their lives - obtaining state funding to educate teachers, devising a way to teach deaf children to speak, and constantly advising each other on their many crusades. As middle-aged men, they took their new brides on a yearlong European honeymoon together.

Anna Shaw Greene called him "the handsomest man I ever saw" in the biography written by Howe's daughter Laura E. Richards. "When he rode down Beacon Street on his black horse, with the embroidered crimson saddlecloth, all the girls ran to their windows to look after him," Greene recalled. Richards herself commented, "There was a power in him, a look of untiring, unresting energy, which drew all eyes. His presence was like the flash of a sword."

After college, Howe studied medicine at Harvard and then, following in the footsteps of his hero Lord Byron, set off to Greece to aid in its revolution against Turkish rule. But in the months after his Greek adventure, the twenty-nine-year-old Howe was adrift and depressed, and still searching for a way to make a name for himself.

John Dix Fisher, class of 1820, provided the spark. Like Howe, Fisher had continued from Brown to Harvard Medical School, and then on to Europe. In Paris, Fisher had visited the world's first school for blind children, L'Institution National des Jeunes Aveugles, which had been founded in 1784. He was amazed. Americans at the time generally believed that people with disabilities should be shut away in asylums or, at best, kept at home as objects of charity. Some even said the most compassionate policy was to keep them from learning, so they would not know what they were missing. In France, however, blind children were taught to read and write raised type. They learned mathematics, geography, languages, music, and manual arts.

Returning to Massachusetts, Fisher persuaded a small group of family and friends, including Horace Mann, to incorporate the New England Asylum for the Blind. The Massachusetts legislature allocated $5,000 to the new school without knowing anything about how it would work or even how many blind children lived in the state. Fisher set about finding a director, but a string of candidates turned him down.

With no building, teachers, students, and, perhaps most important, no director to make things happen, little did. Then, in the summer of 1831, Fisher spent a day riding with his college friend Howe, lamenting his predicament. Howe volunteered for the job.

Howe set off for Europe again, this time to see how the schools there worked. Where Fisher had been amazed that blind children could be taught at all, Howe saw ways to do it better. He called Europe's schools for the blind "beacons to warn rather than lights to guide." His critique, the first of the many voluminous reports he wrote for the school's trustees, remains a foundation for special education today.

Howe disapproved of teachers and family members always stepping in to help and protect blind children. He believed such children should be taught both academics and the skills to support themselves according to individual aptitude - just like other children.

He made daily outdoor exercise mandatory, including ocean swimming. Students later wrote of shivering during the required hour on the wintry waterfront at the school's South Boston location.

He believed the children should learn proper social conduct, and envisioned a special place for music. The early schedule included four hours of music lessons and practice daily, and by the end of Howe's directorship, five of the eleven teachers taught music. For decades, blind children were mainly encouraged to become piano tuners or church organists - the latter was how Louis Braille was known in France during his lifetime.

The school grew rapidly, outgrowing several locations in Boston. Howe directed it for more then four decades, until his death in 1876. But his attention was constantly drawn to other causes. During his frequent absences, the reliable Fisher, who served as the school's doctor and vice president, often stepped in.

As incomprehensible as the idea of educating children with physical disabilities was to nineteenth-century Americans, the idea of teaching "idiots" (the common term for persons with any mental disability) was even more outlandish. Mentally disabled people were considered paupers and sent to poorhouses or prisons.

Howe insisted that children with mental disabilities could be taught language as well as the skills to support themselves. It was being done in Europe. In 1848 he persuaded the state legislature to fund an educational experiment with ten children at Perkins.

These ideas made Howe a public laughingstock, even among his friends. One said his ideas were "for idiots as well as concerning them." But Howe relished standing up to his detractors - and proving them wrong. At the end of two years, each child had improved in health, behavior, language, and personal skills. In 1856 he became superintendent, without pay, of the Massachusetts School for Idiots and Feeble-Minded Youth, which was built close to the Perkins school in South Boston.

Howe's greatest contribution to society, however, surpassed the sum of all these individual reforms. Argumentative, self-righteous, and highly energetic, he had the passion to confront societal attitudes he saw as wrong - all of them - and the tenacity to keep doing it for half a century. He set in motion debates that are still going on. And no matter how foolish it made him look, he vociferously opposed any idea he viewed as incorrect, whether it was common wisdom or his own previous pronouncement.

