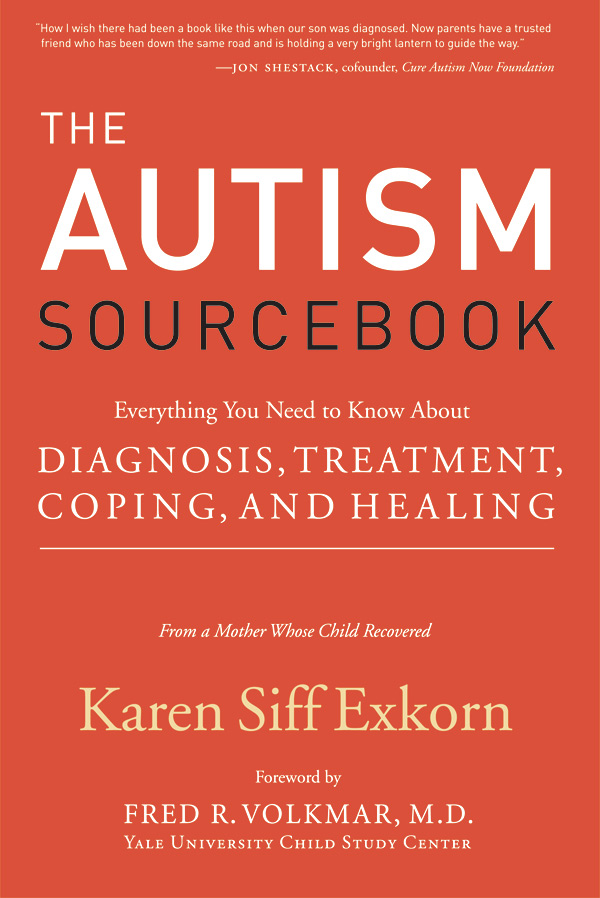

The Autism Sourcebook: Everything You Need to Know About Diagnosis, Treatment, Coping, and Healing by Karen Siff Exkorn '82 (Harper Collins); and Help for the Child with Asperger's Syndrome by Gretchen Mertz '81 MAT(Jessica Kingsley Publishers).

Karen Siff Exkorn's son, Jake, was two years old when he lay face down in the driveway, cheek pressed into the gravel, at his own birthday party. For his mother it was the last straw. After six months of reassurances from the pediatrician ("He's being obstinate"; "Boys develop slower than girls"; "Don't worry"), Siff Exkorn took matters into her own hands, scheduling an appointment with a developmental specialist.

Karen Siff Exkorn's son, Jake, was two years old when he lay face down in the driveway, cheek pressed into the gravel, at his own birthday party. For his mother it was the last straw. After six months of reassurances from the pediatrician ("He's being obstinate"; "Boys develop slower than girls"; "Don't worry"), Siff Exkorn took matters into her own hands, scheduling an appointment with a developmental specialist.

"Autism," he said. With that one word, he ushered Siff Exkorn and her husband down a rabbit hole.

Suddenly Siff Exkorn was investigating the developmental trajectory of kids with Jake's diagnosis, learning which interventions researchers favored, and advocating for her son's treatment - all while trying to maintain some modicum of family life. "It was, in essence, as if I was running a business," says Siff Ex?korn, who abandoned her management consulting firm to coordinate Jake's care. "While other kids were going to the playground, taking music classes, and napping, Jake was in one-on-one therapy. We also did speech therapy, a special diet, and other alternative treatments. My two-year-old had the equivalent of a full-time job."

Close to 1.5 million people in the United States have been diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder, a congenital neurological condition that affects communication, fine motor skills, and socialization. In recent decades, rates have spiked - from one in 2,000 in the late 1960s to one in 500 or higher, depending on the source. The explanation isn't medical; it's social, says Rowland Barrett, an associate professor of psychiatry and human behavior at the Brown Medical School. "Parents have become more aware, professionals have become more aware, and post-1990 there was a major change in public policy," he says, referring to legislation that made children with autism eligible for state and federally funded special education.

Awareness increased further when the 1994 edition of the DSM-IV guide to psychiatric diagnoses added Asperger's syndrome to the high-functioning end of the autism spectrum. "It's an epidemic of recognition," says Barrett, who runs the developmental disabilities program at Bradley Hospital, a children's psychiatric facility in East Providence. "It's a broadening of methodology and increasing awareness."

After watching thousands of families cope with autism, Barrett says the most successful build alliances - with educators, health care providers, and other families. "They're almost like lawyers, in terms of being good consumers of services," Barrett says. "They're aware of their rights and they advocate. They're not afraid to ask questions, they belong to support groups, and they can separate the fads from science. They don't put themselves out on an island."

Siff Exkorn offers those families with autistic chilren a comprehensive resource. The Autism Sourcebook is a 400-page reference on everything from understanding an autistic child's behaviors to explanations of available treatments and advice for dealing with sibling and spouse relationships. "It's the book I wish I'd had when Jake was diagnosed," says the author, who incorporates anecdotes from her own family's experiences. "There was a lot of information out there, but it was all over the place. I wanted one book that could tell me everything from A to Z - from how to help him to how to cope emotionally."

As Siff Exkorn coordinated medical and educational interventions for her son in the New York City suburbs, paralegal Gretchen Mertz and her husband were doing the same in Philadelphia. Five years after their son was diagnosed with Asperger's, Mertz authored Help for the Child with Asperger's Syndrome. Mertz focuses more narrowly on navigating the social service maze, explaining diagnoses and detailing the financial and educational implications for each, describing how to work with the school system, and suggesting strategies for coordinating services. "There's a feeling of desperation when you're trying to pull it all together," she says. "You don't know what your child could do if they got enough help."

Both Mertz and Siff Exkorn have seen significant improvement in their sons' abilities; both boys attend mainstream classrooms with minimal intervention from aides or therapists. HarperCollins even promotes Siff Exkorn's book with the upbeat cover line "From a Mother Whose Child Recovered."

Still, Brown psychologist Barrett offers a word of caution. "Autism spectrum disorders are lifelong, serious developmental disorders, and there is no cure," he says. While nearly a quarter of autistic children move into mainstream classes as they respond to early, intensive interventions, half show little improvement. Furthermore, he says, autistic children retain tendencies that may affect them later in life - when social de?mands at school increase, for example, or at times of stress.

"The assumption," Barrett says, "is that because such children become indistinguishable to the naive observer, they're cured and life will go on normally for them, that they'll be on the normal developmental trajectory for the rest of their life. Our experience is that that's not necessarily so."

Sharon Tregaskis is a freelance writer in Ithaca, New York.