Copycats abound in the history of painting, from Rubens, who obsessively copied Titian as a way to learn the master’s secrets, to nameless forgers looking to make a quick buck. With his series of bootlegged paintings by contemporary artists, Eric Doeringer ’96 cheekily works the murky space in between.

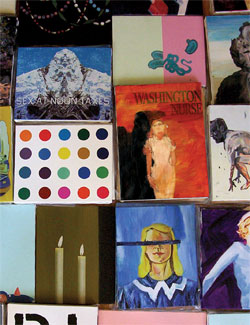

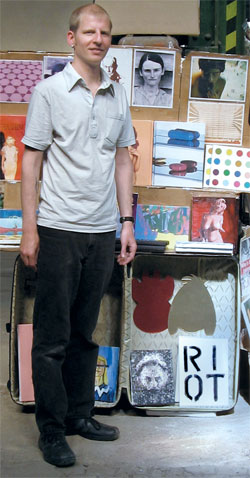

On a recent afternoon the rangy blond painter stood in his Brooklyn studio and gestured at an array of small, bright canvases hung on a patch of wall between two long windows. Among them were scaled-down reproductions of a Jenny Saville nude, a portrait by John Currin, and a grid of multicolored polka dots by Damien Hirst. He sells these and more than 100 other knockoffs for between $60 and $200 on sidewalks outside art fairs, museums, and galleries in the United States and Europe, in what has become a thriving business.

The irony is that it was just that business he set out to critique. Doeringer studied painting at Brown but by his senior year had become less interested in Art with a capital “A” than in the economics of the art market. “A painting has no inherent value,” he says. “It’s not made of gold or precious stones. It’s worth what people are willing to pay for it.” At the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, from which Doeringer received an MFA in 1999, he grafted his own image onto commercially available products, such as a gnomish paperweight and a pack of trading cards, and called them self-portraits.

Doeringer envisioned the Bootleg Project, as he calls his line of reproductions, as a one time performance that would spoof both the notion of originality and the received wisdom that an artist should not get his hands dirty in the actual business of selling paintings. “As an artist, it’s sort of looked down upon to sell your art in the street,” he says—so that’s exactly what he did, right outside some of Chelsea’s hottest galleries. Because he had paintings left over, he came the next week, and the next, eventually building a loyal following.

And making a few enemies. In November one gallery owner lodged a complaint with the police about unlicensed street vendors in the area. Doeringer had to pack up and leave, but a week later he got revenge when the New York Times described the incident as a classic David-and-Goliath story, the witty young entrepreneur whom everybody loves going up against the crass, clueless businessman who doesn’t get the joke.

After the Times article appeared, a tide of orders came in, including one for a full set of all 100 bootlegs. And this spring Doeringer is back in Chelsea—with a license. But there’s a chance that his growing celebrity could hurt. After the Chelsea incident, John Currin, one of Doeringer’s best sellers, and a handful of other artists asked Doeringer to stop copying their work. (For now, he has decided to comply rather than risk a lawsuit.) What’s more, he has had to raise his prices. It seems that some gallery owners are now selling his work—and taking a cut for themselves.