In 1866, for example, he was asked to speak at the cornerstone laying for the New York Institution for the Blind in Batavia, New York. He was at the pinnacle of his career, famous as the person who had brought institutions for disabled people to the United States. For years he had traveled across the country with his students in tow to demonstrate what they had learned. He had persuaded numerous states, including Ohio, Virginia, and Kentucky, to start their own schools.

His New York hosts were shocked therefore to hear Howe suddenly renounce these existing institutions as evil. (See "The Evil of Asylums," above.) He accused schools of taking in pupils indiscriminately to increase funds and of making students dependent, "creating the necessity, or the demand, for permanent life asylums." Questioning the wisdom of opening another "great showy building, and gather[ing] within its walls a crowd of persons of like condition or infirmity," Howe urged his colleagues to establish as few institutions as possible, to shut down as many as possible, to keep those that could not be closed as small as possible, to turn away all students who could be taught in the common schools, and to return students to their families and communities as soon as possible.

Howe's remarks appear ironic, even hypocritical, in light of his career. His own prize student, Laura Bridgman, remained at Perkins until her death, never again comfortable living with her family and certainly not out in the world. But his criticisms proved valid, and the conditions he warned against in his Batavia speech got worse - much, much worse - before they got better, especially for the mentally retarded. Over the next century the size and number of institutions multiplied across the country. People with disabilities were isolated from the rest of society as never before. Leaders of institutions campaigned for families to turn over their disabled children, often limiting family visits. By the middle of the twentieth century, investigative journalists and parent groups had uncovered horrific abuses - radiation experiments on clients, sterilization, overmedication, forced labor with minimal or no pay, overcrowding, poor food and sanitation, freezing and overheated temperatures, and widespread mistreatment.

"What Howe's work led to was not what he had intended," says Larry Tummino '70, assistant commissioner for the Massachusetts Department of Mental Retardation, which is now in the process of closing the Fernald School. "Howe believed people with disabilities and mental retardation could learn and be productive and be part of society. What was missing was good training. But what he started turned into something bleak. People were underestimated, overlooked, and made into social pariahs."

In the early 1970s Tummino became part of a new generation of human-services workers who embraced an ideology called normalization, which in part argued for the right of disabled people to community living. Howe has become a hero to this cadre. Massachusetts has closed three of its eight institutions for the mentally retarded, and ten other states have closed all their institutions. Increasingly, state mental-retardation budgets are being allocated for services that enable clients to live and work in their communities.

"We're finally getting back to what Howe said in that speech," Tummino says, "treating people humanely and looking at their gifts, not just their deficits."

So how did Samuel Gridley Howe, who wanted fame so much, achieved so much, and left such a forward-thinking legacy, fall into obscurity?

For one thing, he was upstaged by three powerful women. Ironically for Howe, he is best known today as the husband of poet Julia Ward Howe. As ambitious as he was for himself, and as zealous on behalf of the oppressed, he was determined to keep his smart, talented wife at home with their six children. Against his will, she kept on writing and speaking publicly. Julia became a prominent women's rights and peace activist, founding Mother's Day as a day for women to demand peace.

Fifty years after Howe's breakthrough with the deaf-blind Bridgman, a feisty Perkins valedictorian named Annie Sullivan pored over his extensive reports to prepare for her first job - as governess to an uncontrollable Alabama girl named Helen Keller. The charisma of these two young women quickly eclipsed Howe's and Bridgman's historical first.

When history has remembered Howe, it has sometimes been unkind - and deservedly so. Blind readers decry that the United States was the last developed country to adopt the simpler six-dot Braille alphabet in 1918, in part because of Howe's insistence on his own Boston Line Type. The deaf community has vilified Howe, along with Alexander Graham Bell and Horace Mann, for opposing the use of sign language. Elisabeth Gitter's 2001 The Imprisoned Guest portrays Howe as a patronizing Victorian who gained Laura Bridgman's trust to glorify himself, then abandoned her to the institution he had built. "His interest in the blind, the deaf, and the retarded doesn't resonate with people today, the way women's suffrage and abolition do," observes William Wyatt, retired chair of the classics department. "He was an exemplary figure, but he was always working for people that most of us don't want to think about."

That may be the most bitter historical irony for Howe: He spent his life raising questions that go to the heart of our humanity - how we treat anyone considered different - and fiercely championing a constituency that the public would rather forget. And for that he, too, has been forgotten.